I never got around to this in my De Palma retrospective, so when Spectrum Culture decided to do one of its own, I knew I had to cover it. The results are...middling, like so many early De Palma efforts, though as a concentrated experiment in sustained split-screen usage it remains an intriguing work. De Palma's highly cinematic techniques ironically enhance the theatricality of the filmed performance, though soon he would be employing the methods for even more lavishly stylized effect. Nothing more than a curio, perhaps, but De Palma has made far worse.

My full review is up now at Spectrum Culture.

|

|

|

|

|

Home » Posts filed under Brian De Palma

Showing posts with label Brian De Palma. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Brian De Palma. Show all posts

Friday, November 16

Tuesday, February 28

Brian De Palma: Redacted

The mainstream view of Brian De Palma's 2000s output is anything but flattering, with all four of his films made in the new millennium bowing to intense critical pans and commercial indifference. However, I've found his contemporary work to rank among his best. Mission to Mars captures the boundless enthusiasm (and unabashed cheesiness) of old Disney space adventures, shot to favor near-poetry over scientific accuracy and all the better for it. Femme Fatale threw people with its narrative mulligan, but it made the strongest case to date for the director's actual feelings for women, which are far more complex than the lazy accusations of misogyny that have dogged him for so long. The Black Dahlia is, if anything, the only one of De Palma's films that can even stand with Carlito's Way in terms of sheer aesthetic and Romantic beauty. Its sloppy elements and awkward acting choices only add to its deliberate, yet gentle, attack on Hollywood. It may also be the most neatly contextualized of De Palma's films in his strange canon, fitting neatly with the more formal, big-budget experiments and the uncompromising anti-mainstream tone of his '70s and '80s work.

Then there's Redacted. In 1989, De Palma made Casualties of War, one of his most sincere films and perhaps the only one to lack any postmodern flourishes. Redacted seeks to rectify this: it swaps Vietnam for Iraq and swaps the classical filmmaking of Casualties for a collage of styles and media. De Palma constructs his film as a hodgepodge of footage sources. The intent is clear: by stylistically and narratively repurposing Casulaties' true story of a rape and massacre being arduously brought to light, Redacted uses its own dramatization of real events to demonstrate that, in a war that can now be documented by anyone with a cell phone, truth has never been further from the public's grasp. If Casualties of War found worth, even moral victory in doing the right thing, Redacted nihilistically sees no point in even trying.

For that very reason, all the incisive ideas percolating through Redacted's slim running time cannot prevent it from being one of the most abysmal, unbearable movies De Palma ever made, ranking among the dregs with Bonfire of the Vanities and Wise Guys. It's a shame, too, for Redacted occasionally flirts with greatness, suggesting a vicious assault on oblivious American mindsets since the "Be Black, Baby" segment of Hi, Mom! But from the first moments, one can tell that Redacted will be a miserable chore, not a galvanizing screed.

The film follows a company of soldiers stationed in Iraq, where they already chafe under the hot desert sun and tense relations with the indigenous population. One soldier, Angel Salazar (Izzy Diaz), decides to film life on the base, believing that his work will get him into film school when he goes home. There's a grim irony to this thought process, the home videos a young Steven Spielberg used to make where he and his friends reenacted war now replaced by a taping of a real one. But his journal reveals the first, and deadliest, flaw of the movie: Salazar, and his comrades, could not be more simplistically written or agonizingly two-dimensional. To a T, they make casually racist comments about Iraqis and show no remorse for their lethal screw-ups. A green soldier ends up killing a woman at a checkpoint when her car speeds through, and not only does he not struggle with it, he brags into Salazar's camera.

Only Salazar and another soldier, Lawyer McCoy (Rob Devaney), ever even hint at a basic humanity, and they are no more nuanced than their rapacious brethren. They are moral simply because the script calls for someone to be at least partially decent, and their protests to increasingly horrific behavior have all the conviction of a bored high-schooler forced to read a play aloud in class and doing so with a flat, get-it-over-with monotone. The squad leads a raid on a local home that they suspect contains intel, where they arrest a man for no reason as a reporter for an Al-Jazeera-like news organization asks the soldiers what they are doing. Later, some of the soldiers decide to return to have their way with a 15-year-old girl they saw in the house, killing her and her family in the process. Salazar is forced to witness it, and a protesting McCoy is thrown out by his comrades at gunpoint.

That's the basic gist of the story, but De Palma tries to dress it up with his use of multiple styles. Unfortunately, the result is an interminable mess. De Palma's asides with a group of French documentarians parody stuffy, emptily moralistic war docs, the camera slowly zooming in and out on soldiers' faces as the orchestral arrangement of "Sarabande" from Barry Lyndon plays. At least, I assume it's a parody; these segments are so tedious that De Palma must be making fun of such films, but his target is unclear. Likewise, we see various YouTube clips of terrorists sneaking bombs under the clueless eyes of the Americans, or of newscasts showing angry Iraqis swearing vengeance for what has happened to them. Everyone knows what the Americans are doing, but no one will listen.

It might be an compelling array of conflicting, yet harmonious, elements were the transitions not so jarring, the morals not so disgustingly black-and-white, and the judgment not so haughty. Casualties of War grounded its characters' sadism in an understanding for their predicament. It vigorously condemned the actions of the soldiers, but it could also at least see how they were driven to the point of feral madness. Redacted feels like an old man's rant about "kids these days," only the kids here murder a family in cold blood and set fire to a teenager after raping her. It just accepts the horror of the soldiers' actions as a foregone conclusion. Salazar blanches at the atrocity, but he also wants to reveal the truth in a way that will make his film project a hit; better to get back home and piece together a dynamite cut than get justice now. And all McCoy can do is feel bad, even up to his last moment on-screen, which openly mocks him.

