By virtue of their outlandish style, Johnnie To’s films often broach the postmodern and Brechtian even at their most straightforward; think the opening gunfight of Exiled, in which the sight of a door being suspended and even pushed back and forth in midair is both a source of hilarious cognitive dissonance and the oddly logical climax of the sequence. Romancing in Thin Air, though, features the director at his most nuanced and subtle, stylistically grounding the film so that the many flourishes become not par for the course but formal means of breaking down distinctions between art and life.

If the film ultimately erodes such barriers, however, it opens with a clear delineation of reality from artifice. With HDTVs now offering a home cinema experience even for news shows, To pointedly uses analog, full-frame TVs to show actor Michael Lau (Louis Koo) winning Best Actor at the Hong Kong Film Awards and proposing to his actress girlfriend, Yuan Yuan (Yuanyuan Gao), then being stood up on his wedding day when her first love (a coal miner) turns up out of the blue and wins her back. The farcical turn of events plays out in a constricted frame on old, standard-definition video quality, marking it as something false. But then, what To shows is gossip, the world of celebrity, which belongs neither to the real world outside privileged circles nor to the art that is corrupted by it. But even this aesthetically separated realm is complicated when Michael, driven to alcoholism and ruin, is expelled from the television into the world, the final indignity of the fallen star.

Michael stumbles into the back of a truck and comes to in Shangri-La. No, really. The driver of the truck, Sue (Sammi Cheng), watched Michael’s antics on TV before heading back to the countryside, and when she arrives back at the inn she owns, her co-workers, rabid fans of Michael’s who sob at what has become of him, turn apoplectic when they see her truck in the background of some tabloid footage of Michael. In a small way, the garishness of celebrity press claims a piece of the real world. Eventually, Michael gets out of the car and wanders into the hotel, where Sue catches him playing a piano. Her puzzling reaction, a cautious recognition not of the actor but of someone she knows, sets the film’s deeper explorations into motion.

As it happens, Michael’s piano playing reminded Sue of her husband, Tian, who went missing seven years ago. Flashbacks reveal that Tian was the original innkeeper, a shy man who fell in love with Sue when she would vacation there as a student. Heretofore the only person who treats Michael as the sad human being he has become rather than the heartthrob who sends the other women into frenzies, Sue is shown in the flashbacks to be just as giddily enthusiastic about Michael as her co-workers in the present, and is even a member of Michael’s fan club. To woo her, Tian apes elements of Michael’s films, from motorcycle riding to playing the piano theme Michael composed for a movie. Art adapts life to its purposes, but here, life reworks art to its own.

This makes a warped love triangle between the missing husband, his loyal wife and the star who unknowingly brought them together and now matters to the former superfan less for his own presence than the connection he provides back to the lover who mimicked him. This complicates melodramatic cliché across metaphysical levels, introducing a troubling element to Michael’s rehabilitation and growing relationship with Sue that is further compounded when the man who appropriated Michael’s art to communicate how he felt about Sue subsequently becomes fodder for a film Michael makes with the same intentions.

To fully explore the depths To wrings out of this material would divulge too much of the story and the way it constantly offers surprises despite following a broad genre formula. To’s capacity for visual storytelling is almost unmatched by any contemporary filmmaker, and various shots speak to the slow blending of realities as well as the larger arcs. To establishes Shangri-La with sweeping, naturalistic panoramas, but as Michael and Sue’s interactions become more cinematic, the mise-en-scène grows more stylized. When their nurse-patient relationship inverts in a scene of Michael toting a drunken and despondent Sue through the snow, the sadness of the moment is magnified by the way To and cinematographer Cheng Siu-keng dampen down the forest, removing the twinkle of light on snow that looks so dull and still that the deadness around the characters resembles nuclear winter rather than the seasonal kind. Later, Michael takes Sue to see a film that eerily parallels how Sue lost Tian and how she struggles to let go of him. In one of the film’s most striking shots, the pair sit in the foreground, their heads far enough apart for the space in-between to be filled by the shot on-screen in the film within the film, a close-up of the Sue-esque figure finally removing her wedding ring. The meaning is clear, but the beauty and anguish of the shot overpower its symbolic obviousness, the heady, metaphysical dimensions of the film linked by raw human emotions of grief, desire and coping.

