A moment near the beginning of Olivier Assayas' 5-1/2 hour epic

Carlos recalled the opening shot of another 2010 masterpiece:

The Social Network. Both films place the protagonist at a table with his lover. Carlos the Jackal, like Mark Zuckerberg, is unformed here, all ambition but no substance. And like Erica Albright, Carlos' female companion sees right through his bullshit: where Zuckerberg's girlfriend pegs him an "asshole," Carlos' woman recognizes the "bourgeois arrogance" behind his revolutionary zeal. Like Zuckerberg, Carlos would gain notoriety for linking people across the world. Only where the Harvard freshman gave collegiate youth a forum to broadcast drunken musings on the web, Ilich Ramírez Sánchez represented the dawn of the modern terrorist, capable of slipping in and out of cells anywhere on Earth.

Carlos the Jackal, like Zuckerberg, would become a defining icon of his generation even as both remained relative unknowns to those who vilified (and worshiped) them.

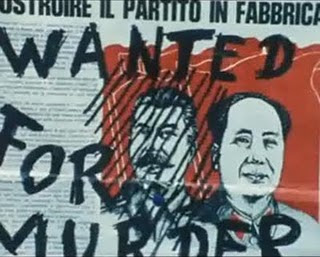

Carlos, Assayas' finest film since...his last one, uses its excessive length to tear down the mythos surrounding the Jackal, the man who popularized, possibly even invented, the notion of airplane hijacking by terrorists. For years, a single photograph of Carlos, showing a pudgy, smirking man, became the symbol of terrorism, a vision of arrogant cool that today looks absurd. Just as Steven Soderbergh attempted to undermine the iconic photograph of Che Guevara, so too does Assayas dig into his own subject's portrait to demystify the Jackal.

His early actions portray an idealist whose incompetence overshadows his zeal. His first assignment for the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, to execute a Zionist businessman, ends in failure when his gun jams. Later, he and another take a missile launcher to an airstrip, only to to twice miss the plane they are aiming at on the tarmac. Eventually, he starts to work with the Japanese Red Army on some raids in The Hague and Paris, always staying a safe distance away from any action. Even his first significant success, killing French police who track him down via an informant, comes only because he stops paying attention and practically invites the detectives over. But a paper prints the headline "Carlos: 3-0" afterward, assuring the terrorist of his victory. Yet onward he moves, and Assayas communicates Sánchez's restlessness with a graceful but frenetic camera, not resorting to shakycam but never pausing. Assayas uses this direction to quickly paint a portrait of a man able to outpace his own failure, somehow taking every minor thing he does right along with him and leaving the detritus behind.

Carlos himself detests immobility. He views terrorism through the same romantic lens that so many view freedom fighters, and uses the image of a dangerous man to fashion himself into something of a rock star. The locations of the film change seemingly with every cut of the camera, globetrotting on fast-forward to show Carlos and co. stirring up trouble wherever they can. As if watching a James Bond movie, we see a parade of women undressing for Sánchez as his clothes become increasingly fashionable. In one memorable scene, he seduces a woman by rubbing a live grenade over her body, demonstrating in a flash his entire perception of his actions. When he must lie low, sent to the Middle Eastern desert to train a PFLP camp, the sudden decrease in movement affects Carlos so much that even his body suddenly looks amorphous and without structure. By the end of the first part, I wondered if Sánchez agreed to train as a "proper" terrorist only so he could feel justified wearing the beret he adds to his wardrobe.

Seeking to prove his credentials, Carlos will do anything he is asked, and the PFLP humorously seems to care more about the moderates within their own cause than the imperial powers they believe keep them down. Even Yasser Arafat is mocked and denounced for daring to even meet with Israeli representatives. Carlos and the other soldiers are convinced that they must purify their own side to better attack the enemy with a unified front, but we can read between the lines and guess that the ones actually in charge of the terrorist organizations realize that an attack on one of those imperialist powers will bring the military might of those nations to bear on nations utterly ill-equipped to handle a squadron of bombers suddenly entering Syrian or Libyan airspace. The cleansing of their own house allows them to look busy and fearsome while not getting much of substance done.