War is unpleasant, and the Iraq War more unpleasant than most, given its falsified justification and mismanagement. But De Palma's usual talent for immersion in seediness fails him here. He does not capture the repulsion of war; he only makes a repulsive film. As if to ward off the pointlessness of the exercise, De Palma has his characters occasionally spout aesthetic maxims. When Salazar jokingly tells McCoy that his camera doesn't lie, McCoy replies, "That's bullshit because that's all that camera ever does." Later, Salazar more insistently urges, "Just because you watch it doesn't mean you're not a part of it." Naturally, both of these utterances are key positions of De Palma's entire approach and philosophy, but so hear them said aloud here cheapens them. Especially the latter quote; De Palma is a master of implicating his audience, up there with Alfred Hitchcock and Michael Haneke. But this film does not implicate anyone because it is so morally rigid. Casualties of War shows a situation slowly spiraling off its axis until the breaking point isn't visible. These men broke before they even left home. What, then, can we learn of them?

And why is the movie so unsparing? As with the Incident on Hill 192, the real-life Mahmudiyah killings were punished. In fact, they were punished far more severely than the incident that spawned Casualties of War. The soldiers who raped the Vietnamese girl and destroyed her village had their sentences drastically reduced, and in some cases dropped entirely. The three soldiers involved in Mahmudiyah, however, have received multiple life sentences. To end the film on an uncertain note is just bullshit posturing, an offensive recalibration of reality to fit a tidy, repellent premise. The problem with this film is that De Palma, though still a provocateur, cannot now conjure the same anarchist energy of his earliest days. When he inserts an embarrassing YouTube rant by a single-minded teenage liberal, he does not broaden the scope of his critique of contemporary culture. He merely chucks in one more stereotype to be lazily jabbed, nothing more than the wink of a shock comic grown too old.

There are so many good ideas in Redacted. The fat soldier's first raid through the house borders on the Orwellian as he seizes documents he cannot read for evidence so that he can give them to a translator to determine if they are actually evidence. The blood stains left by the dead recall those thick lines of permanent marker blacking out sensitive information, erasing the full detail of the person who was there while still leaving an unmistakable trace of malfeasance. The cross-format collage of video sources presages Film Socialisme in a Derridean attempt to chase truth through the multitude of options now available to us and coming up shorter than ever. But the lapse of De Palma's subtlety results in a film that feels like a repository for every charge ever leveled against him, from misogyny to cheap cynicism to hollow rip-offs (the music lift from Barry Lyndon and a recreation of the scorpion and ants shot from The Wild Bunch add nothing). Many of De Palma's films have vile traits, but they are usually intentionally added, well-illustrated travesties cleverly dismantled by De Palma, who can be in the thick of it and above it all at once. This, however, is the only one of his films I've ever found truly disgusting, and I hope that he gets back to work soon to erase the memory of it.

Then there's Redacted. In 1989, De Palma made Casualties of War, one of his most sincere films and perhaps the only one to lack any postmodern flourishes. Redacted seeks to rectify this: it swaps Vietnam for Iraq and swaps the classical filmmaking of Casualties for a collage of styles and media. De Palma constructs his film as a hodgepodge of footage sources. The intent is clear: by stylistically and narratively repurposing Casulaties' true story of a rape and massacre being arduously brought to light, Redacted uses its own dramatization of real events to demonstrate that, in a war that can now be documented by anyone with a cell phone, truth has never been further from the public's grasp. If Casualties of War found worth, even moral victory in doing the right thing, Redacted nihilistically sees no point in even trying.

For that very reason, all the incisive ideas percolating through Redacted's slim running time cannot prevent it from being one of the most abysmal, unbearable movies De Palma ever made, ranking among the dregs with Bonfire of the Vanities and Wise Guys. It's a shame, too, for Redacted occasionally flirts with greatness, suggesting a vicious assault on oblivious American mindsets since the "Be Black, Baby" segment of Hi, Mom! But from the first moments, one can tell that Redacted will be a miserable chore, not a galvanizing screed.

The film follows a company of soldiers stationed in Iraq, where they already chafe under the hot desert sun and tense relations with the indigenous population. One soldier, Angel Salazar (Izzy Diaz), decides to film life on the base, believing that his work will get him into film school when he goes home. There's a grim irony to this thought process, the home videos a young Steven Spielberg used to make where he and his friends reenacted war now replaced by a taping of a real one. But his journal reveals the first, and deadliest, flaw of the movie: Salazar, and his comrades, could not be more simplistically written or agonizingly two-dimensional. To a T, they make casually racist comments about Iraqis and show no remorse for their lethal screw-ups. A green soldier ends up killing a woman at a checkpoint when her car speeds through, and not only does he not struggle with it, he brags into Salazar's camera.

Only Salazar and another soldier, Lawyer McCoy (Rob Devaney), ever even hint at a basic humanity, and they are no more nuanced than their rapacious brethren. They are moral simply because the script calls for someone to be at least partially decent, and their protests to increasingly horrific behavior have all the conviction of a bored high-schooler forced to read a play aloud in class and doing so with a flat, get-it-over-with monotone. The squad leads a raid on a local home that they suspect contains intel, where they arrest a man for no reason as a reporter for an Al-Jazeera-like news organization asks the soldiers what they are doing. Later, some of the soldiers decide to return to have their way with a 15-year-old girl they saw in the house, killing her and her family in the process. Salazar is forced to witness it, and a protesting McCoy is thrown out by his comrades at gunpoint.