The moment also captures the tonal midpoint Romancing in Thin Air achieves between its affectionate attitude toward how even the lightest piece of populist fluff can speak trigger real feelings and the darker manipulation, even exploitation inherent in art’s relationship to life. The cinema of 2012 has been obsessed with the supposed end of the world, or at least cinema. To's film sidesteps such hyperbolic terms and therefore can grapple with nuanced complexities. As such, Romancing in Thin Air manages to probe the tangible discomforts of its subject matter, wrap them in the dual obsolescences of the melodrama genre and the notion of the remote, rustic countryside as the ideal real world getaway, and emerge with something that proves the enduring vitality and richness of what is being mourned elsewhere this year.

|

|

|

|

|

Home » Posts filed under Johnnie To

Showing posts with label Johnnie To. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Johnnie To. Show all posts

Wednesday, November 28

Tuesday, November 27

Capsule Reviews: Beasts of the Southern Wild, Life Without Principle, On the Road

Beasts of the Southern Wild (Benh Zeitlin, 2012)

Benh Zeitlin’s debut feature, Beasts of the Southern Wild, uses memories of Katrina as fodder for a sub-magical-realist burst of half-stylized poverty porn. Zeitlin aims for inoffensiveness by casting the severe limitations the poor face—no access to healthcare, poor education, the laughably weak safety net—as fantastical positives. This is a film where witch doctors brew medicine in jars, where everyone looks freshly rubbed down in dirt to achieve just the right look of want, and where only the truly worthy both refuse to evacuate from a coming storm and violently reject any attempts by outside bodies to help them. Young Quevenzhané Wallis and Dwight Henry give performances entirely too good and revelatory for such heinous rot, but even their raw and honest work is undone by the falsity of what they are meant to invoke. Like Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, the film approaches a serious, national trauma and filters it through the eyes of a child. And like that other disaster, it does not use this perspective to grapple with the scope of tragedy but to infantilize it. Grade: D-

Life Without Principle (Johnnie To, 2012)

Life Without Principle cuts against the grain of financial crisis movies that take place behind solid, wooden doors, instead curving around the public floor of the bank, where employees are watched through their transparent barriers to provoke them into selling more, always more. It also moves among those unconnected to the financial industry save the shackles they place on themselves to pay for their lifestyles, linking not only the benign social climbers reaching beyond their grasp but the criminal element who come off as farcically sloppy compared to the machinations of the banks. By keeping his camera street-level, To can approach the tangled web of culpability with empathy and admonishment without the saccharine crucifixion of the fatcats who set the collapse into motion. We do not even have to sit through yet another portentous realization that the market will crash; it simply does one day, and we know about it because the financial analyst struggling to make her quota suddenly fields dozens of frantic, furious calls from people watching their life savings disappear. Movies like Arbitrage spare false sympathies for those who had every indication of what was coming but kept ignoring it, but Life Without Principle truly captures the sudden upheaval experienced by those who subconsciously put their faith in the system, and the coldness of that faceless, inhuman greed hangs over the proceedings. Even its resolution, a triumph on material grounds, reflects the amoral, arbitrary meaninglessness of a world in which the vagaries of monetary value hold sway. Grade: A-

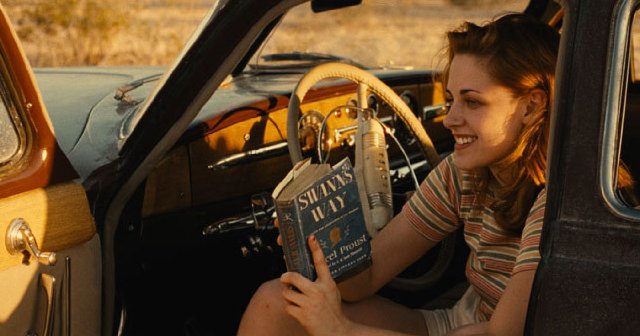

On the Road (Walter Salles, 2012)