Assayas makes that underlying motivation clear by shooting Carlos' defining moment, the raid and subsequent hostage-taking at the headquarters of OPEC in Vienna on December 21, 1975, from a perspective that destroys any notion that the defining moment in Carlos' life was anything but an absurd waste. Sent to kill the representatives for Iran and Saudi Arabia for breaking the OPEC embargo, Carlos and his team successfully break into the building, quell resistance and separate the representatives by how friendly they are to "the cause." For all of Ronald Reagan's mistakes and all the things about his administration I find at best neglectful and at worst abhorrent, he was absolutely correct to lay down the "we don't negotiate with terrorists" policy, and, indeed, the Swiss authorities look like clowns as they acquiesce to every demand made by Carlos. Swiss TV stations play a prepared, pro-Palestinian statement every two hours, Sánchez's demanded DC-9 plane is obtained and Swiss authorities even take one of the terrorists in their custody, a wounded German named Hans‑Joachim Klein, and release him in his hospital bed to board the plane.

Of course, not everything goes according to plan. During the raid, Carlos locks one man in his office and leaves, failing to consider that a working telephone is also in that office. Nada, a ferocious vision of mid-'70s punk incarnate, kills a cop, then sends his body down in an elevator to alert those on other floors of what's going on. And when they reach the airport, Carlos is stymied to learn that, while he got the DC-9 he requested, he did not check the aircraft's range, learning from the assigned pilot that it cannot reach Baghdad and must go to Algiers. As with everything that came before, Carlos manages to succeed only through luck and the shared incompetence of others.

The raid and escape sequence, dominating the entire first half of the second part, delineates Carlos from his hero, Che. Assayas, who, on the basis of this

fantastic interview with Glenn Kenny, saw and understood what Soderbergh was trying to do with his own epic -- to bypass biography to focus on strategy, separates Che's ability to rigorously plan and execute a revolution according to plan from the Jackal's more impulsive behavior. Before he kills the Saudi Arabian oil minister, he has a heart-to-heart with the man about his reluctance to assassinate the representative of a nation whom he usually considers an ally. The minister is so confused by this chat that he pushes his luck by asking why the terrorist is even speaking to him. Later, Carlos decides to trade both the Saudi minister and the Iranian finance minister with the rest of the hostages for a massive sum of money (which he claims for the cause, of course). We also get to see the brash, naïve views of his team. As Carlos takes a step toward more political thinking, or at least self-serving greed, his comrades rage at the idea of failing their prime objective for cash. Amusingly, their fiery rants make Carlos' plan sound mature. After watching Red Army members shoot at a portrait of former French president Georges Pompidou at the French embassy in The Hague (despite Pompidou having already died in '74) and the actions of people like Nada in the OPEC scenario, we almost sympathize with Carlos, until we realize he has become the moderate he hates, regardless of how much he continues to speak against moderation over the resulting decades.

From the second half of the middle part through the end,

Carlos moves to detail the banality of the Jackal's life of crime, which seems more mercenary than extremist. He continues to do the bidding of others, others who are becomingly increasingly weary of Carlos' fame and his love of it. The PFLP throws him out for failing to kill the two intended targets of the OPEC raid, and the East German Stasi is too preoccupied with its inner turmoil over potential antisemitism vs. anti-Zionism to offer much to Carlos when he relocates to East Berlin. The split between hating Israel and hating Jews comes to a head with the 1976 hijacking of the Air France flight to Entebbe, foiled by IDF agents. Klein, the terrorist wounded in the OPEC raid, notes with horror that before the Israelis stopped the hijacking, the PFLP members involved separated the Jews on-board from the rest of the passengers, preparing them for the kill. By 1977, Klein has left Carlos' independent terrorist cell and confessed his crimes to the German paper Der Spiegel, placing the other terrorists in jeopardy.

Ergo, the final part in the three-episode miniseries depicts Carlos as a man slowly, quietly coming undone from paranoia and the mounting realization that he's a has-been. As a journalist seeking an interview rightly notes, without the papers, there would be no Carlos. Thus, when his activity begins to slow in the '80s, he's left to continue evading capture, no longer acting on the offense but the defense. We are treated to mad sights like Carlos and his German comrade, Johannes Weinrich, hiding guns in the mansion Carlos buys as a "home base" (which sounds by this point to be the hip, geopolitical update to calling a man's house his "castle") before taking Carlos' wife to the hospital to give birth. We watch many of Sánchez's late dealings with terrorist-friendly governments on surveillance video, seeing beyond the discussions to note that even those ostensibly sympathetic to Carlos' convictions had begun recording him in case they needed to burn the man. Finally, Carlos, fat, tired and dealing with testicular pain, is betrayed by his own comrades who view him as nothing more than a liability and a waste of resources. When he's captured, he regrets that he won't be able to get that liposuction he was planning. A fine end for a committed Marxist.