That's the basic gist of the story, but De Palma tries to dress it up with his use of multiple styles. Unfortunately, the result is an interminable mess. De Palma's asides with a group of French documentarians parody stuffy, emptily moralistic war docs, the camera slowly zooming in and out on soldiers' faces as the orchestral arrangement of "Sarabande" from Barry Lyndon plays. At least, I assume it's a parody; these segments are so tedious that De Palma must be making fun of such films, but his target is unclear. Likewise, we see various YouTube clips of terrorists sneaking bombs under the clueless eyes of the Americans, or of newscasts showing angry Iraqis swearing vengeance for what has happened to them. Everyone knows what the Americans are doing, but no one will listen.

It might be an compelling array of conflicting, yet harmonious, elements were the transitions not so jarring, the morals not so disgustingly black-and-white, and the judgment not so haughty. Casualties of War grounded its characters' sadism in an understanding for their predicament. It vigorously condemned the actions of the soldiers, but it could also at least see how they were driven to the point of feral madness. Redacted feels like an old man's rant about "kids these days," only the kids here murder a family in cold blood and set fire to a teenager after raping her. It just accepts the horror of the soldiers' actions as a foregone conclusion. Salazar blanches at the atrocity, but he also wants to reveal the truth in a way that will make his film project a hit; better to get back home and piece together a dynamite cut than get justice now. And all McCoy can do is feel bad, even up to his last moment on-screen, which openly mocks him.

War is unpleasant, and the Iraq War more unpleasant than most, given its falsified justification and mismanagement. But De Palma's usual talent for immersion in seediness fails him here. He does not capture the repulsion of war; he only makes a repulsive film. As if to ward off the pointlessness of the exercise, De Palma has his characters occasionally spout aesthetic maxims. When Salazar jokingly tells McCoy that his camera doesn't lie, McCoy replies, "That's bullshit because that's all that camera ever does." Later, Salazar more insistently urges, "Just because you watch it doesn't mean you're not a part of it." Naturally, both of these utterances are key positions of De Palma's entire approach and philosophy, but so hear them said aloud here cheapens them. Especially the latter quote; De Palma is a master of implicating his audience, up there with Alfred Hitchcock and Michael Haneke. But this film does not implicate anyone because it is so morally rigid. Casualties of War shows a situation slowly spiraling off its axis until the breaking point isn't visible. These men broke before they even left home. What, then, can we learn of them?

And why is the movie so unsparing? As with the Incident on Hill 192, the real-life Mahmudiyah killings were punished. In fact, they were punished far more severely than the incident that spawned Casualties of War. The soldiers who raped the Vietnamese girl and destroyed her village had their sentences drastically reduced, and in some cases dropped entirely. The three soldiers involved in Mahmudiyah, however, have received multiple life sentences. To end the film on an uncertain note is just bullshit posturing, an offensive recalibration of reality to fit a tidy, repellent premise. The problem with this film is that De Palma, though still a provocateur, cannot now conjure the same anarchist energy of his earliest days. When he inserts an embarrassing YouTube rant by a single-minded teenage liberal, he does not broaden the scope of his critique of contemporary culture. He merely chucks in one more stereotype to be lazily jabbed, nothing more than the wink of a shock comic grown too old.

There are so many good ideas in Redacted. The fat soldier's first raid through the house borders on the Orwellian as he seizes documents he cannot read for evidence so that he can give them to a translator to determine if they are actually evidence. The blood stains left by the dead recall those thick lines of permanent marker blacking out sensitive information, erasing the full detail of the person who was there while still leaving an unmistakable trace of malfeasance. The cross-format collage of video sources presages Film Socialisme in a Derridean attempt to chase truth through the multitude of options now available to us and coming up shorter than ever. But the lapse of De Palma's subtlety results in a film that feels like a repository for every charge ever leveled against him, from misogyny to cheap cynicism to hollow rip-offs (the music lift from Barry Lyndon and a recreation of the scorpion and ants shot from The Wild Bunch add nothing). Many of De Palma's films have vile traits, but they are usually intentionally added, well-illustrated travesties cleverly dismantled by De Palma, who can be in the thick of it and above it all at once. This, however, is the only one of his films I've ever found truly disgusting, and I hope that he gets back to work soon to erase the memory of it.

Saturday, February 25

Brian De Palma: The Black Dahlia

Building off the moral investigation of film noir that characterized his Femme Fatale, Brian De Palma's The Black Dahlia is a grim, stylish examination of the whole genre, not merely one of its most vital foundations. An adaptation of a fictionalization of a real murder committed in Hollywood, The Black Dahlia is ripe for De Palma's approach, but his film is less a deconstruction than a demolition, its elegant, formalist structure nonetheless betraying jagged edges that rip apart film noir. At its face value, the film is perhaps the director's most aesthetically pleasing, with its golden hues and plunging shadows casting Hollywood as its own cinematized fantasy and nightmare. More importantly, however, it is easily De Palma's most profoundly disturbing film, as transgressive in its own way as Body Double, only more formal and emotional. Body Double assaults the senses, but The Black Dahlia hits where it hurts.

