Spectrum Culture has a fun new feature that compares and contrasts remakes of films with their original versions. It's already made for some great reads, and I finally got around to writing an entry of my own. For my piece, I stacked Joseph Sargent's 1974 The Taking of Pelham One Two Three against Tony Scott's 2009 remake. I found both to be fantastic pieces of popular entertainment, one an unpretentious thriller that embodies mid-'70s ennui and grime, the other a frenetic, color-soaked reflection of post-9/11 and post-2008-crash America. Both are smarter than they seem, though Scott's film is a bit more eager for you to know it. A rare case of two totally valid interpretations of the same root material.

My full piece is up now at Spectrum Culture.

|

|

|

|

|

Home » Archives for April 2012

Monday, April 30

Saturday, April 28

Geoff Dyer — Zona: A Book About a Film About a Journey to a Room

I mentioned reading this a few weeks back and that a full review was on the way. It's finally up at Spectrum Culture. Zona was a great read, illuminating in its anecdotal production details but best for Dyer's beautiful, sometimes poignant thoughts on one of the greatest of all films. There are some hiccups and digressions that grate, but for the most part this is one of the best books on a single movie I've yet read. Highly recommended.

Check out my full review now at Spectrum Culture.

Check out my full review now at Spectrum Culture.

Friday, April 27

Spirit - Stallion of the Cimarron: Dialog Writing

A. This movie is about Spirit, a wild mustang. Watch the segments and, in small groups, write down the dialog you imagine took place in the scenes. Imagine that the horses are speaking English! Use your imagination and be creative.

A. This movie is about Spirit, a wild mustang. Watch the segments and, in small groups, write down the dialog you imagine took place in the scenes. Imagine that the horses are speaking English! Use your imagination and be creative.*Note to the teacher:

Pause the segments when the slide of a heart shows up. Have the groups write down the dialogs, following the instructions for each part as shown below, before you play the next segments, and pause again on the heart slides.

Scene 1. Write down the dialog between Spirit and his mother.

Scene 2. Write down the dialog between Spirit and the other horses.

Scene 3. Write down the dialog between Spirit and the other horses.

Scene 4. Write down the final dialog between Spirit and his mother.

B. Now role play your dialogs, but you are people now, not horses. If possible, don't read the dialog, just act it out (if you prefer, you can be horses, not people, but the dialogs have to be in English, of course!!).

C. Extra Activity:

Write a short narrative/paragraph about the scene.

THERE IS NOT A WORKSHEET FOR THIS ACTIVITY FOR IT IS NOT NECESSARY FOR THE ACCOMPLISHMENT OF THE TASK

MOVIE SEGMENT DOWNLOAD - SPIRIT, STALLION OF THE CIMARRON

Monday, April 23

Day & Night (Teddy Newton, 2010)

[The following is an entry in Pussy Goes Grrr's Short Animation Blogathon, running April 23-27.]

My first experience with short animation was, naturally, old Looney Tunes cartoons played in syndication on morning TV when I was growing up in the '90s. Yet it was through Pixar that I first got the chance to see shorts (either animated or live-action) on a big screen. I still remember the first of Pixar's theatrically attached shorts—Gen's Game, the loopy back-and-forth of an old man ferociously playing himself at chess in a park—better than the feature it accompanied, A Bug's Life. Though I was far, far too young to elucidate how the short's construction hooked me, the way its cuts and "angles" made the old player seem like two distinct people each formulating secret strategies against the other was riotous and thrilling. For the longest time, the lingering, nostalgic giddiness Gen's Game produced made it my favorite of the Pixar shorts.

Until Day & Night. Released 12 years after 1998's Gen's Game, Day & Night was the first Pixar short since that one to be superior to the film it supported. The difference is that the earlier film easily stood out against Pixar's sophomore slump. But Day & Night, that was attached to one of the studio's finest, the unexpectedly poignant, technically superfluous Toy Story 3. At six minutes long, Day & Night proves as much a technical achievement as the feature presentation, and its driving theme as simple and direct yet illuminating and intelligent as the themes of maturation and moving on in Toy Story 3.

True to the time limitations of the form, the short sets itself up quickly. Opening on the usual Pixar 3D animation of an idyllic field, the camera pulls back until it reveals this world as being the tightly contained view of a transparent being existing in 2D space against an infinite black void. Stumbling about in his morning routine, this being happens across someone just like him. Well, almost. Instead of showing an area basked in the morning sun, this other creature offers a window into night. Startled, the two soon engage in a hostile pissing match to demonstrate their superiority, each showing off what goes on at their respective times to impress and cow the other.

The thematic implications are obvious, and only more so as the shortened plot swiftly moves the two from antagonism to mutual admiration and cooperation. Capped off with an old lecture from Wayne Dyer about the importance of embracing the different, Day & Night makes a clear, direct argument for children that warns against xenophobia and just generally hating the unknown. But what makes the film truly masterful is how it's put together. The movement of the two beings in the 2D realm, as well as their moods and expressions, is demonstrated through objects and sounds captured within their portal bodies. For example, when Day wakes up to a rooster crow at the start, thunderclouds communicate the cracking of stiff joints and the sigh of pleasure he emits when he walks into the releasing rush of a waterfall is...well, guess. Even better is the integration of the outer 2D space with the 3D textures within, enhancing the texture of both levels. For a more in-depth account of how this looked in a theater with 3D glasses on, I direct you to Tim Brayton's simply magnificent contemporary review of the short, which he later named the best film of 2010.

Tim's review is so incredible that I'll pretty much stop here, unable to equal his piece, much less add to it. Even his title, "Hegel for Wee Folk," is brilliant, though it also offers perhaps the one area where I can object to him on any grounds. Though the use of 2D and 3D to illustrate the conflict between day and night certainly highlights Hegelian dialectic in several respects, the film's final moments, of the dualities of the two creatures reversing, move beyond Hegel into something more reminiscent of Levinas. When the two stand side by side, the sun setting in one and rising in another (complete with a brief meeting of the two semicircles at the midpoint of both bodies), the self and other invert and become irrelevant, fictitious projections that compel us not into the hatred cautioned against by Dyer but in the fundamental need for empathy as espoused by Levinas. Whether it owes more to Hegel or Levinas, though, Day & Night still broaches at least one of the most challenging philosophers in history, even as it presents a cogent, easily parsed out message for kids. It's one of the best short films I've ever seen.

My first experience with short animation was, naturally, old Looney Tunes cartoons played in syndication on morning TV when I was growing up in the '90s. Yet it was through Pixar that I first got the chance to see shorts (either animated or live-action) on a big screen. I still remember the first of Pixar's theatrically attached shorts—Gen's Game, the loopy back-and-forth of an old man ferociously playing himself at chess in a park—better than the feature it accompanied, A Bug's Life. Though I was far, far too young to elucidate how the short's construction hooked me, the way its cuts and "angles" made the old player seem like two distinct people each formulating secret strategies against the other was riotous and thrilling. For the longest time, the lingering, nostalgic giddiness Gen's Game produced made it my favorite of the Pixar shorts.

Until Day & Night. Released 12 years after 1998's Gen's Game, Day & Night was the first Pixar short since that one to be superior to the film it supported. The difference is that the earlier film easily stood out against Pixar's sophomore slump. But Day & Night, that was attached to one of the studio's finest, the unexpectedly poignant, technically superfluous Toy Story 3. At six minutes long, Day & Night proves as much a technical achievement as the feature presentation, and its driving theme as simple and direct yet illuminating and intelligent as the themes of maturation and moving on in Toy Story 3.

True to the time limitations of the form, the short sets itself up quickly. Opening on the usual Pixar 3D animation of an idyllic field, the camera pulls back until it reveals this world as being the tightly contained view of a transparent being existing in 2D space against an infinite black void. Stumbling about in his morning routine, this being happens across someone just like him. Well, almost. Instead of showing an area basked in the morning sun, this other creature offers a window into night. Startled, the two soon engage in a hostile pissing match to demonstrate their superiority, each showing off what goes on at their respective times to impress and cow the other.

