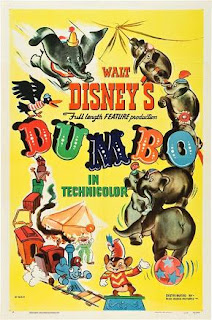

With its tight running length—barely stretching to the point of feature length—and stripped-down visual style, Dumbo broadcasts the financial desperation motivating it as if trumpeting it through the trunks of its elephants. After Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs proved one of the greatest hits in motion-picture history, Walt Disney promptly sank profits into the far more ambitious experiments of Pinocchio and Fantasia, both of which proved to be costly flops. Desperate to refill coffers, Disney took a planned short film adapting a story written for a novelty toy and had his team inflate up to a 64-minute picture to get some money, any money, back into the studio.

Yet if Dumbo is, fundamentally, a last-ditch effort to raise money, it must surely rank as one of the most delightful and genuinely creative "cash grabs" put to film. Moving away from the more detailed and expensive oil and gouache background paintings that gave Disney's previous two features their considerable artistic depth, the animation team returned to the more economical use of watercolor for backgrounds. But if the cuter, broader backgrounds lacked the intricacy of Fantasia's vastness or Pinocchio's masterfully modulated sense of scale, they also freed up the animators to focus on more vivid character animation, and one need only compare the expressiveness of Dumbo's baby blues to the more basic facial capabilities of prior characters to see how much the Nine Old Men and the rest of the animators could grow even when taking a studio-mandated step-backward.

The film's plot, even considering the running length, is spare: storks bring a circus elephant a baby boy blessed/cursed with massive ears, and the constant mocking the child receives eventually causes the mother to snap and get taken away from her boy. But this basic plot makes for a story more emotionally gripping than the previous three Disney features by leaving everything to the character animation. Mrs. Jumbo's deflated look when Dumbo does not initially come with the other delivered babies, the fat tears that roll down Dumbo's cheeks when he is ostracized for something he cannot help, the twisted looks of haughty disgust on the faces of the other elephants; all of these serve as emotional gut-punches that give much of the film a heavy sadness that conflicts wholly with the candy-colored sweetness of the backgrounds.

Dumbo himself is a masterpiece, the high- water mark of character animation in Disney's golden period and the standard to which nuanced, expressive character rendering must be judged today. The animator responsible for him was Bill Tytla, erstwhile the animator of hard-edged villains or at least antagonizing characters. He gave Grumpy his visual spikiness, Stromboli his undulating and unstable mass of flesh, and Chernobog his pants-wetting, epic-scale evil.

But Dumbo is something else entirely. Drawn with soft edges, Dumbo has just enough lines to confine him into the shape of an elephant. But the pink of his ears runs fluidly into the gray of his skin, his movement one of grace and clumsiness, the embodiment of innocence that culminates in eyes so blue they stand out even at night. Every action this poor, different creature makes is endearing, from his playful bath to inadvertently getting drunk when he drinks water mixed with champagne. Dumbo never utters a word throughout the film, and rarely makes noise of any kind, but no matter: one look at him and you're as liable to look out for him as his mother. Dumbo would be Tytla's last masterpiece for the studio, and the simple, emotional purity of the baby elephant stands as his finest achievement.

The rest of the animation is no less impressive. Woolie Reitherman handles most of the early scenes involving Timothy Mouse, the Jiminy Cricket-esque figure who looks after Dumbo in his mother's absence. These early Timothy scenes show the same attention to scale that defined Pinocchio's shifting animation, with Reitherman making tree trunks of elephants' legs and stretching the great beasts even higher as Timothy berates them for their treatment of Dumbo, the low-angle shots used to the opposite effect of their theoretical meaning: here, Timothy conveys so much of the audience's indignation that he propels his outrage upward, blowing apart the usual power dynamics of such framing. An earlier sequence of black workers and the circus animals themselves erecting the circus tent upon arriving at their destination suggests that more than one person at Disney was pleased with Sergei Eisenstein's endorsement of their work, for the sequence looks like something the Constructivist would have died to put in one of his films. As sheets of rain stab down in diagonal lines, the animals and employees raise beams and canvas. Cut corners abound in this film's animation, but the striking use of diagonals and grim light convey the energy-sapping slog of the labor. And after the animators strike that would throw off the balance not only of this film but subsequent Disney features of the decade, this sequence's depiction of race and class exploitation comes to be one of the studio's most scathing autocritiques, a depiction of the circus, the ostentatious brand of family entertainment, effectively enslaving its workers, sometimes across generations.