Narrated in terse, strained voiceover by Dwight "Bucky" Bleichert (Josh Hartnett), The Black Dahlia feels like a noir from the start, even as it introduces its detectives via their alternate gig, boxers for the force. If Femme Fatale delved into the characteristic female type of noir, The Black Dahlia breaks down the male cop archetypes. We meet Dwight "Bucky" Bleichert (Josh Hartnett) as Mr. Ice and Lee Blanchard (Aaron Eckhart) as "Mr. Fire," their accomplishments as police officers nothing more than mere fodder for hyping this exhibition match for the precinct. It casts the two as leading men not merely of the film but of its diegetic world, headliners revered for their crowd-pleasing qualities. This presentation fundamentally weakens the two men as serious police officers, but De Palma will spend the rest of the movie undermining them even more, digging into the grim, unheroic truths beneath their aesthetically captivating shells.

Blanchard and Bleichert make perfect foils for each other. Blanchard, sporting Eckhart's magnificent chin and Aryan hair, looks like the national perception of the "All-American" and resides in a house so big that even his colleagues must want to investigate his tax returns. Bleichert, smaller and brunette, returns to his cheap apartment to care for his dementia-ridden, German immigrant father. Bleichert takes a dive in their fight in order to put his dad in a home, but his voiceovers suggest that he knew Blanchard had to win anyway. For the good of the department, the son of a Jerry was always going to have to get pummeled by Captain America.

Yet Blanchard proves to be a sport about their rigged match, and the two become close friends. The merciless staging of the boxing scenes—filmed by De Palma in ways that make Raging Bull look tame—fades into an equally exaggerated view of camaraderie between the partners. De Palma even suggests that the two have bonded so thoroughly that they practically share the same woman, Blanchard's girlfriend Kay Lake (Scarlett Johansson). But as quickly as De Palma casts Blanchard and Bleichert as the purest form of the buddy cop cliché, he sets about rending them apart. Muttered half-revelations hint at dark secrets that inform the odd sort of love triangle between Kay and the two officers, and when they get drawn into the investigation of the infamous titular murder case, their collective type crumbles.

The discovery of the "Black Dahlia," Elizabeth Short (Mia Kirshner), occurs in the background of a stakeout Blanchard and Bleichert plan for a serial rapist/murderer, and De Palma thickly lays on the grim irony of this white woman's death instantly taking precedent at the precinct over the tailed violator and killer of black children. Bleichert himself tries to get this across to Blanchard, but his partner swiftly forgets about his initial target to focus on the case of this gruesomely disfigured corpse. Bleichert, who perhaps feels at least some form of kinship with the neglected elements of society as a second-generation immigrant, is more repulsed by the idea of children dying regardless of race. Blanchard, though, wants to find the person responsible for the killing of an attractive white woman. And as clues filter in about her sexual past, his dedication morphs into obsession.

If De Palma's previous film tacitly criticized the Nice Guy™faux-chivalric male, The Black Dahlia fully attacks it. Bleichert gradually pieces together Kay's past out of vague, fearful allusions until he realizes she was a prostitute tortured by her pimp. Blanchard rescued her, but as Kay tells Bleichert, he's never slept with her. Male judgment of female sexuality pervades the film, and Blanchard's visceral reaction to sex illustrates this most clearly. His dedication to the Elizabeth Short case exhibits his need to protect women, but also his revulsion of them. The discovery of seedy "audition tapes" featuring Short only further feed his rage. De Palma sprinkles misogyny throughout—Short's own father practically says she deserved what she got for dressing the way she did—but the treatment of Blanchard bitterly deconstructs the seemingly noble impulse to save or avenge the wronged damsel to its roots, which are no less hateful.

Bleichert, on the other hand, lacks Blanchard's fierceness but makes up for it by feeling all the lust Blanchard denies himself. His friendship with Kay flirts with inappropriateness, with Kay's repressed sexuality eking out around the man, whose own feelings are stirred in her presence. However, Bleichert pulls back when he senses himself growing too close, prioritizing his relationship with Blanchard over the one with her. More intriguing, though, is the romance Bleichert ultimately enters into with Elizabeth Short's doppelganger, a pampered rich girl named Madeline Linscott (Hilary Swank) who likes to slum it in some of the lesbian bars Short used to visit. De Palma has long loved his doubles, but what makes Madeline unique is the relative lack of definition of her "real" self. The Black Dahlia is a wisp of memory, a vague outline of corrupted innocence that represents perhaps the most purified and cynical end to the poor rube who came to Hollywood to follow her dream. Madeline is, of course, the reverse; her family helped build Tinseltown and in turn made boatloads of money. But she, like everyone else in her mad clan, is perverse and exploitative, the sort of person who corrupts the corruptible like Short.

But Bleichert doesn't care. He plays Blanchard's id as much as Madeline (a Vertigo reference, perhaps?) plays Elizabeth's, and the two soon enter into a sexual affair. Madeline adheres more faithfully to the femme fatale type that De Palma so brilliantly subverted with his last film, yet he adds a class twist to her schemes that run counter to the usual motive of greed. Instead of manipulating people for personal gain, she seems to do it just to get some kind of thrill. Cloistered in aristocratic misery with her internally squabbling family, Madeline gets her jollies seducing a woman who looks like her, or twisting this hapless detective around her pinky finger. All of the loathing Blanchard pours onto the image of Short would be better directed at this embodiment of all he hates about her, but it's his partner who ends up sticking it to her, in more ways than one.

In contrast to the men and their projection of women, Short herself is complex and heart-wrenching. This is all the more striking given that the audience only "interacts" with her via old those old tapes of grimy audition reels. Kirshner brings out depths of tragedy to the woman in fragmented bursts, playing Short with just enough cynicism to try to seduce her off-camera mocker but too much innocence to do it with any more conviction than a child aping something she should never have been allowed to see. Adamant in her desire to be a star, Short is nevertheless so timid and fragile that the misogynistic accusations thrown at her memory evaporate. A tragic air pervades the film, but elsewhere it is subdued in cold shock. Whenever Kirshner appears in black-and-white, half-heartedly rousing herself against the horrid casting director (De Palma himself, off-screen), her barely contained despair jumps through the diegetic camera and then through De Palma's lens. Her looks feel like addresses to the audience's decency, and the unbearableness of it drives Blanchard insane.