The thematic implications are obvious, and only more so as the shortened plot swiftly moves the two from antagonism to mutual admiration and cooperation. Capped off with an old lecture from Wayne Dyer about the importance of embracing the different, Day & Night makes a clear, direct argument for children that warns against xenophobia and just generally hating the unknown. But what makes the film truly masterful is how it's put together. The movement of the two beings in the 2D realm, as well as their moods and expressions, is demonstrated through objects and sounds captured within their portal bodies. For example, when Day wakes up to a rooster crow at the start, thunderclouds communicate the cracking of stiff joints and the sigh of pleasure he emits when he walks into the releasing rush of a waterfall is...well, guess. Even better is the integration of the outer 2D space with the 3D textures within, enhancing the texture of both levels. For a more in-depth account of how this looked in a theater with 3D glasses on, I direct you to Tim Brayton's simply magnificent contemporary review of the short, which he later named the best film of 2010.

Tim's review is so incredible that I'll pretty much stop here, unable to equal his piece, much less add to it. Even his title, "Hegel for Wee Folk," is brilliant, though it also offers perhaps the one area where I can object to him on any grounds. Though the use of 2D and 3D to illustrate the conflict between day and night certainly highlights Hegelian dialectic in several respects, the film's final moments, of the dualities of the two creatures reversing, move beyond Hegel into something more reminiscent of Levinas. When the two stand side by side, the sun setting in one and rising in another (complete with a brief meeting of the two semicircles at the midpoint of both bodies), the self and other invert and become irrelevant, fictitious projections that compel us not into the hatred cautioned against by Dyer but in the fundamental need for empathy as espoused by Levinas. Whether it owes more to Hegel or Levinas, though, Day & Night still broaches at least one of the most challenging philosophers in history, even as it presents a cogent, easily parsed out message for kids. It's one of the best short films I've ever seen.

The Filth and the Fury (Julien Temple, 2000)

The Filth and the Fury opens with an old BBC weather report announcing incoming rain. The metaphor works two-fold, as a literal announcement of the coming storm that is the Sex Pistols, and as a brief look into the starched public face of Britain that is about to have a safety pin shoved through its nose. Indeed, Julien Temple devotes only a few minutes to establishing the adolescences of the Sex Pistols, instead focusing on the social context of the mid-'70s that allowed the band to rise. A few photographs of young Steve Jones and John Lydon are swiftly drowned out by images of trash piling into mountains in the streets during a years-long garbage strike, of punters standing unaffected by a lump of dead rats large enough to be capybaras.

Temple attempts to capture some of the slapdash energy of the band's actual formation, shoved together by impresario Malcolm McLaren and molded into the perfect embodiment of Thatcherian fury and inchoate aggression. Much of the film's first act, in fact, deals with the group's attempt to bash their way into any semblance of musical competence, archival footage and audio of early performances showing off four individuals with no business standing on a stage slowly building a following off their insane look and crazier live act. As the refuse of Britain's youth slowly trickled into whatever shit hole the Pistols played, a movement starts to form, simultaneously proving the shrewdness of McLaren's fashion marketing and turning into something inadvertently genuine.

The fact that the Pistols still enjoy a mythical aura, with numerous repackagings and releases despite the band's two-year, one-LP duration, speaks to the inexplicable charm of the punk rockers. The world's unlikeliest boy band, the Pistols started as guitarist Steve Jones' effort before McLaren stuck his grimy fingers into everything and ginned up notoriety with a parade of staged stunts that revealed the avaricious, capitalistic impulse underneath this supposed movement of musical and sociopolitical revolution even as the kids' vicious tension with McLaren demonstrated the ongoing struggle with that influence, one that proved victorious in the nihilistic dissolution of the group at their moment of glory.

The Pistols stood for a powerful idea, the notion that, truly, anyone could be in a band. Seriously, these people made the Ramones look like Led Zeppelin. They even canned Glen Matlock, the only one among them who had any idea how to play his instrument, to hire Sid Vicious, a kid who only ever used his bass guitar to smash overeager punters who pushed too close to the stage. One look at these guys, and any excuse someone ever cooked up to avoid starting a band evaporated.

Temple has tried to summarize the Pistols on film before, but like the band members themselves, he found himself swayed and misled by McLaren. His 1980 The Great Rock 'N' Roll Swindle is a bizarre mockumentary, started in the aftermath of the group's final concert in January 1978 but before it all truly collapsed. Yet the movie clearly bears McLaren's stamp of approval and manipulative hand, and it's notably today mainly for the brazen, self-serving myths conjured by McLaren. The Filth and the Fury seeks to rectify that shambles of a film by presenting the band's side (including Lydon's and Matlock's, both of whom were omitted from Temple's first go-around with the punks). Curiously, Temple frames their talking heads in shadow, masking their faces as they come clean about their brief time together. They look as if they're in witness protection, hiding from what they wrought.

But if the group won't be on camera now, the film certainly doesn't lack for footage of them back in the day. One of the positive side-effects of McLaren's relentless promotion antics is that nothing the Pistols ever did wasn't captured on tape, so all the legendary, press-baiting disasters—the Screen on the Green, the Queen's Jubilee, their horrifically mis-judged U.S. tour that ended with Rotten's departure after the January show in San Francisco—are not only referenced but shown. Temple's use of contemporary pop culture relics, some of which are a direct response by establishment entertainment to the sudden, feared rise of the band, can be invasive and repetitive, but it's amusing and revealing to see the Pistols slowly incorporated as one of those pop culture elements in a manner that both softens them and only makes them more enduringly snarling and unyielding.

Lydon understands this paradoxical space the band occupies, and he expresses an irritation at the way that the Pistols became iconic in the same dehumanizing, de-individualizing way that all the heroes they sought to tear down had been elevated into some pantheon. Their fashion and sound was instantly co-opted into a uniform sort of anti-conformist conformist expression, disillusioning the band so quickly that three months after releasing their debut, they crumbled at that bitter, defeated gig at Winterland. It was the most punk thing they ever did, cutting McLaren's marionette strings and effectively announcing the end of punk as a means of true expression just as it was becoming the rage. The Pistols helped kickstart punk in the U.K., and Lydon himself would help announce the next stage when he put out his first album with post-punk pioneers Public Image Ltd. by 1978's end. Compared to this flame out, the Ramones' own tenure as the leaders of U.S. punk really did seem like the "century" they brought to a close in 1980.

The Filth and the Fury ends with the same abrupt conclusion of is subject, with only a brief coda spared for Sid Vicious' rapid downfall and his wrenching, pathetic demise a year after the Pistols disbanded. Much as Lydon rages in his silhouette throughout the film against McLaren, his bandmates and the fans who ruined what he wanted to be an individual manifesto, it's Sid's downfall that brings out the most acidic venom in the frontman. Filled with loathing for everyone and himself, Lydon mourns his poor fool of a friend and the greedy forces that destroyed him. It only furthers Sid's image as the emblem of punk, but when Lydon loses his composure talking about him, Vicious turns back into the kid who never made it to 22. Lydon will never truly have his friend back, neither literally nor in the sense that Sid now belongs to the movement that killed him, but for one brief moment, even this burned-out immortal is made just an ordinary human being again. But then, that's what ultimately made him a god in the first place.

Temple attempts to capture some of the slapdash energy of the band's actual formation, shoved together by impresario Malcolm McLaren and molded into the perfect embodiment of Thatcherian fury and inchoate aggression. Much of the film's first act, in fact, deals with the group's attempt to bash their way into any semblance of musical competence, archival footage and audio of early performances showing off four individuals with no business standing on a stage slowly building a following off their insane look and crazier live act. As the refuse of Britain's youth slowly trickled into whatever shit hole the Pistols played, a movement starts to form, simultaneously proving the shrewdness of McLaren's fashion marketing and turning into something inadvertently genuine.

The fact that the Pistols still enjoy a mythical aura, with numerous repackagings and releases despite the band's two-year, one-LP duration, speaks to the inexplicable charm of the punk rockers. The world's unlikeliest boy band, the Pistols started as guitarist Steve Jones' effort before McLaren stuck his grimy fingers into everything and ginned up notoriety with a parade of staged stunts that revealed the avaricious, capitalistic impulse underneath this supposed movement of musical and sociopolitical revolution even as the kids' vicious tension with McLaren demonstrated the ongoing struggle with that influence, one that proved victorious in the nihilistic dissolution of the group at their moment of glory.