(This sequence, seemingly extraneous, may also have worth for clarifying the role of the crows who appear later in the film. Derided, not unfairly, as stereotypical depictions of black people, the crows indeed dress and speak in perceived black patterns, and the leader of the bunch was even named Jim Crow in script drafts. Nevertheless, as grating and dated as these visualizations are, performance-wise these characters, only one of whom is voiced by a white person, are more complex and defiant than any live-action black character at the time could ever be. Though they join in the mocking of Dumbo's ears, they direct most of their jabs at Timothy and are even stand-offish against Timothy's own forceful nature. They also prove to be the only characters besides Mrs. Jumbo and Timothy to support and encourage Dumbo, even coming up with the trick to give Dumbo confidence to fly. Their animated depiction is still troubling, but the actual behavior of the crows, combined with the earlier look at black employees visually aligned with animals as creates of hard, thankless labor for whites, suggests a rare depth for Disney.)

The best animated sequence of the film, however, is also the one that has the least to do with the overall tone of the film. Dumbo and Timothy, both drunk on the spiked water, have a joint hallucination of creepy, neon elephants dancing in the sky. The notorious Pink Elephants on Parade sequence has been lauded and dismissed for its sudden break from diegetic coherence, but it is impossible to deny the power and sinister fluidity of the animation. The nightmarish elephants move like gelatin, jiggling and stretching with abandon as they dance around a jet-black void, a void also seen in the vacant, disconcerting pits where their eyes should be. Obviously, this hallucinatory vision clashes not only with the watercolor softness of the rest of the film but with the reality of inebriation itself, yet it demonstrates one last fitful gasp of Disney's pure artistry before they began to aim in a more commercial direction. Disney films would see such a gonzo burst of neon color again until Eyvind Earle did the art direction on Sleeping Beauty.

With Dumbo, we see the emergence of Disney's patented brand of sentimentality; the studio was already upholding conservative values with Snow White and Pinocchio, but here at last one can see Disney actively targeting the audience's emotions. It proved so successful—earning more than Pinocchio and Fantasia combined at a fraction the expense—that the studio soon learned how to commercialize that appeal, and the studio never truly aimed for the loftiness of Pinocchio or Fantasia again. As such, Dumbo is a harbinger of things to come, more so because of the controversy of the strike that occurred right after completion of principal animation, which might also explain some minor hiccups throughout that didn't receive a smoothing-over. Along with Bambi, Dumbo represented the changing face of the studio and the end of its all-too-brief Golden Age; the studio wouldn't put out another feature of remotely comparable quality until the end of the decade with Cinderella (though 1944's The Three Caballeros displays some of the old ambition), and the familial atmosphere of the workplace was shattered by the strike and Walt's harsh reaction to it.

Nevertheless, Dumbo displays all of the creativity and brilliance of Disney's classic era, from its pleasing style to its emotional devastation—for my money, seeing Mrs. Jumbo confined so-close-yet-so-far-away to her lonely, mocked son and capable only of reaching out her trunk to morosely comfort him is profoundly more disturbing than the flat-out death of Bambi. It's remarkable to see how Dumbo fits in with its surrounding features, sharing the traits that run through early Disney features—the emotional shortcuts of Bambi, the overarching validation of a conservative worldview, even matching animation like Mrs. Jumbo's jail resembling the mobile one Stromboli uses to trap Pinocchio. But it also shows the stylistic variance of these early Disney movies, its watercolor softness radically different from the sharp, edgy oil and gouache of the preceding two films, the impressionistic realism of Bambi, and even the more picturesque watercolor of Snow White. Its pared-down running time makes it perhaps the most emotionally direct of Disney films, but also the one that most effortlessly pulls of its heartstring-tugging. Despite its simplicity, I would not hesitate to rank it among the studio's finest achievements, and in fact I can name no more than three or four Disney films I might find superior to it.