The Black Dahlia is based on the book by James Ellroy, whose L.A. Confidential is regularly cited as one of the great American films of the last 20 years. That film frames Ellroy's unsparingly critical view of Hollywood with a formal perfection, its layered narrative nonetheless neatly arranged and its direction generally crisp and uncomplicated. De Palma's film is precisely the opposite of all that. It's messy, self-annihilating and convoluted. Yet it is De Palma's movie, not Curtis Hanson's, that visually embodies the tone in which Ellroy's writing casts Hollywood. Vilmos Zgimond's gorgeous cinematography uses golden hues and deep shadow to duplicitous effect, at once highlighting the nostalgic and idealistic glory of show business and its jaundiced, rotting underbelly.

In addition, De Palma understands that Hollywood, like the rest of America, was erected by immigrants and frontiersmen, often moves back past noir into German Expression itself. The stylized L.A. never truly settles into any form of realism, and by the end it's morphed into an outright fever dream of despair and confused longing on behalf of Bleichert, whose flat narration prevents one from easily guessing that the whole movie is his delirious nightmare until the final moments. De Palma regularly checks the great Expressionist film The Man Who Laughs, not only as a recurring image but a key plot point. He even throws in his own tragically yearning and disfigured character, and anyone who knows their De Palma will know instantly that such a character simply must be played by William Finley.

The dizzying, extended climax to The Black Dahlia is at once one of the most controlled freak-outs in De Palma's canon and one of the most unsettling. Bleichert, still reeling from a stunning second act finale, falls fully into madness, and the plot suddenly speeds up to accommodate his plummet. The Expressionist touches turn into full swaths of stylized acting and staging, most memorably the grim fate of Madeline's mother, whose gagging dignity made for such great comedy in an earlier dinner scene but suddenly seems frightful and insane. Other influences beging pouring in as well, from a confrontation with Madeline that makes the Vertigo connection more than plausible to what even appears to be a lift from F for Fake.

But nothing compares to the last scene, the most elegant, Romantic obliteration since De Palma caught up to Carlito's Way's foregone conclusion. Bewildered and enraged, Bleichert returns to Kay for comfort, seeking shelter from what he has seen and uncovered. Kay opens the door in a flash of heavenly white, the whore become the Madonna as she beckons the man inside. But before he can move, Bleichert hears the caw of a crow behind him and turns to see Betty Short's mutilated corpse lying on the lawn, illuminated by Kay's glow, the object of his ecstasy also a reminder of his agony. In that moment, Bleichert finds himself frozen between equally garish reminders of his two biggest failures, to the case, and to his friend and partner. It's worth noting that when Bleichert shakes his head and the ghastly image of Short disappears, so too does Kay's aura. This flash of lucidity breaks up the subjective haze of the film's last 15-20 minutes, yet Bleichert's conscious decision to retreat from the world with Kay may be more unsettling than any of the stylized actions that preceded it.

Earlier I mentioned the stylistic ways that the more graceful Black Dahlia diverged from the full-on porn assault of Body Double, yet if anything, it's the 2006 film that is more merciless. Body Double spits on what Hollywood had become; as Bleichert enters the house with Kay and shuts himself off from the horror around him, The Black Dahlia makes clear that Hollywood was always the most loathsome, horrifying place in the world.

Narrated in terse, strained voiceover by Dwight "Bucky" Bleichert (Josh Hartnett), The Black Dahlia feels like a noir from the start, even as it introduces its detectives via their alternate gig, boxers for the force. If Femme Fatale delved into the characteristic female type of noir, The Black Dahlia breaks down the male cop archetypes. We meet Dwight "Bucky" Bleichert (Josh Hartnett) as Mr. Ice and Lee Blanchard (Aaron Eckhart) as "Mr. Fire," their accomplishments as police officers nothing more than mere fodder for hyping this exhibition match for the precinct. It casts the two as leading men not merely of the film but of its diegetic world, headliners revered for their crowd-pleasing qualities. This presentation fundamentally weakens the two men as serious police officers, but De Palma will spend the rest of the movie undermining them even more, digging into the grim, unheroic truths beneath their aesthetically captivating shells.

Blanchard and Bleichert make perfect foils for each other. Blanchard, sporting Eckhart's magnificent chin and Aryan hair, looks like the national perception of the "All-American" and resides in a house so big that even his colleagues must want to investigate his tax returns. Bleichert, smaller and brunette, returns to his cheap apartment to care for his dementia-ridden, German immigrant father. Bleichert takes a dive in their fight in order to put his dad in a home, but his voiceovers suggest that he knew Blanchard had to win anyway. For the good of the department, the son of a Jerry was always going to have to get pummeled by Captain America.

Yet Blanchard proves to be a sport about their rigged match, and the two become close friends. The merciless staging of the boxing scenes—filmed by De Palma in ways that make Raging Bull look tame—fades into an equally exaggerated view of camaraderie between the partners. De Palma even suggests that the two have bonded so thoroughly that they practically share the same woman, Blanchard's girlfriend Kay Lake (Scarlett Johansson). But as quickly as De Palma casts Blanchard and Bleichert as the purest form of the buddy cop cliché, he sets about rending them apart. Muttered half-revelations hint at dark secrets that inform the odd sort of love triangle between Kay and the two officers, and when they get drawn into the investigation of the infamous titular murder case, their collective type crumbles.