The Pistols stood for a powerful idea, the notion that, truly, anyone could be in a band. Seriously, these people made the Ramones look like Led Zeppelin. They even canned Glen Matlock, the only one among them who had any idea how to play his instrument, to hire Sid Vicious, a kid who only ever used his bass guitar to smash overeager punters who pushed too close to the stage. One look at these guys, and any excuse someone ever cooked up to avoid starting a band evaporated.

Temple has tried to summarize the Pistols on film before, but like the band members themselves, he found himself swayed and misled by McLaren. His 1980 The Great Rock 'N' Roll Swindle is a bizarre mockumentary, started in the aftermath of the group's final concert in January 1978 but before it all truly collapsed. Yet the movie clearly bears McLaren's stamp of approval and manipulative hand, and it's notably today mainly for the brazen, self-serving myths conjured by McLaren. The Filth and the Fury seeks to rectify that shambles of a film by presenting the band's side (including Lydon's and Matlock's, both of whom were omitted from Temple's first go-around with the punks). Curiously, Temple frames their talking heads in shadow, masking their faces as they come clean about their brief time together. They look as if they're in witness protection, hiding from what they wrought.

But if the group won't be on camera now, the film certainly doesn't lack for footage of them back in the day. One of the positive side-effects of McLaren's relentless promotion antics is that nothing the Pistols ever did wasn't captured on tape, so all the legendary, press-baiting disasters—the Screen on the Green, the Queen's Jubilee, their horrifically mis-judged U.S. tour that ended with Rotten's departure after the January show in San Francisco—are not only referenced but shown. Temple's use of contemporary pop culture relics, some of which are a direct response by establishment entertainment to the sudden, feared rise of the band, can be invasive and repetitive, but it's amusing and revealing to see the Pistols slowly incorporated as one of those pop culture elements in a manner that both softens them and only makes them more enduringly snarling and unyielding.

Lydon understands this paradoxical space the band occupies, and he expresses an irritation at the way that the Pistols became iconic in the same dehumanizing, de-individualizing way that all the heroes they sought to tear down had been elevated into some pantheon. Their fashion and sound was instantly co-opted into a uniform sort of anti-conformist conformist expression, disillusioning the band so quickly that three months after releasing their debut, they crumbled at that bitter, defeated gig at Winterland. It was the most punk thing they ever did, cutting McLaren's marionette strings and effectively announcing the end of punk as a means of true expression just as it was becoming the rage. The Pistols helped kickstart punk in the U.K., and Lydon himself would help announce the next stage when he put out his first album with post-punk pioneers Public Image Ltd. by 1978's end. Compared to this flame out, the Ramones' own tenure as the leaders of U.S. punk really did seem like the "century" they brought to a close in 1980.

The Filth and the Fury ends with the same abrupt conclusion of is subject, with only a brief coda spared for Sid Vicious' rapid downfall and his wrenching, pathetic demise a year after the Pistols disbanded. Much as Lydon rages in his silhouette throughout the film against McLaren, his bandmates and the fans who ruined what he wanted to be an individual manifesto, it's Sid's downfall that brings out the most acidic venom in the frontman. Filled with loathing for everyone and himself, Lydon mourns his poor fool of a friend and the greedy forces that destroyed him. It only furthers Sid's image as the emblem of punk, but when Lydon loses his composure talking about him, Vicious turns back into the kid who never made it to 22. Lydon will never truly have his friend back, neither literally nor in the sense that Sid now belongs to the movement that killed him, but for one brief moment, even this burned-out immortal is made just an ordinary human being again. But then, that's what ultimately made him a god in the first place.

Sunday, April 22

The Raid: Redemption (Gareth Evans, 2012)

It cannot be denied that the fight choreography in Gareth Evans' The Raid: Redemption ranks among the finest ever put to film. A showcase for the Indonesian martial art of Pencak Silat, The Raid plays a attention-deficit version of Die Hard, replicating that film's sense of economic progression through the floors of an enemy-controlled building but cutting out even the slightest pauses. In theory, it's the perfect film, not wasting any time on plot or even characterization before moving into a police raid on an apartment complex serving as a haven for Jakarta's criminals. The film barely even makes time to establish why an elite squad is about to kick in the doors of this building, and it says even less when they start kicking in heads.

In practice, however, this lack of any establishing narrative swiftly turns The Raid into a tedious exercise, a repetitive display of martial arts prowess that gradually changes from thrilling to dull to, finally, vaguely offensive. Never has the case been more clearly made for the necessity of the storytelling that action fans find a hurdle to surmount before getting to the killing. Late in the film, the crime lord (Ray Sahetapy) at the top of complex immediately throws off the imminent threat of a plot emerging by dismissively saying, "I don't give a shit about 'why' anymore." If he ever did, that puts him one up on Evans.

The first act of The Raid flows without much of a hiccup, the irritating shakycam mildly forgiven by Evans' pacing. The first stage of the titular raid of the building is handled beautifully, with a methodical sweep of the lower floors rolling into a tight montage of the cops silently gagging and cuffing residents. Then it all goes wrong with equal deftness: a child spotting the squad and running into the next room to alert a friend before a bullet strikes him in the neck. Evans almost lets a sense of dread build up, with shots of Tama up in his monitor-filled quarters calmly speaking into the building's PA system and matches of speakers on the floors below booming out his elegant, lightly taunting call to arms. It's such a well-handled moment that the resultant carnage feels something of a letdown of this moody potential.

But damned if the fights aren't amazing. With the moving space generally limited to a narrow corridor or cramped apartment, the choreography manages to find a place for the floods of criminal residents who swarm the small squad who cannot hope for reinforcements. The best fighters, naturally, are the two choreographers, Iko Uwais as the fresh-faced, expectant father Rama and Yayan Ruhian as Tama's brutal henchman Mad Dog, a vicious fighter who purposefully avoids guns so that he might relish a bare-handed kill. Their organization of various sequences, including Rama elegantly dispatching thugs with a tactical knife and Mad Dog taking on a tough sergeant removed from the rest of the team, are initially thrilling. They're so good, in fact, that it would be nice if Evans would let us see any of it. Instead, he erratically cuts around each blow, though his long takes may be even more incoherent, with the camera so roughed up it barely catches anything.

After a time, though, even the fights become so absurd that they lose their splendor. The endless parade of kicks, stabs and gunfire turns what would started out as a brilliantly stripped-down effort into a variant of the Simpsons rake gag with internal bleeding. Indeed, the sequences eventually turn downright comical in their interminable length. Nowhere is this more evident than when Uwais and Ruhian, so excellent in their isolated scenes, come together for a climactic fight that drags on for so long I kept expecting a bikini-clad woman to occasionally walk in front of the camera brandishing a round number on a sign. And though the matching concrete floors and walls facilitate some clever axis inversion on Evans' part as his camera bucks and turns, the drab uniformity of the slum building only makes the parade of martial arts moves more repetitive and droning.

But what truly kept nagging me as the film wore on was the question of why I was supposed to be thrilled by the police stomping out these nondescript people in this building. I wouldn't call it fascistic, per se, certainly not in the way that, say, The Elite Squad is (this is perhaps the one area where the film's lack of story works; if it had even a whisper of one it would likely be in support of this police brutality). There is something, though, unsettling about how gleefully the film moves into a brawl, especially given that the first building resident the audience meets is a decent, meek man just trying to get medicine to his wife. How many others like him are caught in the crossfire of this raid?

The film even makes it clear that the authorities should not even be there, yet it continues to glory in their fight to escape. The last straw, though, is when Evans attempts to toss in some plot twists near the end in a pathetic sop to those growing weary of the senseless fighting. Of course, you can't really have plot twists without a plot to begin with; how can you have any pudding if your don't eat your meat, etc., etc. The Raid is such a hollow exercise, one in which the mastery of its choreography is surrounded by the mediocrity of every other aspect of its design and execution. Lamely propelled by Mike Shinoda's score with all the enthusiasm of someone roped into carting a friend's armoire up a flight of stairs, The Raid embodies the perfunctory, meaningless, hyperviolent slog it charts. Who would think that a film of nothing but action could be so utterly boring?

In practice, however, this lack of any establishing narrative swiftly turns The Raid into a tedious exercise, a repetitive display of martial arts prowess that gradually changes from thrilling to dull to, finally, vaguely offensive. Never has the case been more clearly made for the necessity of the storytelling that action fans find a hurdle to surmount before getting to the killing. Late in the film, the crime lord (Ray Sahetapy) at the top of complex immediately throws off the imminent threat of a plot emerging by dismissively saying, "I don't give a shit about 'why' anymore." If he ever did, that puts him one up on Evans.