|

|

|

|

|

Home » Posts filed under Disney

Showing posts with label Disney. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Disney. Show all posts

Saturday, September 24

Sunday, June 26

Cars 2 (John Lasseter, 2011)

I will not ask why Cars 2 exists because I've seen the merchandising figures from the first film. Nevertheless, it's a question I couldn't force out of my mind while watching this two-hour bore. After a string of ambitious, beautiful films that established Pixar as one of the most respected studios on Earth, they finally sink to the sad state of their bosses at Disney. This isn't a film, it's a preview of coming attractions at a theme park. I didn't stay through all the credits, but I nearly did just to see if it ended with an advertisement to come check out Cars Land next year at Disney California Adventure.

I will not ask why Cars 2 exists because I've seen the merchandising figures from the first film. Nevertheless, it's a question I couldn't force out of my mind while watching this two-hour bore. After a string of ambitious, beautiful films that established Pixar as one of the most respected studios on Earth, they finally sink to the sad state of their bosses at Disney. This isn't a film, it's a preview of coming attractions at a theme park. I didn't stay through all the credits, but I nearly did just to see if it ended with an advertisement to come check out Cars Land next year at Disney California Adventure.Underlining the sheer cynicism of this film's conception is the near-total lack of characterization. John Lasseter, whose erstwhile evocation of the young, winsomely childlike George Lucas here brings out the mercenary side of the Star Wars creator, transparently structures the film to avoid personal connection in favor of selling toys. Forgettable as the first Cars was, it at least spent time with its characters; Cars 2 throttles past the drama between Lightning McQueen (Owen Wilson) and his loving but tiresome best friend Mater (Larry the Cable Guy), preferring instead to get in as many new vehicles as possible to make sure Disney's merchandise wing ends this year in the black.

For whatever reason, Cars 2 plays out both as a world-spanning Grand Prix and a spy movie, forcing incessant cuts between McQueen's unimportant exhibition match and an insultingly simplistic spy mystery that even a child could guess within the span of about 10 minutes. The two threads converge over a new alternative fuel pushed by a reformed oil tycoon (Eddie Izzard), the race sponsored by Axelrod to test and promote his new product and the spy stuff uncovering a plot by Big Oil to protect its interests. You thought the environmental message in Wall•E was on the nose? At least that was part of a beautiful and beautifully told story; here, Lasseter just ladles on some social commentary in the midst of his choppily edited action sequences.

There's something profoundly disturbing about the perception of this film as Pixar's most kid-friendly movie, considering the casual gun violence sprinkled throughout. Other Pixar movies contain danger and more ambitious ideas, but that doesn't exclude them from children. This film, on the other hand, is insipid and shiny and hollow, Pixar's first great capitulation to ADD. Because it makes no effort to get the audience to care about any character, Cars 2 can have fun with its explosions and gunfire without worrying about a child getting upset. Compare the banal "suspense" scenes of contrived danger here to the wrenching near-death of Wall•E: if Lightning McQueen suddenly contracted HIV (CIV?) I still wouldn't care about him.

Admittedly, Cars 2 has the decency to sport some of Pixar's strongest animation. Like its predecessor, the film offers the animators a chance to particularly hone their lighting work, and Cars 2 at times outstrips the look of anything the studio has done. The belched flames of oil refineries look even more real than the swirling inferno of Toy Story 3's incinerator, and the animated Tokyo might be even more dazzling than the real thing. But nothing ever wows in this movie. Whatever magic Tokyo might have held is instantly dispelled by the stereotypical humor used for cheap laughs (hahaha Japanese toilets are confusing!), while the nature of the Cars universe continues to be so vexing I can never connect with it.