The discovery of the "Black Dahlia," Elizabeth Short (Mia Kirshner), occurs in the background of a stakeout Blanchard and Bleichert plan for a serial rapist/murderer, and De Palma thickly lays on the grim irony of this white woman's death instantly taking precedent at the precinct over the tailed violator and killer of black children. Bleichert himself tries to get this across to Blanchard, but his partner swiftly forgets about his initial target to focus on the case of this gruesomely disfigured corpse. Bleichert, who perhaps feels at least some form of kinship with the neglected elements of society as a second-generation immigrant, is more repulsed by the idea of children dying regardless of race. Blanchard, though, wants to find the person responsible for the killing of an attractive white woman. And as clues filter in about her sexual past, his dedication morphs into obsession.

If De Palma's previous film tacitly criticized the Nice Guy™faux-chivalric male, The Black Dahlia fully attacks it. Bleichert gradually pieces together Kay's past out of vague, fearful allusions until he realizes she was a prostitute tortured by her pimp. Blanchard rescued her, but as Kay tells Bleichert, he's never slept with her. Male judgment of female sexuality pervades the film, and Blanchard's visceral reaction to sex illustrates this most clearly. His dedication to the Elizabeth Short case exhibits his need to protect women, but also his revulsion of them. The discovery of seedy "audition tapes" featuring Short only further feed his rage. De Palma sprinkles misogyny throughout—Short's own father practically says she deserved what she got for dressing the way she did—but the treatment of Blanchard bitterly deconstructs the seemingly noble impulse to save or avenge the wronged damsel to its roots, which are no less hateful.

Bleichert, on the other hand, lacks Blanchard's fierceness but makes up for it by feeling all the lust Blanchard denies himself. His friendship with Kay flirts with inappropriateness, with Kay's repressed sexuality eking out around the man, whose own feelings are stirred in her presence. However, Bleichert pulls back when he senses himself growing too close, prioritizing his relationship with Blanchard over the one with her. More intriguing, though, is the romance Bleichert ultimately enters into with Elizabeth Short's doppelganger, a pampered rich girl named Madeline Linscott (Hilary Swank) who likes to slum it in some of the lesbian bars Short used to visit. De Palma has long loved his doubles, but what makes Madeline unique is the relative lack of definition of her "real" self. The Black Dahlia is a wisp of memory, a vague outline of corrupted innocence that represents perhaps the most purified and cynical end to the poor rube who came to Hollywood to follow her dream. Madeline is, of course, the reverse; her family helped build Tinseltown and in turn made boatloads of money. But she, like everyone else in her mad clan, is perverse and exploitative, the sort of person who corrupts the corruptible like Short.

But Bleichert doesn't care. He plays Blanchard's id as much as Madeline (a Vertigo reference, perhaps?) plays Elizabeth's, and the two soon enter into a sexual affair. Madeline adheres more faithfully to the femme fatale type that De Palma so brilliantly subverted with his last film, yet he adds a class twist to her schemes that run counter to the usual motive of greed. Instead of manipulating people for personal gain, she seems to do it just to get some kind of thrill. Cloistered in aristocratic misery with her internally squabbling family, Madeline gets her jollies seducing a woman who looks like her, or twisting this hapless detective around her pinky finger. All of the loathing Blanchard pours onto the image of Short would be better directed at this embodiment of all he hates about her, but it's his partner who ends up sticking it to her, in more ways than one.

In contrast to the men and their projection of women, Short herself is complex and heart-wrenching. This is all the more striking given that the audience only "interacts" with her via old those old tapes of grimy audition reels. Kirshner brings out depths of tragedy to the woman in fragmented bursts, playing Short with just enough cynicism to try to seduce her off-camera mocker but too much innocence to do it with any more conviction than a child aping something she should never have been allowed to see. Adamant in her desire to be a star, Short is nevertheless so timid and fragile that the misogynistic accusations thrown at her memory evaporate. A tragic air pervades the film, but elsewhere it is subdued in cold shock. Whenever Kirshner appears in black-and-white, half-heartedly rousing herself against the horrid casting director (De Palma himself, off-screen), her barely contained despair jumps through the diegetic camera and then through De Palma's lens. Her looks feel like addresses to the audience's decency, and the unbearableness of it drives Blanchard insane.

The Black Dahlia is based on the book by James Ellroy, whose L.A. Confidential is regularly cited as one of the great American films of the last 20 years. That film frames Ellroy's unsparingly critical view of Hollywood with a formal perfection, its layered narrative nonetheless neatly arranged and its direction generally crisp and uncomplicated. De Palma's film is precisely the opposite of all that. It's messy, self-annihilating and convoluted. Yet it is De Palma's movie, not Curtis Hanson's, that visually embodies the tone in which Ellroy's writing casts Hollywood. Vilmos Zgimond's gorgeous cinematography uses golden hues and deep shadow to duplicitous effect, at once highlighting the nostalgic and idealistic glory of show business and its jaundiced, rotting underbelly.

In addition, De Palma understands that Hollywood, like the rest of America, was erected by immigrants and frontiersmen, often moves back past noir into German Expression itself. The stylized L.A. never truly settles into any form of realism, and by the end it's morphed into an outright fever dream of despair and confused longing on behalf of Bleichert, whose flat narration prevents one from easily guessing that the whole movie is his delirious nightmare until the final moments. De Palma regularly checks the great Expressionist film The Man Who Laughs, not only as a recurring image but a key plot point. He even throws in his own tragically yearning and disfigured character, and anyone who knows their De Palma will know instantly that such a character simply must be played by William Finley.