The first act of The Raid flows without much of a hiccup, the irritating shakycam mildly forgiven by Evans' pacing. The first stage of the titular raid of the building is handled beautifully, with a methodical sweep of the lower floors rolling into a tight montage of the cops silently gagging and cuffing residents. Then it all goes wrong with equal deftness: a child spotting the squad and running into the next room to alert a friend before a bullet strikes him in the neck. Evans almost lets a sense of dread build up, with shots of Tama up in his monitor-filled quarters calmly speaking into the building's PA system and matches of speakers on the floors below booming out his elegant, lightly taunting call to arms. It's such a well-handled moment that the resultant carnage feels something of a letdown of this moody potential.

But damned if the fights aren't amazing. With the moving space generally limited to a narrow corridor or cramped apartment, the choreography manages to find a place for the floods of criminal residents who swarm the small squad who cannot hope for reinforcements. The best fighters, naturally, are the two choreographers, Iko Uwais as the fresh-faced, expectant father Rama and Yayan Ruhian as Tama's brutal henchman Mad Dog, a vicious fighter who purposefully avoids guns so that he might relish a bare-handed kill. Their organization of various sequences, including Rama elegantly dispatching thugs with a tactical knife and Mad Dog taking on a tough sergeant removed from the rest of the team, are initially thrilling. They're so good, in fact, that it would be nice if Evans would let us see any of it. Instead, he erratically cuts around each blow, though his long takes may be even more incoherent, with the camera so roughed up it barely catches anything.

After a time, though, even the fights become so absurd that they lose their splendor. The endless parade of kicks, stabs and gunfire turns what would started out as a brilliantly stripped-down effort into a variant of the Simpsons rake gag with internal bleeding. Indeed, the sequences eventually turn downright comical in their interminable length. Nowhere is this more evident than when Uwais and Ruhian, so excellent in their isolated scenes, come together for a climactic fight that drags on for so long I kept expecting a bikini-clad woman to occasionally walk in front of the camera brandishing a round number on a sign. And though the matching concrete floors and walls facilitate some clever axis inversion on Evans' part as his camera bucks and turns, the drab uniformity of the slum building only makes the parade of martial arts moves more repetitive and droning.

But what truly kept nagging me as the film wore on was the question of why I was supposed to be thrilled by the police stomping out these nondescript people in this building. I wouldn't call it fascistic, per se, certainly not in the way that, say, The Elite Squad is (this is perhaps the one area where the film's lack of story works; if it had even a whisper of one it would likely be in support of this police brutality). There is something, though, unsettling about how gleefully the film moves into a brawl, especially given that the first building resident the audience meets is a decent, meek man just trying to get medicine to his wife. How many others like him are caught in the crossfire of this raid?

The film even makes it clear that the authorities should not even be there, yet it continues to glory in their fight to escape. The last straw, though, is when Evans attempts to toss in some plot twists near the end in a pathetic sop to those growing weary of the senseless fighting. Of course, you can't really have plot twists without a plot to begin with; how can you have any pudding if your don't eat your meat, etc., etc. The Raid is such a hollow exercise, one in which the mastery of its choreography is surrounded by the mediocrity of every other aspect of its design and execution. Lamely propelled by Mike Shinoda's score with all the enthusiasm of someone roped into carting a friend's armoire up a flight of stairs, The Raid embodies the perfunctory, meaningless, hyperviolent slog it charts. Who would think that a film of nothing but action could be so utterly boring?

Friday, April 20

Puss in Boots: Comparatives & Superlatives

I simply love this movie. One of the best animated films ever. Unforgettable. I used it to practice contrasting comparative and superlative forms

Watch the movie segment and decide which adjectives better apply to Puss in Boots or Kitty Softpaws.

SEXY / FAST / PROVOCATIVE / CHARMING / TALL / CONFIDENT

Write sentences comparing Puss and Kitty, using the adjectives above.

Ex: Kitty (Puss) is sexier than Puss (Kitty).

1 .............................

2.............................

3............................

4............................

5............................

Now decide which adjectives best apply to either Puss in Boots, Kitty Softpaws, Humpty Dumpty or the Golden Goose

Write sentences comparing Puss, Kitty, Humpty Dumpty and Golden Goose.

Ex: Humpty Dumpty is the funniest character.

1.........................................

2........................................

3........................................

4........................................

5........................................

6.......................................

7.......................................

WORKSHEET

MOVIE SEGMENT DOWNLOAD - PUSS IN BOOTS

Watch the movie segment and decide which adjectives better apply to Puss in Boots or Kitty Softpaws.

Puss and Kitty

SEXY / FAST / PROVOCATIVE / CHARMING / TALL / CONFIDENT

Write sentences comparing Puss and Kitty, using the adjectives above.

Ex: Kitty (Puss) is sexier than Puss (Kitty).

1 .............................

2.............................

3............................

4............................

5............................

Now decide which adjectives best apply to either Puss in Boots, Kitty Softpaws, Humpty Dumpty or the Golden Goose

Humpty Dumpty, Kitty and Puss

Golden Goose

FUNNY / STRONG / SHORT / FAMOUS / UGLY / FAT / ELEGANT / TALENTED

Write sentences comparing Puss, Kitty, Humpty Dumpty and Golden Goose.

Ex: Humpty Dumpty is the funniest character.

1.........................................

2........................................

3........................................

4........................................

5........................................

6.......................................

7.......................................

WORKSHEET

MOVIE SEGMENT DOWNLOAD - PUSS IN BOOTS

Random List: 15 More Great Live Albums

I had so much fun writing about some of my favorite live albums the other week that I thought I might share some of my other musical favorites. And since I had so many live albums on the brain and received a number of suggestions for other albums to try, I thought I'd post a few more of my live favorites, as well as some of the new discs I've been trying lately. As with the last post, any recommendations of yours are more than welcome.

Honorable Mention: Deep Purple: Made in Japan

Deep Purple doesn't float my boat the way it used to, but damned if I can't still return to Made in Japan time and again for a rush. It shows off the band's classic lineup (singer Ian Gillan, guitarist Ritchie Blackmore, keyboardist John Lord, bassist Roger Glover, and drummer Ian Paice) at their peak, with Gillan's multi-octave range as thrilling as Blackmore's classical-tinged rock guitar. The two even have a form of duet with an extended "Strange Kind of Woman," with Gillan matching the highest notes Blackmore peels off his fretboard. "Highway Star" and "Lazy" get propulsive renditions, while "Child in Time" has never sounded better, with Blackmore's furious soloing and Gillan's impassioned screams even stronger than on the In Rock version. Yes, you have to suffer through that staple of the bloated '70s live album, the drum solo, but by the time the band reaches its 20-minute freakout take on "Space Truckin', that minor hiccup is more than forgiven. Deep Purple's studio albums got more and more overripe as time went on, but this alternately stretched-but-taut live show hasn't lost an ounce of its raw power.

15. Jeff Buckley, Live at Sin-é

Ed Howard of Only the Cinema mentioned Tim Buckley's live material in the comments for my first post, and that reminded me of his son's pre-Grace recording at a small club in New York. Originally a four-track EP, Live at Sin-é was later expanded into a 2-CD extravaganza that showed off Buckley's astonishing range and vocal power. Though he wasn't as out-there as his dad, Jeff could still draw from a surprising number of influences, and his unbacked, reverb-soaked sets feature covers of artists from Billie Holiday to Edith Piaf to Qawwali icon Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. And the most predictable inspirations, such as Dylan and Van Morrison, are the ones who get the most radical reworking. "The Way That Young Lovers Do," the up-tempo odd-man-out of Astral Weeks, becomes a urgent, scatted, lustful workout that actually makes it sound more like the other songs on Van Morrison's masterpiece than the original version. Likewise, he stretches out Dylan's gorgeous "If You See Her, Say Hello," into a definitive rendition, inserting gulfs of space to better capture the sense of missed chances and wistful regret. The double-CD also offers a glimpse into Buckley pulling his own material together, offering songs like "Grace" and "Mojo Pin" in raw, direct forms that make the beautiful versions eventually released on Buckley's studio album seem overproduced. Every scrap of Buckley's brief career should be treasured, and this hefty set may be the most precious object to come out since his early death.