Why do the cars eat when they seem to fill up like real automobiles? Who built any of this world without hands? Are the vehicles born or manufactured? (I think the answer to this one is both, depending on the setup.) And why are there shitting metal detectors in an airport? I know it's a cartoon, but that only means this childish response is all the more appropriate: I don't like this world. I don't like its meaningless, undeveloped characters. I don't like its villains all cheap models like Gremlins and Pacers, an unfunny joke period and certainly one that won't work on children. I don't like its environment, meticulously animated solely for visual and spoken puns and never given flavor and personality the way Ratatouille's Paris, Wall•E's trash-ridden Earth or the various playpens of the Toy Story movies are. And I don't like its puerile, inconsistent humor, none of which connects because the characters are so undefined they provide no anchor for the comedy.

Cars 2 wants to tread in the same waters as the first film, stressing the importance of friendship, but Pixar already developed this theme with far greater resonance in the Toy Story pictures. And with Mater jet-setting around with British spies Finn McMissile (Michael Caine, the only person even trying to give his character some flavor) and Holly Shiftwell (Emily Mortimer), Lasseter never even bothers to flesh out Mater's insecurity and hurt feelings save for clumsily inserted scenes of reflection. And don't even get me started on the rivalry between McQueen and Italian F1 racer Francesco (John Turturro), a mutual dislike so dull that the filmmakers can only hope that we care about who wins based on past familiarity with the American car.

Cars 2 will make its money, perhaps even faring a bit better overseas now that it adds more European and Asian models, but if every Pixar film sets out to prove some artistic or moral point, Cars 2's message seems to be open, cynical confirmation that the studio truly can make not merely a weak film but a dismal, greedy one. Be sure to bring a copy of your disappointment with you to California next year, everyone; you'll get a Fastpass for half price.

Posted by

wa21955

Labels:

2011,

Disney,

Eddie Izzard,

Emily Mortimer,

John Lasseter,

John Turturro,

Michael Caine,

Owen Wilson,

Pixar

Saturday, October 9

Beauty and the Beast (1991)

After spending nearly three decades in a creative wilderness, Walt Disney Pictures rebounded in 1989 with The Little Mermaid, ushering in the "Disney Renaissance," a period commonly accepted to have lasted through the release of Tarzan in 1999 (even a cynic would at least have to go as far as 1994's The Lion King). Yet nothing produced during the 10-year creative revival at the studio could match the power, beautiful simplicity and downright entertainment value of the two films that signaled Disney's return to prominence.

After spending nearly three decades in a creative wilderness, Walt Disney Pictures rebounded in 1989 with The Little Mermaid, ushering in the "Disney Renaissance," a period commonly accepted to have lasted through the release of Tarzan in 1999 (even a cynic would at least have to go as far as 1994's The Lion King). Yet nothing produced during the 10-year creative revival at the studio could match the power, beautiful simplicity and downright entertainment value of the two films that signaled Disney's return to prominence.Beauty and the Beast could easily be seen as unnecessary, what with Jean Cocteau's magical adaptation floating around the ether for some 50 years before the creative teams in Glendale, Cali. and Orlando decided to finally get the twice-abandoned adaptation of the fairy tale. Yet it marks the pinnacle of Disney's style of animated filmmaking -- Broadway one frame at a time -- creating atmospheres not only romantic and lilting but intimidating and provocative. What's more, it's damn near the most subversive thing the animation studio ever put out.

Just consider the three main characters. Belle arrives in southeastern France as the daughter of an inventor, and the village folk immediately ostracize them. It would be easy, oh so easy, to point out the reductive, facile feminism of Belle, whose greatest single attribute for the first 10 minutes or so is the fact that she reads, the sort of character trait that is as much a cheap male fantasy as any of the passive homemakers in previous Disney princess movies. Yet Belle isn't a cardboard feminist, even if her only devotion is to her father; her loyalty comes off more a result of a mutually loving and supportive bond and a reaction to her discomfort with others than a sense of duty. As she walks through the village at the start of the film, everyone fixates on her bookish nature, ignoring her attractiveness.