The dizzying, extended climax to The Black Dahlia is at once one of the most controlled freak-outs in De Palma's canon and one of the most unsettling. Bleichert, still reeling from a stunning second act finale, falls fully into madness, and the plot suddenly speeds up to accommodate his plummet. The Expressionist touches turn into full swaths of stylized acting and staging, most memorably the grim fate of Madeline's mother, whose gagging dignity made for such great comedy in an earlier dinner scene but suddenly seems frightful and insane. Other influences beging pouring in as well, from a confrontation with Madeline that makes the Vertigo connection more than plausible to what even appears to be a lift from F for Fake.

But nothing compares to the last scene, the most elegant, Romantic obliteration since De Palma caught up to Carlito's Way's foregone conclusion. Bewildered and enraged, Bleichert returns to Kay for comfort, seeking shelter from what he has seen and uncovered. Kay opens the door in a flash of heavenly white, the whore become the Madonna as she beckons the man inside. But before he can move, Bleichert hears the caw of a crow behind him and turns to see Betty Short's mutilated corpse lying on the lawn, illuminated by Kay's glow, the object of his ecstasy also a reminder of his agony. In that moment, Bleichert finds himself frozen between equally garish reminders of his two biggest failures, to the case, and to his friend and partner. It's worth noting that when Bleichert shakes his head and the ghastly image of Short disappears, so too does Kay's aura. This flash of lucidity breaks up the subjective haze of the film's last 15-20 minutes, yet Bleichert's conscious decision to retreat from the world with Kay may be more unsettling than any of the stylized actions that preceded it.

Earlier I mentioned the stylistic ways that the more graceful Black Dahlia diverged from the full-on porn assault of Body Double, yet if anything, it's the 2006 film that is more merciless. Body Double spits on what Hollywood had become; as Bleichert enters the house with Kay and shuts himself off from the horror around him, The Black Dahlia makes clear that Hollywood was always the most loathsome, horrifying place in the world.

Posted by

wa21955

Labels:

2006,

Aaron Eckhart,

Brian De Palma,

Hilary Swank,

Josh Hartnett,

Scarlett Johansson,

William Finley

Thursday, February 2

Brian De Palma: Femme Fatale

After the reception of Mission to Mars took some of the wind out of De Palma's sails, Femme Fatale represented a more modestly scaled return to the director's well of head-trip thrillers. But fresh off the (perceived) defeat of his least ironic bid for a winsomely broad-audience movie, De Palma came up with what may be his densest, most complex work. Taking a page from the Body Double-esque travesty he trotted out every few years since that 1984 masterpiece to remind everyone who's boss, Femme Fatale is defiantly nonsensical and deliberately self-annihilating. Like all the rest of the pure style exercises the director's made since Body Double, Femme Fatale doesn't reach the same heights of anarchic frenzy, but De Palma makes a key choice to move away from mere stylistic flourishes to try to make his flashy neo-noir say something.

Femme Fatale follows Laure Ash (Rebecca Romijn), who embodies the titular concept to such a pure degree that the first we see of her is a reflection of her face in a television as she watches one of the quintessential femme fatale movies, Double Indemnity. By the end of the extended and wild opening, she's already seduced a woman and double-crossed her gang of dangerous criminals, and she'll only prove more manipulative from there. But even as De Palma brings out the distilled essence of that character type's destructive properties, he also contextualizes it with equally outsized depictions of the misogyny that surrounds such a character. The head of the criminals she works with at the start (Eriq Ebouaney) slaps her before their mission even begins, and I don't think he ever once so much as refers to Laure throughout the film without using the term "bitch." De Palma, who fielded accusations of misogyny throughout the '80s, makes Black Tie's vulgar harassments so unpleasant that he makes clear his disdain for the masculine brutality that drives so many of his characters. De Palma the offense-baiting provocateur this is not.

But I'm already afraid I've given off the impression that the film isn't a riot, which it is from the start. Echoing the vicious feed-hand-biting of Body Double, the opening sequence, a diamond heist set, of all places, at the Cannes Film Festival, is a deliciously wry slash at the movie industry. Even the most prestigious film gala in the world is not immune to the ouroboric culture of tabloids and calculated buzz: the diamonds targeted by the thieves are worn in an absurd metal contrapion that barely warps around a starlet's supple frame in such a way as to make Princess Leia's metal bikini look like a chador in comparison. Vaguely resembling the director's data theft sequence in Mission: Impossible, this setpiece is outlandishly directed with the usual focus on surveillance and divided frames, but none of the tricks is as amusing as that ridiculous diamond getup. It's telling that the film being shown at the festival is utterly incidental to everything happening around it, and that would be as true if there were no heist to focus the audience. For everyone at the ceremony, all eyes are on Veronica and her only occasionally covered nipples. So, while the rest of the film may not go after the industry with the same rabid mania as Body Double, it nevertheless expands that movie's range of attack to slam the foreign market that has been equally corrupted by promotional interests and empty succès de scandale.

After Laure double-crosses her accomplices, she hides out in Belleville until she can get a fake passport to escape the country. She cannot stay hidden for long, though, and De Palma slowly introduces a wrinkle into the proceedings with a split-screen segment that juxtaposes two very different kinds of surveillance of a wigged Laure. On the left, we see Nicolas Bardo (Antonio Banderas), a sometimes-paparazzo who just seems to be interested by seeing the disguised Laure meeting with a contact wearing fashionable camouflage. On the right are the betrayed criminals who've tracked her down. The two contrasting shots reveal different angles, observations and emotional tones. Though Nicolas peers down from above in a more threatening position, his POV is playful, tracking that which catches his eye. It is the more ground-level view of Black Tie's second-in-command that exudes the feeling of being watched, of being plotted.