Shot as if making a teen film set in the present, On the Road divorces the Beats first of aesthetic, then social context. Salles’ film portrays the characters as the sort of listless creatures who populate our current movies, youth in medicated, dead-eyed search for a cause, rather than having a plethora of choices at their disposal. Drug use, sexual experimentation and jazz run through the film as they did the book, but there is no element of transgression to the behavior, no feeling that they are doing something wild. So interminably dull, even repellent, are the characters and their journey to nowhere that, for a brief spell, I began to hope the film would undermine and critique the solipsistic Beat escapism on display, with privileged white youth rebelling against a society that affords them such comfort that they can do as they please while others must toil. But no, there is a terrible earnestness to the self-evidently awful lives inflicted on an entire nation as the road carries the characters back and forth. So maybe it’s a faithful adaptation, after all. Grade: D

Benh Zeitlin’s debut feature, Beasts of the Southern Wild, uses memories of Katrina as fodder for a sub-magical-realist burst of half-stylized poverty porn. Zeitlin aims for inoffensiveness by casting the severe limitations the poor face—no access to healthcare, poor education, the laughably weak safety net—as fantastical positives. This is a film where witch doctors brew medicine in jars, where everyone looks freshly rubbed down in dirt to achieve just the right look of want, and where only the truly worthy both refuse to evacuate from a coming storm and violently reject any attempts by outside bodies to help them. Young Quevenzhané Wallis and Dwight Henry give performances entirely too good and revelatory for such heinous rot, but even their raw and honest work is undone by the falsity of what they are meant to invoke. Like Extremely Loud and Incredibly Close, the film approaches a serious, national trauma and filters it through the eyes of a child. And like that other disaster, it does not use this perspective to grapple with the scope of tragedy but to infantilize it. Grade: D-

Life Without Principle (Johnnie To, 2012)

Life Without Principle cuts against the grain of financial crisis movies that take place behind solid, wooden doors, instead curving around the public floor of the bank, where employees are watched through their transparent barriers to provoke them into selling more, always more. It also moves among those unconnected to the financial industry save the shackles they place on themselves to pay for their lifestyles, linking not only the benign social climbers reaching beyond their grasp but the criminal element who come off as farcically sloppy compared to the machinations of the banks. By keeping his camera street-level, To can approach the tangled web of culpability with empathy and admonishment without the saccharine crucifixion of the fatcats who set the collapse into motion. We do not even have to sit through yet another portentous realization that the market will crash; it simply does one day, and we know about it because the financial analyst struggling to make her quota suddenly fields dozens of frantic, furious calls from people watching their life savings disappear. Movies like Arbitrage spare false sympathies for those who had every indication of what was coming but kept ignoring it, but Life Without Principle truly captures the sudden upheaval experienced by those who subconsciously put their faith in the system, and the coldness of that faceless, inhuman greed hangs over the proceedings. Even its resolution, a triumph on material grounds, reflects the amoral, arbitrary meaninglessness of a world in which the vagaries of monetary value hold sway. Grade: A-

On the Road (Walter Salles, 2012)

Shot as if making a teen film set in the present, On the Road divorces the Beats first of aesthetic, then social context. Salles’ film portrays the characters as the sort of listless creatures who populate our current movies, youth in medicated, dead-eyed search for a cause, rather than having a plethora of choices at their disposal. Drug use, sexual experimentation and jazz run through the film as they did the book, but there is no element of transgression to the behavior, no feeling that they are doing something wild. So interminably dull, even repellent, are the characters and their journey to nowhere that, for a brief spell, I began to hope the film would undermine and critique the solipsistic Beat escapism on display, with privileged white youth rebelling against a society that affords them such comfort that they can do as they please while others must toil. But no, there is a terrible earnestness to the self-evidently awful lives inflicted on an entire nation as the road carries the characters back and forth. So maybe it’s a faithful adaptation, after all. Grade: D