Ironically, the only person who does notice how beautiful she is is the most boorish and pigheaded. Gaston, a muscly, self-absorbed man who makes me want to call up my old French teacher and ask, "Comment dit-on 'juicehead?'" is the most lusted-after person in the village. He's sort of alpha male that women want to be with and men want to be (to the point that they too seem to want to be with him). Where the other villagers are so rural that they don't see the point of reading, Gaston is so utterly stupid that he can't even process anything beyond physical attractiveness.

Ironically, he's one of the most brilliant characters in Disney history, because the animators and writers use him to subvert the image of the classical Disney prince. In any other movie, Gaston would be Prince Charming, wealthy, handsome and attached to the heroine, capable of improving her station beyond her wildest dreams. Here, however, he's a misogynistic tyrant who decides to marry Belle simply because she's the prettiest around and refuses to hear her opinion in the matter. Clearly, he's never not gotten his way, and Belle's polite but firm rejection is a threat to his masculinity that drives him to a murderous rage. What initial attractiveness the man might have is almost immediately dispelled by his nature, and there can be no mistaking his role as the film's villain.

Compared with the Beast, Gaston's rotted personality could set up an "inner beauty" fable on the level of Shallow Hal's fatuous nonsense. But that ignores the Beast's initial nature: he's as vile as Gaston, and his curse stems from his egotistical demeanor. There is no preferable choice for Belle's affections at the start, because she does not exist simply to give them away. She is not looking for love at all, only traveling to the Beast's castle because the monster holds her father prisoner. She asks to take her dad's place because she's young enough to spend time in a dusty, cold castle.

Fundamentally, that's the beauty of Beauty and the Beast. Rather than tell a story about separated soulmates (Snow White, Sleeping Beauty, many, many more), the writers create a fairy tale that uses the fantastical elements of a castle populated by anthropomorphized objects and ruled by a demon lion/dog to tell a realistic love story. To be sure, the conceit of two antagonistic forces learning to love each other is a dead horse of a different color, but the characters don't fully realize their feelings until the last 10 minutes. Instead, Beauty and the Beast first plays as Pygmalion in reverse, a beautiful, refined woman breaking through the crude manners of a beastly male to bring out his gentler side. Only when the Beast finally ceases thinking of himself does he understand the feelings that nag at him for an hour.

From an animation standpoint, Beauty and the Beast does not quite measure up to its storytelling standard. Now, it does not want for visual imagination: rich colors and enticingly rendered characters bump against the emerging Computer Animation Production System used to handle backgrounds. CAPS allows animators to pull of shots that simply could not be done by hand, from rapidly canting angles of simulated motion to the majesty of the film's centerpiece, the ballroom dance set to the titular song.

The problem arises from time and budget constraints. Two months before the film premiered, the animators sent a workprint version to the New York Film Festival. However, that version had only 70% of the final footage, and one can see the two months' worth of cramming at times. Occasionally, secondary characters lack expressive animation, and backgrounds lose their detail in spots. When the CAPS animation sometimes jars with the 2D rendering, I can't help but wonder whether technological limitations or time issues are to blame.

What cannot be criticized, however, is the drawing of the main characters. Mark Henn, who would go on to make most of the best-drawn female characters in Disney history (he'd already co-drawn Ariel), makes Belle into someone who clearly grew up reading instead of doing chores, but she looks more ready for something bad to happen than Cinderella. And when he puts her in that yellow dress, he crafts the most stunning Disney princess since Aurora. Andreas Deja gives Gaston such a predatory stalk and evil leer that the animator clearly intends older viewers to identify a rapist mentality driving the character. It's not so explicit that children will either fail to understand Gaston's evil and thus lose interest or be scarred, but for once the creepy nature of a strapping man in a Disney film is intentional.