The chief complaint I've heard registered against the film is that this last third is too slow, too concerned with staking out the banality of Carlos' life when that had already been made clear. But I found the final part the most revealing, especially because Édgar Ramírez's performance reaches its peak at the end. I've not yet commented on what is easily the finest acting work of the year, reluctant to approach the subject too soon for fear of never getting back on track with the rest of the film's greatness. Resembling a Hispanic Mark Ruffalo, Ramírez exudes animal magnetism: you have to keep reminding yourself that Carlos is, ultimately, just a foot soldier doing the work of superiors because he has a way of convincing all those around him he's a leader. He even seduces his second wife, the German revolutionary Magdalena Kopp, from being a radical feminist to a classical housewife -- in one of the film's most bizarre and darkly funny moments, Magdalena sobs over her husband's affairs while randomly screaming her desire to rejoin the cause.

Yet Assayas never commits the sin of making this man truly appealing to the audience. By balancing the farce with which he plays out Carlos' actions with the irresistible performance given by Ramírez, Assayas creates a well-rounded portrait of the man, starkly capturing the hypocrisy in the Jackal's actions but not discounting some hint of idealism that must have motivated him somewhat. To further ensure the audience doesn't get too caught up in action revelry, a great deal of violence is left off-screen. While guns fire throughout the first two parts, the shootouts are anticlimactic, and late-stage violence, such as Carlos' paranoid murder of a comrade in the next room over from his sleeping baby daughter, are announced in retrospect. Assayas also uses stock news footage after a number of terrorist actions, not only to make up for some of the detail the fast-paced camerawork managed to blitzkrieg past but to offer looks at the aftermath without the allure of big-budget explosions. When Carlos bombs two TGV trains, we see the real result, twisted, collapsed metal, instead of watching the train skid off the rails over loud music.

Speaking of music, the use of post-punk songs from bands like Wire is a brilliant method the director uses for getting inside the heads not only of Carlos but some of the people around him. This is what they hear in their heads every morning when they wake up, the soundtrack to their own movie, their own

Battle of Algiers. By using post-punk instead of classic punk bands like The Clash or Crass, Assayas makes an important distinction: post-punk took the attitude of punk and, with exceptions, replaced politics with the personal, even making more socially aware tracks more intimate. Likewise, these people tend to view terrorism only through their own lens, seeing themselves as heroic for intervening on the behalf of others. If a post-punk just wanted to make music, these guys just want to make trouble. Only Nada gets an actual punk song, the Dead Boys' seminal "Sonic Reducer," and that's because she's the only one crazy and committed enough to warrant one. ("She's like the MC 5 of terrorism," Assayas hilariously but astutely notes in the aforementioned interview.)

If anyone else had been in charge of the last two hours,

Carlos might have screeched to a halt and entered stereotypically "biopic" territory. But Assayas and Ramírez are not interested in the various events that befall our protagonist but

why he lets himself fall apart.

Carlos, for its epic length, might make a number of rewarding double-bills. The first comparison is of course

Che, where one could compare Guevara's downfall in part two with Carlos' much more protracted slide into oblivion (plus, if you thought Che lost his way by sporting a Rolex, consider that Carlos buys a damn mansion). One could also pair the movie with

Munich, Steven Spielberg's even-handed look at the failures Israel's Mossad made when seeking revenge for the 1972 massacre at the Munich Olympics. Those revenge attacks provoked Carlos' own actions, and the combined sight of unforgivable mistakes made on both sides of Isreali-Palestinian situation would prevent easy alignment with either cause. I'm so used to "Based on a true story" banners at the start of films that I was amazed that Assayas, who thoroughly researched his film with greater journalistic integrity than dots most biopics, would go to painstaking lengths in an opening disclaimer to note that this is a work of fiction. Ironically, by admitting that he must lie, Assayas is more truthful to us than most, and that same contradictory honesty makes

Carlos one of the greatest films of the new millennium and a document of terrorism that can intrigue and enlighten people on both sides of the political spectrum. It also speaks to the truth hidden in plain sight in that old photograph of Carlos: look beyond that vague aura of smug cool and you'll see nothing more than a fat, smirking fool with bad taste.