Posted by

wa21955

Labels:

2012,

Benh Zeitlin,

capsule reviews,

Garrett Hedlund,

Johnnie To,

Kristen Stewart,

Sam Riley,

Walter Salles

Sunday, August 14

Capsule Reviews: Platinum Blonde, The Mad Monk, The Lodger

Platinum Blonde (Frank Capra, 1931)

Now this is more like it. Capra gets it all together with a rip-snorting good time with newspaper idealism, dialogue you just wanna tap with a spoon and peel, and sentimentality that works instead of hinders. Robert Williams is more flirty than Jean Harlow (hilariously playing the straight role as the starched, bossy heiress), and the gender-reversed Pygmalion structure makes for some great comedy with the Eliza in this case being a properly snappy, streetwise paper hack. Not to mention, his gender makes for more interesting resistance to change, as Capra shows how a man reacts to being the less prominent member of a pair and the one actively being molded. Granted, it also encourages the audience to cheer when he demands chauvinistic things like his rich wife taking his name, but this is still a fascinating inversion at times. Also a delight is Louise Closser Hale as the aristocratic matriarch with her affected voice and constant, faint-headed outrage at scandal that truly no one with anything to do cares about. My distrust of Capra has always been balanced by my true admiration for him when he clicks, and this is Capra firing on all cylinders. Grade: A

The Mad Monk (Johnnie To, 1993)

A deliriously ludicrous comedy that has more fun with Eastern religion than an American genre film could ever hope to have with Christianity, The Mad Monk opens in a heaven where the head god has to deal with so many deities he doesn't recognize all of them and only gets odder from there. The Mad Monk tasks a prankster god with altering the life(s) paths of three archetypal individuals with only a trick fan for powers, leading to a whimsically ridiculous farce that To directs to a frenzy. Everything in this movie is funny; To even steps on an emotional death scene by having our Lo Han (played by Stephen Chow) burst into the wrong room (and an embarrassing bit of sexual play) as he hunts for his felled mark. With To's manic camera movement and cutting, inventively staged comic fight scenes and a climax that moves from a kaiju battle with a giant demon to a piss-take on pageantry with a heavenly promotion complete with tiara, The Mad Monk is a bewildering, side-hurting riot. Grade: B

The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (Alfred Hitchcock, 1927)

This thrilling silent, Hitchcock's fifth feature, while still a bit stiff in the narrative department, shows Hitchcock's rapidly developing talent as a director and his seemingly innate control of the camera and the Expressionistic techniques he observed in Germany. It's somewhat amusing that he still finds a way to be expository in a silent film, using multiple news stories to get across developments in the murder mystery. A 'wrong man' narrative involving murdered blondes, pained romances and the suggestion that a slit throat might always be just around the corner, this almost feels like a preemptive tribute to Hitchcock than an early work. This is a fun showcase for a man whom one can tell even here would deserve the title of "master" thrust upon him, from the use of a glass floor for Hitchcock to stick a camera under to a perfectly framed shot looking straight down a staircase as a man obscured by angle and his black clothes runs down the stairs with his sliding hand as the chief guide to his position. A real treat. Grade: A-

Now this is more like it. Capra gets it all together with a rip-snorting good time with newspaper idealism, dialogue you just wanna tap with a spoon and peel, and sentimentality that works instead of hinders. Robert Williams is more flirty than Jean Harlow (hilariously playing the straight role as the starched, bossy heiress), and the gender-reversed Pygmalion structure makes for some great comedy with the Eliza in this case being a properly snappy, streetwise paper hack. Not to mention, his gender makes for more interesting resistance to change, as Capra shows how a man reacts to being the less prominent member of a pair and the one actively being molded. Granted, it also encourages the audience to cheer when he demands chauvinistic things like his rich wife taking his name, but this is still a fascinating inversion at times. Also a delight is Louise Closser Hale as the aristocratic matriarch with her affected voice and constant, faint-headed outrage at scandal that truly no one with anything to do cares about. My distrust of Capra has always been balanced by my true admiration for him when he clicks, and this is Capra firing on all cylinders. Grade: A