14. David Bowie, Stage

A toss-up between this and the magnificent concert at the Nassau Coliseum attached to the reissue of his masterpiece, Station to Station. I went with this because of the sheer ballsiness of the track sequencing on the 2005 reissue. Rehabilitated with the reputation fo Low and "Heroes," Stage shows off Bowie's egotistical effrontery, ironically, by highlighting a certain humility in the artist. The first disc faithfully recreates the more Krautrock-ish cuts from Bowie's Berlin albums, which favor the whole band over just Bowie even as they show off his solipsistic turn to pre-New Romantic deadpan pop. And the sequencing of show-stoppers "Warzawa" and "Heroes" as the first two numbers borders on the perverse. Many of these songs privilege the band as much as Bowie himself, though their appearance in a huge rock show at all is an act of hubris. Station to Station marked Bowie's true emergence, finding an emotional immediacy his awkward stabs at R&B utterly lacked, and there's a backwards sort of belated comfort and relaxed tone in Bowie's newfound remove. Stage illustrates this paradox, deliberately alienating the audience with its set order yet bursting with more energy than even the hardest material Bowie made with Mick Ronson.

13. Masada, Live in Sevilla 2000

John Zorn's avant jazz quartet dedicated to creating a new Jewish songbook sports a number of fantastic live albums, but Live in Sevilla strikes the best balance out of all of them. It has the respectful, delicate beauty of the band's 1994 show in Jerusalem, as well as the pummeling, thrashing brute force of the 1999 album cut at Middleheim in Belgium. Joey Baron proves for the umpteenth time that he belongs in the upper echelon of contemporary drummers, while Dave Douglas' trumpet is so dynamic and fluid that it's easy to miss the edge in his playing. Best of all is Zorn, who doesn't seem to play that much anymore (at least on studio compositions). His saxophone playing here shows off the full extent of his playing talent, featuring his wailing squawks in all their screeching hellfire but also the gorgeous quality of his more conventional runs. The two aspects of his sax playing bleed into each other, giving his straight-forward passages grit and his freakouts an appealing sound they do not commonly have. One of the better starting points to get an idea of what the prolific, multifaceted Zorn's all about.

12. Daft Punk, Alive 2007

Sometimes I forget that this is a live album, because it always strikes me more as the ultimate mixtape. Crafted as one giant medley, Alive 2007 flows in and out of the French duo's greatest hits, occasionally colliding tunes so that the looped chorus of "Around the World" barges in on "Television Rules the Nation." Beats transition so fluidly it can be hard to recognize what particular song you are in at any moment. The intricate production quality of the group's studio efforts, and the nature of their music in general, didn't strike me as the sort of thing that would transition to a live setting, yet I've rarely heard an album so thrilling. One of my go-to pump-up discs.

11. J. Geils Band, Blow Your Face Out

I have the same disconnect listening to early J. Geils Band that I do listening to the Faces. I'm so used to American band's subsequent move to pop in the '80s (ditto Rod Stewart's transition to disco and beyond), that to think that both bands used to carry the flag for R&B/ rock revival on their respective sides of the pond. This double-LP should come as a shock to anyone who only knows the J. Geils Band by "Centerfold." The group runs through crunchy, groovy numbers with such tightness that they can effortlessly give the impression of reckless abandon. Powered as much by Magic Dick's harmonica as Peter Wolf's copious frontman talents, the R&B-soaked rock is as pure and exciting as a show gets. In the absence of a proper Faces live album, this is about as good as raunchy, old-school rock in the '70s gets.

10. Iced Earth, Alive in Athens

If I used the term "guilty pleasure," I'd have to employ it for Iced Earth, a band so over-the-top and self-important that they once recorded a 30-minute, multi-part metal recap of the Battle of Gettysburg (and it was AWESOME). Part of me wanted to select Iron Maiden's Live After Death for this list, as it shows off a metal band finding the exact right balance in every respect (cheesy but not too self-parodic, melodic but still hard-edged, composed without being wankish), but Alive in Athens captures that too-much-ness that makes metal so endearingly ridiculous. Recorded in the Florida band's home away from home, the three-CD album runs through the group's greatest hits, a catalog that touches on everything from lost friends to Egyptian mythology and the comic book Spawn. There's also a 16-and-a-half-minute journey through Dante's Inferno, and I am not even kidding. The band seems to just transpose old Steve Harris basslines to guitar, but the energy is non-stop and Matt Barlow's elastic devil-croon and shrieks remain underrated. It's big, goofy fun, and who's not down for that with a live album?

9. Nusrat Fateh Ali Kahn, In Concert in Paris

Jeff Buckley (and Peter Gabriel) introduced me to Nusrat, and I became hooked on his Devotional and Love Songs. I didn't realize, though, that the recordings on those albums were truncated, accessible versions of much longer spirituals. Enter In Concert in Paris, my first exposure to the full extent of Nusrat's power. Leading lengthy chants, Nusrat builds in intensity and passion, reaching for a spiritual plain with his voice that he surely attains. His exuberance is infectious, and anyone, regardless of religious affiliation (or lack thereof) can respond to his boundless energy.

8. Sam Cooke, Live at the Harlem Square Club

I'd been meaning to listen to this for forever, but when Ed mentioned it in his aforementioned comment, I finally got myself a copy, and I instantly fell in love. In the studio, Cooke's singing was ultra-smooth, but live he puts some grit into that gorgeous voice. Cooke's audience control is impeccable; he may not be as explosive as James Brown, but he achieves the same level of crowd ecstasy simply with some banter and his elegantly elongated notes. The backing band goes through the music at mid-tempo, keeping a steady rhythm that never flags but also leaves it to the audience to go crazy. And lose it they do; listen to Cooke's playful build-up of "It's All Right" into "Sentimental Reasons" to hear the shrieks of overload from the ladies in the audience. Interestingly, they don't seem to go wild all at once, instead sounding off in sequence, allowing the listener to aurally chart the way Cooke's effect rippled out, slowly germinating in the head instead of hitting all at once. It may be less outwardly powerful than Live at the Apollo, but in time I think I'll spin this as often as I do Brown's masterpiece.

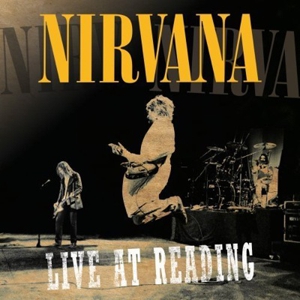

7. Nirvana, Live at Reading

I'm saving Nirvana's Unplugged appearance for a future post about my favorite episodes/performances of that show, but not to be forgotten is their long-bootlegged appearance at the 1992 Reading Festival. It took a long time for me to give Nirvana a chance (judging from my belated enjoyment of Elvis and the Beatles, I just have a thing about initially avoiding sacred cows). But to hear the trio here is to get a sense of the band underneath the ceaseless hype and "voice of a generation" albatross. It's funny, because the gig itself highlights Nirvana's ascendancy; just listen to the massive crowd, who already knows Nevermind by heart, sing along to the instant hits and lose their mind even for the obscurities and covers. There's a perverse failure in this success, with Cobain's tortured punk ethos winning over so many he can no longer be an outsider. That might explain the sardonic energy to the performance, which thrashes harder than Bleach and takes special care to muck up "Smells Like Teen Spirit," which seems like a deliberate act of self-sabotage. But the gift (and, ultimately, the curse) of Cobain's anti-fame rhetoric and behavior was that it only made him more irresistible, and the self-destructive energy he brought to his music and life makes Live at Reading worthy of its legendary status.

6. Johnny Cash, At Folsom Prison

The complete recordings of Cash's day at Folsom undo its mythos somewhat, revealing that the roar that greets Cash's laconic, self-deprecating introduction ("Hello, I'm Johnny Cash") was coached. But the music never fails to satisfy. The second Cash rolls into "Folsom Prison Blues," it's obvious he has his crowd hooked. Cash's outlaw image is somewhat overinflated, but to hear him here, no one could mistake the effortlessness with which he connects with these convicts. The songs range from the vicious (a rip-snorting version of "Cocaine Blues") to the mournful ("I'm Here to Get My Baby Out of Jail") to the mordantly funny ("25 Minutes to Go"), and the inmates' approval is shouted throughout. The original album still more than suffices — it quickly becomes evident why the second show unearthed by the complete box was left out; it's nearly the same setlist but lacks the energy and spontaneity of the first set). The Rolling Stones spent more than a decade trying to seem as hard as Cash casually does in an hour.