But nothing compares to Glen Keane's animation of the Beast. His finest creation, the Beast is first introduced in silhouette, taking on the likeness of the great demon Chernabog from Fantasia. In light, he resembles a hybrid of a lion and a wolf with demonic horns, capable of conveying terrifying, unstoppable animal force when on all fours and a comical yet believable humanity when he straightens his back. Almost as if to prove how great Keane is, the film positions the two ways of animating the Beast one almost immediately after the other (from Beast fighting off wolves to him making a buffoon out of himself learning etiquette) to demonstrate how fluidly Keane can transition between the two depictions.

The single greatest aspect of the entire film, however, more than the storytelling, more than the lead animation, is the songwriting. Howard Ashman revived Disney's tradition for great, memorable songwriting with The Little Mermaid, and his work is likely as big a reason that film succeeded and revived the studio's creative legacy as anything in the movie. Here, he ups the ante: with Alan Menken, Ashman crafts perhaps the greatest songbook to accompany a Disney film, and one of the best of any film of any kind. There are individual songs to match the hits here, from "When You Wish Upon a Star" to "Once Upon a Dream," but there isn't a single song that feels like a filler. Hell, I'm struggling to think of another Disney film that uses its songs so brilliantly not simply to adds some spice to the proceedings to but advance both narrative and character. Ashman's deliciously simple titles seem like afterthoughts but simply convey the essence of each song. "Belle" opens the film in pure opulence, creating a wave of cascading voices, some of which join into harmonies, others directly oppose one another. The effect perfectly establishes the character, whose lines are always sung the most softly and without anyone else joining in. "Gaston," meanwhile, inverts this, making the lines of all the other villagers hang off his every rhyme. "Be Our Guest" makes the opening seem tame in comparison, yet its explosion of extravagance is every bit as justifiable as "Belle": like that song, "Be Our Guest" establishes character in the midst of effervescent songwriting. The residents of the castle are all servants turned into the object they controlled, and they're thrilled to finally have a guest to wait upon once more. They are the ultimate depictions of existentialism, having literally become their jobs, so the opportunity to perform their duties simultaneously makes them feel alive once more.

As for the aforementioned title track, well, only "When You Wish Upon a Star" could possibly challenge it in my book, and I might still side with this. Sung in Angela Lansberry's beautifully soaring voice, "Beauty and the Beast" encapsulates the entire film's thoughtfulness on love, something that doesn't exist in fairy tales but in life; it's just harder to see out here. By my count, the song contains only 29 lines (including repeated ones), and all of them make an impact. "Barely even friends/Then somebody bends/Unexpectedly" starts the first stanza in earnest, and the subtlety of it has the ironic effect of being overpowering. Instead of making grandiose proclamations of destined love, Ashman goes for the truth, which is so much more romantic and rewarding: we don't know we're in love until we spend time with someone and unforced adjustments make the pieces fall into place.

Ashman died from complications from AIDS just before the film premiered, and he is beautifully (and rightly) eulogized in the credits as the man "who gave a mermaid her voice and a beast his soul," and while Disney would make a number of fantastic films through the end of the century, Ashman's death left a hole that even the best of them couldn't fill.

Beauty and the Beast opens on a familiar sight in Disney fairy tale fiction: still images of folkloric artwork as a narrator introduces the tale. Yet compared to the storybooks of old, the animators treat us to depictions of the background on stained glass, suggesting either that this really happened or, like religious stories, it is such an inspirational tale that it deserves to be remembered even if you don't believe it. I still must choose Pinocchio for the agelessness of its dynamic vision, but Beauty and the Beast marks the pinnacle of Disney's work with fairy tales, and it's a shame Walt Disney couldn't have lived to see the purest example of what he wanted from his studio.

[Beauty and the Beast is now available on a stunning Blu-Ray from Disney. Picture and audio quality put to shame even other Disney restorations such as their sterling work on Pinocchio and Sleeping Beauty. I cannot urge purchasing it enough.]