The Mad Monk (Johnnie To, 1993)

A deliriously ludicrous comedy that has more fun with Eastern religion than an American genre film could ever hope to have with Christianity, The Mad Monk opens in a heaven where the head god has to deal with so many deities he doesn't recognize all of them and only gets odder from there. The Mad Monk tasks a prankster god with altering the life(s) paths of three archetypal individuals with only a trick fan for powers, leading to a whimsically ridiculous farce that To directs to a frenzy. Everything in this movie is funny; To even steps on an emotional death scene by having our Lo Han (played by Stephen Chow) burst into the wrong room (and an embarrassing bit of sexual play) as he hunts for his felled mark. With To's manic camera movement and cutting, inventively staged comic fight scenes and a climax that moves from a kaiju battle with a giant demon to a piss-take on pageantry with a heavenly promotion complete with tiara, The Mad Monk is a bewildering, side-hurting riot. Grade: B

The Lodger: A Story of the London Fog (Alfred Hitchcock, 1927)

This thrilling silent, Hitchcock's fifth feature, while still a bit stiff in the narrative department, shows Hitchcock's rapidly developing talent as a director and his seemingly innate control of the camera and the Expressionistic techniques he observed in Germany. It's somewhat amusing that he still finds a way to be expository in a silent film, using multiple news stories to get across developments in the murder mystery. A 'wrong man' narrative involving murdered blondes, pained romances and the suggestion that a slit throat might always be just around the corner, this almost feels like a preemptive tribute to Hitchcock than an early work. This is a fun showcase for a man whom one can tell even here would deserve the title of "master" thrust upon him, from the use of a glass floor for Hitchcock to stick a camera under to a perfectly framed shot looking straight down a staircase as a man obscured by angle and his black clothes runs down the stairs with his sliding hand as the chief guide to his position. A real treat. Grade: A-

Sunday, October 24

Mad Detective

Johnnie To's Mad Detective is one of the most deliberately complicated police procedurals I've seen in some time. As an introduction to the wild Hong Kong auteur's canon, it can be a bewildering experience, but a rewarding one, allowing this writer to get at the heart of what makes To stand out from other genre filmmakers working today.

Johnnie To's Mad Detective is one of the most deliberately complicated police procedurals I've seen in some time. As an introduction to the wild Hong Kong auteur's canon, it can be a bewildering experience, but a rewarding one, allowing this writer to get at the heart of what makes To stand out from other genre filmmakers working today.The first thing you notice is the camerawork. To has found a committed fan in David Bordwell, perhaps the most knowledgeable man in the world on the subject of mise-en-scène and the meaning of a shot, and one can see why instantly: setting up what might be a usual pairing of mismatched cops, the camera instead instantly subverts expectations. It moves with a fluid grace as it tracks over the sight of an older detective with a knife readied for a fight, only to reveal a swinging pig carcass that he stabs repeatedly to mimic a killer's attack. The camera cuts to reveal the previous moment to be a POV shot as a young cop, Detective Ho Ka-On enters the room to find the other cops staring at the spectacle.

Before five minutes have elapsed, To has taken the formula and muddied it, opening with those cliché establishing shots of a precinct and the rookie entering before splitting attention between objective and subjective shots. The only thing the audience can trust so far is the printing on the Kowloon District door: everything else already carries the possibility of fabrication. We subsequently learn that the older detective, Bun, stabs the pig and mimics another crime -- having Ho place him in a suitcase and throw him down some stairs -- because he is psychic and recreating the scenarios allows him to see what happened. This just opens the can of worms.