5. Led Zeppelin, How the West Was Won

I slipped out of my Led Zeppelin fandom for a few years, exhausted from overplay. But the same album that brought me back was the one that helped to push me away. With its frankly ridiculous jam lengths, How the West Was Won is as much belated but definitive proof of the service punk rock did us all by shoving this sort of thing out of fashion as it is a thunderous snapshot of the world's greatest band at its peak and a nostalgic reminder of some of the magic that was lost when they and their style became unfashionable. Recorded over two nights in California in 1972, How the West Was Won captures Zep at the pinnacle of their ability and energy. Plant hadn't yet ravaged his larynx, and the jams, though free of any grounding element, still have a curiosity to them that makes their meandering drifts more fascinating and suspenseful than tedious. Yeah, Bonham's drum solo is still a chore, but there's a kind of joy to be had even then in witnessing a band with such a hold on the world that they could do anything they wanted.

4. The Rolling Stones: Brussels Affair

I had no idea this had been officially released. It was going to be one of the top picks for a favorite bootlegs post I was mulling over. I'm overwhelmed with joy knowing that one of the best rock shows ever is now legitimately available. I love the Stones but always felt they tried a bit too hard to seem tough and casually cool, but this set brings down the house so effortlessly that suddenly I wonder if they weren't really badasses all along. The Stones are just on fire here, running through "Rip This Joint" at even faster speed than the belligerent studio version on Exile on Main St., while "Midnight Rambler" gets its requisite live workout. The real star here may be Mick Taylor, who would be gone from the band in a year's time over disputes and what seems like professional jealousy on Richards' part. That's only my conjecture, mind, and to listen to the pair of guitarists here, the only reasonable conclusion that can be reached is that if these two hated each other, at least they pushed each other to better and better playing out of spite. Their interplay on songs like "All Down the Line" and "Jumpin' Jack Flash" are definitive versions. The Stones have been coasting for 30 years now, but to hear them here, at the height of their fame, you can still catch a band hungry to please a crowd.

3. Talking Heads: The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads

Capturing the band at two critical points, its 1977 New Wave ascendancy and its '80s Eno-fication, The Name of This Band is Talking Heads two halves sound like the work of two distinct groups even as they simply must have been recorded by the same group. The first disc shows off the early Heads at their jittery best, with David Byrne laconically introducing songs ("The name of this song is called 'New Feeling,' and that's what it's about") and leading the original quartet through knotty angular rhythms. The post-Remain in Light disc rolls out the expanded lineup, building on the band's original focus on complex, precise patterns with African polyrhythms inspired by Fela Kuti. But if the percussion got more complicated, it also got more groovy, giving a strangely inviting, exuberant taste to the esoterica of Byrne's lyrics and style. Faster and more rubbery than their studio counterparts, the renditions turn even the most mathematical tune into something danceable. The album's title reminds you not to preface the band's name with "The." The music within will make you care enough to follow the instruction.

2. Kraftwerk, Minimum-Maximum

Listening to Kraftwerk now is like watching 2001: A Space Odyssey. On the one hand, it's obviously dated, carving out a vision of the future that did not come to pass, but on the other it is still fresh and provoking in a way that marks it as eternally ahead-of-its-time. And with Minimum-Maximum, one can see that Kraftwerk, despite continuing to work with a classic electronic sound, does not merely replicate its old albums. If the band is all about a processed, perfect sound, they recognize that goal as one of constant evolution: check out the reworked and remixed songs here, most notably a shortened version of "Autobahn" that shows off the technical innovation of the number while twisting it more openly into pop than the side-length freeway soundtrack of the studio version. Kraftwerk, despite some equipment tweaks, might be using now-outdated technology, but the rest of the world finally caught up to their work, which sounds poppier in the context of a live performance than it does on their vacuum-sealed LPs. Before hearing this, my consideration of Kraftwerk only extended as far as respectful admiration for their deadpan machinations. Then I heard a band who, though slower and statelier, were no less exhilarating than Daft Punk.

1. The Stooges, Metallic K.O.

I have a fascination with performances that invite audience hostility. One of my favorite comedy albums is Neil Hamburger's Hot February Night, not for the anti-humor (even taking into account the deliberately shocking/alienating rape and misogyny humor, it's a bit too much to bear) but for the fearlessness with which Gregg Turkington's alter ego withstands the fury of a crowd. Metallic K.O. is the Hot February Night of music, the sound of a band and crowd locked into a hate-fuck that brings out the best/worst in both. The Stooges' studio albums sounded sloppy and abrasive, but nothing compares to these ramshackle performances captured in 1973 and the band's last gig in February 1974. Recorded by a fan and sent to James Williamson, even the sound of this glorified bootleg is disastrous, but that only adds to the effect. As the band lumbers through its inchoate, piercing howls of young angst and rage, the audience gently moves from indifference to open hatred, and Iggy eggs them on. And damned if Lester Bangs wasn't right: after Iggy concludes the sneering "Cock in My Pocket" by roundly inviting the crowd to throw things and introducing the band members to a chorus of boos, you really can hear a beer bottle shatter near a mic and some equipment momentarily fry. The crap audio fidelity does the music justice, and if you ever want to hear the id of rock 'n' roll fully unleashed, look no further.

Honorable Mention: Deep Purple: Made in Japan

Deep Purple doesn't float my boat the way it used to, but damned if I can't still return to Made in Japan time and again for a rush. It shows off the band's classic lineup (singer Ian Gillan, guitarist Ritchie Blackmore, keyboardist John Lord, bassist Roger Glover, and drummer Ian Paice) at their peak, with Gillan's multi-octave range as thrilling as Blackmore's classical-tinged rock guitar. The two even have a form of duet with an extended "Strange Kind of Woman," with Gillan matching the highest notes Blackmore peels off his fretboard. "Highway Star" and "Lazy" get propulsive renditions, while "Child in Time" has never sounded better, with Blackmore's furious soloing and Gillan's impassioned screams even stronger than on the In Rock version. Yes, you have to suffer through that staple of the bloated '70s live album, the drum solo, but by the time the band reaches its 20-minute freakout take on "Space Truckin', that minor hiccup is more than forgiven. Deep Purple's studio albums got more and more overripe as time went on, but this alternately stretched-but-taut live show hasn't lost an ounce of its raw power.

15. Jeff Buckley, Live at Sin-é

Ed Howard of Only the Cinema mentioned Tim Buckley's live material in the comments for my first post, and that reminded me of his son's pre-Grace recording at a small club in New York. Originally a four-track EP, Live at Sin-é was later expanded into a 2-CD extravaganza that showed off Buckley's astonishing range and vocal power. Though he wasn't as out-there as his dad, Jeff could still draw from a surprising number of influences, and his unbacked, reverb-soaked sets feature covers of artists from Billie Holiday to Edith Piaf to Qawwali icon Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan. And the most predictable inspirations, such as Dylan and Van Morrison, are the ones who get the most radical reworking. "The Way That Young Lovers Do," the up-tempo odd-man-out of Astral Weeks, becomes a urgent, scatted, lustful workout that actually makes it sound more like the other songs on Van Morrison's masterpiece than the original version. Likewise, he stretches out Dylan's gorgeous "If You See Her, Say Hello," into a definitive rendition, inserting gulfs of space to better capture the sense of missed chances and wistful regret. The double-CD also offers a glimpse into Buckley pulling his own material together, offering songs like "Grace" and "Mojo Pin" in raw, direct forms that make the beautiful versions eventually released on Buckley's studio album seem overproduced. Every scrap of Buckley's brief career should be treasured, and this hefty set may be the most precious object to come out since his early death.