The entire department admires Bun, to the point that no one ever bothers to question how he can see people's inner selves. But they also fear his mental imbalance, and when he offers his retiring captain his own right ear as a "present," the rest of the precinct makes the not altogether unwise decision to send Bun to pasture as well. Only years later, when a cop, Wong, goes missing and his gun shows up in the use of deadly robberies does Ho go looking for the mad detective to get to the bottom of the crimes

What is also remarkable about Mad Detective is the emotional range it conveys. To juggles broad comedy, suspense, tragedy and cerebral psychological thriller deftly, and if the film is inconsistent in tone, as I have heard some say, that can only be because, for all the supernatural elements of the film, it is one of the few cop films to express any kind of believable emotion. And if emotion is believable and human, it is always complicated and conflicting.

Paired up once more with his writing partner, Wai Ka-Fei, To delights in poking fun at cop clichés without making an outright comedy. Where most buddy cop films pair a reckless rookie with a wizened old detective, To's film gives us two totally unique characters. The older cop is the crazy one, and the young one isn't particularly ambitious or adept. Late in the film, Bun sees Ho's inner personality, a frightened, insecure child whose angry front cannot remotely disguise his fear.

To's constant leap through perspectives brings out the complexity in Bun and the way he sees the world. He lives with his imaginary wife after his real spouse left him, and it's heartbreaking when the camera cuts from seeing her interacting with Bun to a more objective angle that shows a desperate man trying to keep up appearances. Perhaps the most memorable scene in the film has nothing to do with the corkscrewing narrative but an aside that shows Bun inviting Ho and his girlfriend to dinner, complete with Bun's "wife." Ho's girlfriend cannot take the absurdity and hides in the bathroom, but a sympathetic Ho makes a noble go of it, and the moment is surprisingly sweet. It's the one coherent bit of Mad Detective, and it's more affecting than the forced moments one expects of such thrillers.

Elsewhere, though, this is a pure exercise in style, and To's style is boundless. Wong's partner, Chi-Wai, is the culprit behind Wong's disappearance, and Bun sees seven distinct beings when he looks at Chi-Wai's inner personality, a person for each deadly sin and for major body parts. In the climactic shootout, the camera tracks through a hall of mirrors, alternating fluidly between objective shots of Chi-Wai moving through the room and subjective views of seven characters crowded around the one of them with the gun. Best of all is an overhead crane shot capturing shot and shattered mirrors on the ground reflecting the characters.

Mad Detective revolves around the MacGufffin of gun ownership. Chi-Wai got his gun stolen by an Indian thief, so he killed his partner and took his gun. When Bun heads out into the woods to recreate Wong's death, he confronts a spiritual vision of Chi-Wai, embodying the lost gun, taking the existential threads of a cop's badge and gun to an extreme, literal level. In the aftermath of the final showdown, the camera pulls back into full objectivity as the story moves into its most subjective and surreal moment, with guns changing hands so investigators will have an entirely different story than what we saw. I'm reminded of the climax of the Harry Potter series, which hinged on ideas of wand ownership, but To's film is sly and deconstructive where Rowling's ending was obtuse and clumsy.

"B-movie" continues to be used as a derogatory term, even a half-century after the director/critics at Cahiers du Cinéma proved that B-movies contained more ingenuity than the lavish prestige pictures, and Johnnie To may well be the filmmaker most qualified to continue demonstrating this today. Mad Detective is an off-the-wall cascade of pleasurable but conflicting elements that work only because they are unified by To's elegant style. Praise should also go to Sean Lau as Detective Bun: since his first acting nomination at the Hong Kong Film Awards in 1995, Lau has received nine more in the last 15 years. He flawlessly embraces the absurdities and the severity of the script, crafting one of the most unique characters in modern film in a performance that would be worth repeat viewings even if everything around him was mediocre. Lucky for us, it's all great. I'm routinely inspired by Asian cinema's capacity for aesthetic beauty and emotional and thematic power, but sometimes I forget how entertaining the industry can be as well. Johnnie To reminds me.