14. David Bowie, Stage

A toss-up between this and the magnificent concert at the Nassau Coliseum attached to the reissue of his masterpiece, Station to Station. I went with this because of the sheer ballsiness of the track sequencing on the 2005 reissue. Rehabilitated with the reputation fo Low and "Heroes," Stage shows off Bowie's egotistical effrontery, ironically, by highlighting a certain humility in the artist. The first disc faithfully recreates the more Krautrock-ish cuts from Bowie's Berlin albums, which favor the whole band over just Bowie even as they show off his solipsistic turn to pre-New Romantic deadpan pop. And the sequencing of show-stoppers "Warzawa" and "Heroes" as the first two numbers borders on the perverse. Many of these songs privilege the band as much as Bowie himself, though their appearance in a huge rock show at all is an act of hubris. Station to Station marked Bowie's true emergence, finding an emotional immediacy his awkward stabs at R&B utterly lacked, and there's a backwards sort of belated comfort and relaxed tone in Bowie's newfound remove. Stage illustrates this paradox, deliberately alienating the audience with its set order yet bursting with more energy than even the hardest material Bowie made with Mick Ronson.

13. Masada, Live in Sevilla 2000

John Zorn's avant jazz quartet dedicated to creating a new Jewish songbook sports a number of fantastic live albums, but Live in Sevilla strikes the best balance out of all of them. It has the respectful, delicate beauty of the band's 1994 show in Jerusalem, as well as the pummeling, thrashing brute force of the 1999 album cut at Middleheim in Belgium. Joey Baron proves for the umpteenth time that he belongs in the upper echelon of contemporary drummers, while Dave Douglas' trumpet is so dynamic and fluid that it's easy to miss the edge in his playing. Best of all is Zorn, who doesn't seem to play that much anymore (at least on studio compositions). His saxophone playing here shows off the full extent of his playing talent, featuring his wailing squawks in all their screeching hellfire but also the gorgeous quality of his more conventional runs. The two aspects of his sax playing bleed into each other, giving his straight-forward passages grit and his freakouts an appealing sound they do not commonly have. One of the better starting points to get an idea of what the prolific, multifaceted Zorn's all about.

12. Daft Punk, Alive 2007

Sometimes I forget that this is a live album, because it always strikes me more as the ultimate mixtape. Crafted as one giant medley, Alive 2007 flows in and out of the French duo's greatest hits, occasionally colliding tunes so that the looped chorus of "Around the World" barges in on "Television Rules the Nation." Beats transition so fluidly it can be hard to recognize what particular song you are in at any moment. The intricate production quality of the group's studio efforts, and the nature of their music in general, didn't strike me as the sort of thing that would transition to a live setting, yet I've rarely heard an album so thrilling. One of my go-to pump-up discs.

11. J. Geils Band, Blow Your Face Out

I have the same disconnect listening to early J. Geils Band that I do listening to the Faces. I'm so used to American band's subsequent move to pop in the '80s (ditto Rod Stewart's transition to disco and beyond), that to think that both bands used to carry the flag for R&B/ rock revival on their respective sides of the pond. This double-LP should come as a shock to anyone who only knows the J. Geils Band by "Centerfold." The group runs through crunchy, groovy numbers with such tightness that they can effortlessly give the impression of reckless abandon. Powered as much by Magic Dick's harmonica as Peter Wolf's copious frontman talents, the R&B-soaked rock is as pure and exciting as a show gets. In the absence of a proper Faces live album, this is about as good as raunchy, old-school rock in the '70s gets.

10. Iced Earth, Alive in Athens

If I used the term "guilty pleasure," I'd have to employ it for Iced Earth, a band so over-the-top and self-important that they once recorded a 30-minute, multi-part metal recap of the Battle of Gettysburg (and it was AWESOME). Part of me wanted to select Iron Maiden's Live After Death for this list, as it shows off a metal band finding the exact right balance in every respect (cheesy but not too self-parodic, melodic but still hard-edged, composed without being wankish), but Alive in Athens captures that too-much-ness that makes metal so endearingly ridiculous. Recorded in the Florida band's home away from home, the three-CD album runs through the group's greatest hits, a catalog that touches on everything from lost friends to Egyptian mythology and the comic book Spawn. There's also a 16-and-a-half-minute journey through Dante's Inferno, and I am not even kidding. The band seems to just transpose old Steve Harris basslines to guitar, but the energy is non-stop and Matt Barlow's elastic devil-croon and shrieks remain underrated. It's big, goofy fun, and who's not down for that with a live album?

9. Nusrat Fateh Ali Kahn, In Concert in Paris

Jeff Buckley (and Peter Gabriel) introduced me to Nusrat, and I became hooked on his Devotional and Love Songs. I didn't realize, though, that the recordings on those albums were truncated, accessible versions of much longer spirituals. Enter In Concert in Paris, my first exposure to the full extent of Nusrat's power. Leading lengthy chants, Nusrat builds in intensity and passion, reaching for a spiritual plain with his voice that he surely attains. His exuberance is infectious, and anyone, regardless of religious affiliation (or lack thereof) can respond to his boundless energy.

8. Sam Cooke, Live at the Harlem Square Club

I'd been meaning to listen to this for forever, but when Ed mentioned it in his aforementioned comment, I finally got myself a copy, and I instantly fell in love. In the studio, Cooke's singing was ultra-smooth, but live he puts some grit into that gorgeous voice. Cooke's audience control is impeccable; he may not be as explosive as James Brown, but he achieves the same level of crowd ecstasy simply with some banter and his elegantly elongated notes. The backing band goes through the music at mid-tempo, keeping a steady rhythm that never flags but also leaves it to the audience to go crazy. And lose it they do; listen to Cooke's playful build-up of "It's All Right" into "Sentimental Reasons" to hear the shrieks of overload from the ladies in the audience. Interestingly, they don't seem to go wild all at once, instead sounding off in sequence, allowing the listener to aurally chart the way Cooke's effect rippled out, slowly germinating in the head instead of hitting all at once. It may be less outwardly powerful than Live at the Apollo, but in time I think I'll spin this as often as I do Brown's masterpiece.

7. Nirvana, Live at Reading

I'm saving Nirvana's Unplugged appearance for a future post about my favorite episodes/performances of that show, but not to be forgotten is their long-bootlegged appearance at the 1992 Reading Festival. It took a long time for me to give Nirvana a chance (judging from my belated enjoyment of Elvis and the Beatles, I just have a thing about initially avoiding sacred cows). But to hear the trio here is to get a sense of the band underneath the ceaseless hype and "voice of a generation" albatross. It's funny, because the gig itself highlights Nirvana's ascendancy; just listen to the massive crowd, who already knows Nevermind by heart, sing along to the instant hits and lose their mind even for the obscurities and covers. There's a perverse failure in this success, with Cobain's tortured punk ethos winning over so many he can no longer be an outsider. That might explain the sardonic energy to the performance, which thrashes harder than Bleach and takes special care to muck up "Smells Like Teen Spirit," which seems like a deliberate act of self-sabotage. But the gift (and, ultimately, the curse) of Cobain's anti-fame rhetoric and behavior was that it only made him more irresistible, and the self-destructive energy he brought to his music and life makes Live at Reading worthy of its legendary status.

6. Johnny Cash, At Folsom Prison

The complete recordings of Cash's day at Folsom undo its mythos somewhat, revealing that the roar that greets Cash's laconic, self-deprecating introduction ("Hello, I'm Johnny Cash") was coached. But the music never fails to satisfy. The second Cash rolls into "Folsom Prison Blues," it's obvious he has his crowd hooked. Cash's outlaw image is somewhat overinflated, but to hear him here, no one could mistake the effortlessness with which he connects with these convicts. The songs range from the vicious (a rip-snorting version of "Cocaine Blues") to the mournful ("I'm Here to Get My Baby Out of Jail") to the mordantly funny ("25 Minutes to Go"), and the inmates' approval is shouted throughout. The original album still more than suffices — it quickly becomes evident why the second show unearthed by the complete box was left out; it's nearly the same setlist but lacks the energy and spontaneity of the first set). The Rolling Stones spent more than a decade trying to seem as hard as Cash casually does in an hour.

5. Led Zeppelin, How the West Was Won

I slipped out of my Led Zeppelin fandom for a few years, exhausted from overplay. But the same album that brought me back was the one that helped to push me away. With its frankly ridiculous jam lengths, How the West Was Won is as much belated but definitive proof of the service punk rock did us all by shoving this sort of thing out of fashion as it is a thunderous snapshot of the world's greatest band at its peak and a nostalgic reminder of some of the magic that was lost when they and their style became unfashionable. Recorded over two nights in California in 1972, How the West Was Won captures Zep at the pinnacle of their ability and energy. Plant hadn't yet ravaged his larynx, and the jams, though free of any grounding element, still have a curiosity to them that makes their meandering drifts more fascinating and suspenseful than tedious. Yeah, Bonham's drum solo is still a chore, but there's a kind of joy to be had even then in witnessing a band with such a hold on the world that they could do anything they wanted.

4. The Rolling Stones: Brussels Affair

I had no idea this had been officially released. It was going to be one of the top picks for a favorite bootlegs post I was mulling over. I'm overwhelmed with joy knowing that one of the best rock shows ever is now legitimately available. I love the Stones but always felt they tried a bit too hard to seem tough and casually cool, but this set brings down the house so effortlessly that suddenly I wonder if they weren't really badasses all along. The Stones are just on fire here, running through "Rip This Joint" at even faster speed than the belligerent studio version on Exile on Main St., while "Midnight Rambler" gets its requisite live workout. The real star here may be Mick Taylor, who would be gone from the band in a year's time over disputes and what seems like professional jealousy on Richards' part. That's only my conjecture, mind, and to listen to the pair of guitarists here, the only reasonable conclusion that can be reached is that if these two hated each other, at least they pushed each other to better and better playing out of spite. Their interplay on songs like "All Down the Line" and "Jumpin' Jack Flash" are definitive versions. The Stones have been coasting for 30 years now, but to hear them here, at the height of their fame, you can still catch a band hungry to please a crowd.

3. Talking Heads: The Name of This Band Is Talking Heads

Capturing the band at two critical points, its 1977 New Wave ascendancy and its '80s Eno-fication, The Name of This Band is Talking Heads two halves sound like the work of two distinct groups even as they simply must have been recorded by the same group. The first disc shows off the early Heads at their jittery best, with David Byrne laconically introducing songs ("The name of this song is called 'New Feeling,' and that's what it's about") and leading the original quartet through knotty angular rhythms. The post-Remain in Light disc rolls out the expanded lineup, building on the band's original focus on complex, precise patterns with African polyrhythms inspired by Fela Kuti. But if the percussion got more complicated, it also got more groovy, giving a strangely inviting, exuberant taste to the esoterica of Byrne's lyrics and style. Faster and more rubbery than their studio counterparts, the renditions turn even the most mathematical tune into something danceable. The album's title reminds you not to preface the band's name with "The." The music within will make you care enough to follow the instruction.

2. Kraftwerk, Minimum-Maximum

Listening to Kraftwerk now is like watching 2001: A Space Odyssey. On the one hand, it's obviously dated, carving out a vision of the future that did not come to pass, but on the other it is still fresh and provoking in a way that marks it as eternally ahead-of-its-time. And with Minimum-Maximum, one can see that Kraftwerk, despite continuing to work with a classic electronic sound, does not merely replicate its old albums. If the band is all about a processed, perfect sound, they recognize that goal as one of constant evolution: check out the reworked and remixed songs here, most notably a shortened version of "Autobahn" that shows off the technical innovation of the number while twisting it more openly into pop than the side-length freeway soundtrack of the studio version. Kraftwerk, despite some equipment tweaks, might be using now-outdated technology, but the rest of the world finally caught up to their work, which sounds poppier in the context of a live performance than it does on their vacuum-sealed LPs. Before hearing this, my consideration of Kraftwerk only extended as far as respectful admiration for their deadpan machinations. Then I heard a band who, though slower and statelier, were no less exhilarating than Daft Punk.

1. The Stooges, Metallic K.O.

I have a fascination with performances that invite audience hostility. One of my favorite comedy albums is Neil Hamburger's Hot February Night, not for the anti-humor (even taking into account the deliberately shocking/alienating rape and misogyny humor, it's a bit too much to bear) but for the fearlessness with which Gregg Turkington's alter ego withstands the fury of a crowd. Metallic K.O. is the Hot February Night of music, the sound of a band and crowd locked into a hate-fuck that brings out the best/worst in both. The Stooges' studio albums sounded sloppy and abrasive, but nothing compares to these ramshackle performances captured in 1973 and the band's last gig in February 1974. Recorded by a fan and sent to James Williamson, even the sound of this glorified bootleg is disastrous, but that only adds to the effect. As the band lumbers through its inchoate, piercing howls of young angst and rage, the audience gently moves from indifference to open hatred, and Iggy eggs them on. And damned if Lester Bangs wasn't right: after Iggy concludes the sneering "Cock in My Pocket" by roundly inviting the crowd to throw things and introducing the band members to a chorus of boos, you really can hear a beer bottle shatter near a mic and some equipment momentarily fry. The crap audio fidelity does the music justice, and if you ever want to hear the id of rock 'n' roll fully unleashed, look no further.

Tuesday, April 17

Monsieur Lazhar (Philippe Falardeau, 2012)

I'm afraid I didn't particularly take to Monsieur Lazhar, the classroom drama that received an Academy Award nomination for best foreign-language film at this year's Oscars. Trying desperately to avoid the usual pitfalls of moralizing, treacly schoolyard films, Lazhar ultimately loses the thread of its subtle expression and simply treads water. It also makes obvious what had earlier been broached with such elegant subtlety that I couldn't help but feel let down by its lack of faith in the audience. Its resolution is easily uneasy, downbeat in that facile manner that strives for ambiguity but effectively seals off the narrative. There are some fine performances, but the whole failed to stay with me.

My full review is up now at Spectrum Culture.

My full review is up now at Spectrum Culture.

Sunday, April 15

The Cabin in the Woods (Drew Goddard, 2012)

[Warning: Contains mild first-act spoilers after the jump]

Drew Goddard made his feature debut with 2008's Cloverfield, penning the film's ambitious but misguided script that sought to comment on modern mindsets regarding the documentation of our lives via the kaiju film genre. His idea, clever on paper, was that a group of privileged New York yuppies contending with 9/11-esque frenzy would nevertheless ensure that their bewilderment and horror was caught on video for posterity, or at least for YouTube hits. Unfortunately for Goddard, director Matt Reeves' muddled direction and some dire acting performances sapped whatever potential the script contained, resulting in a lifeless film that only occasionally hinted at just how far it wanted to go with its metaphor.

By teaming up with his old Buffy and Angel boss Joss Whedon, however, Goddard got a second chance to say something with horror, and The Cabin in the Woods truly delivers on his promise. At times recalling Sam Raimi's 2009 return-to-form Drag Me to Hell, The Cabin in the Woods differs from that film, and other self-aware horror movies, by not merely calling attention to horror tropes but breaking them down, working out how they apply to the genre, as well as how filmmakers (and participatory audiences) apply them to it. To oversimplify it into a pitch, where movies such as Drag Me to Hell or the Scream series are about horror films, The Cabin in the Woods is about horror itself.

Unlike the first-person perspective satire of Cloverfield, Cabin in the Woods pulls back to get a fuller picture of its subject. The two do, however, share an inversion of expectations in their narrative focus. Cloverfield's overwhelmed shaky-cam cared less for the monster than the characters. Awful, wafer-thin characters, sure, but there was something radical about this shift in attention. Likewise, The Cabin in the Woods, named after a subgenre in which young people find themselves trapped in the middle of nowhere as monsters thin their ranks, does not even open with the group of undergrads traveling to the titular, doomed getaway. Instead, it begins with two middle-aged officials (Richard Jenkins and Bradley Whitford) in some mysterious, vast compound. It's a bewildering start, but one that instantly lets the audience know that something is up, which is confirmed when the film then moves to its quintet of young people prepping for their weekend trip and the camera quickly pulls back to reveal that the kids are being closely monitored. With Cloverfield, Goddard made an epic subgenre intimate; with this, he makes a visceral subgenre analytical and observant.

The omniscient third-person suits him. Goddard and Whedon waste no time poking fun at conventions, presenting the thick-headed jock (Thor himself, Chris Hemsworth) as a kind, intelligent person and gradually suggesting the the tag-along stoner (Fran Kanz, more at home here than as a similarly snide character on Dollhouse) is more aware of the situation than his sober pals. The events that happen to these people at the cabin are also handled humorously, using both subtle visualization and open reference to call out some of the sillier aspects of this kind of movie. Had the film remained on this level, its cheek would have been funny, but hardly revelatory. By taking in a larger picture, Goddard can move beyond lazy reflexive humor into true metatextual insight.