Laure retreats into the church nearby, but De Palma maintains the divided screen showcasing two watchers. What changes is who's doing the watching. The right half of the screen continues to show the perspective of a jilted accomplice, albeit a different one. But now the left half belongs to an old French couple who look back at Laure with wide-eyed recognition. Between Nicolas' mysterious curiosity and this pair's even stranger response to Laure, De Palma generates confused, ambiguous moods that only become more disorienting and suggestive when placed against the more simplistic feelings of vengeance and lingering hatred of the criminals. As my blogging buddy Ryan Kelly put it in his own fantastic review of the film, "It's all a matter of perspective."

Ryan rightly pinpoints the film as a moral examination of noir, and he references the hazy, equally nostalgic-yet-critical Mulholland Dr. in De Palma's staging of an extended dream sequence and the way that it dramatically alters the thematic focus of the film. Here, the central divide between dream and reality (or dream and other dream) is the suicide of Laure's doppelganger, the troubled daughter of a French couple who take Laure in after mistaking her for their child. By placing the film on such a dramatic crux, De Palma also invites comparisons to Run Lola Run, an action film in which the protagonist is given do-overs save herself and others. In a sense, Femme Fatale is a more emotive, insightful take on Raising Cain, with its constantly upheaved nightmares deliberately shattering any connection to the narrative. A similar postmodern slyness is at work here, but the abandon of Cain and Body Double is replaced by a nuanced take on a common genre element.

De Palma ingeniously finds a way to make Laure adhere to all the manipulative and sexual traits of a femme fatale while undermining the type's context. The aforementioned misogyny of Black Tie's gang does not necessarily justify Laure's behavior, but it does at least provide a contrast for the usual condemnation of the duplicitous jezebel as an agent of feminine evil. But aggressive sexism is not the only male target of De Palma's lens. Later in the film, when Nicolas stumbles into an insane situation in which he sees himself as Laure's deliverer, she gets one over on him too. De Palma does not spare the condescending, faux-chivalrous knight in shining armor from mockery, undercutting the traditionally acceptable position of a man placing a woman in a position of weakness for the purpose of "saving" her. Ryan links this situation, in which "the woman is the one in charge and the man is powerless," to De Palma's larger canon, but this is powerful even for De Palma; I can't think of an example where he emasculated his male character so incisively.

Romijn handles the role magnificently, suddenly leaping into a double life as the dearly departed Lily and subtly bringing her old self back to light when Nicolas comes back into her life as a different kind of male obstacle. Her toothy smile looks almost bestial at times, sadistic glee crossing her face when she succeeds in getting one over on another man. Her handling of Brado, incessantly revealing her superior planning just when he thinks he's won. But Banderas himself is multifaceted (he even gets to play a double life of his own in a hilarious scene), and Nicholas is cleverer than he seems. If he still finds himself constantly thwarted by Laure/Lily's wiles, the photographer nevertheless is the only man resilient enough to consistently return for more. If De Palma does not let Nicolas off the hook for his presumptuousness, nor does he seek to destroy the man with the same zeal as Black Tie's band of vicious misogynists. There is a willingness to forgive and start anew wholly absent from the director's early, more freeform days.

That new mindset informs one of the most beautiful second chances in cinema, a narrative mulligan that uses the reflexive, even absurdist nature of the story's structure to stage a purely moral reset. I don't know that I agree with Ryan regarding his thoughts on the film's treatment of "fate." I would say that the recurrence of images and events owes more to De Palma's delight in mirror imagery, though the film's final shot certainly supports the idea that, while we can choose our own paths, every possible outcome is at least somewhat guided. But the choices made by Laure after the third act upheaval seem to me more a rebellion against that fate, Laure confronting not only the pre-ordained order of events but her own existential trap. The final shot speaks more to the dream logic of the film, but even if this is all a strictly ordered exercise in style, its redemptive final moments place it among the most moving and intelligent of De Palma's films, the perfect marriage of his deconstructive style with the flecks of deep Romantic maturity that informs his best late work.

Femme Fatale follows Laure Ash (Rebecca Romijn), who embodies the titular concept to such a pure degree that the first we see of her is a reflection of her face in a television as she watches one of the quintessential femme fatale movies, Double Indemnity. By the end of the extended and wild opening, she's already seduced a woman and double-crossed her gang of dangerous criminals, and she'll only prove more manipulative from there. But even as De Palma brings out the distilled essence of that character type's destructive properties, he also contextualizes it with equally outsized depictions of the misogyny that surrounds such a character. The head of the criminals she works with at the start (Eriq Ebouaney) slaps her before their mission even begins, and I don't think he ever once so much as refers to Laure throughout the film without using the term "bitch." De Palma, who fielded accusations of misogyny throughout the '80s, makes Black Tie's vulgar harassments so unpleasant that he makes clear his disdain for the masculine brutality that drives so many of his characters. De Palma the offense-baiting provocateur this is not.

But I'm already afraid I've given off the impression that the film isn't a riot, which it is from the start. Echoing the vicious feed-hand-biting of Body Double, the opening sequence, a diamond heist set, of all places, at the Cannes Film Festival, is a deliciously wry slash at the movie industry. Even the most prestigious film gala in the world is not immune to the ouroboric culture of tabloids and calculated buzz: the diamonds targeted by the thieves are worn in an absurd metal contrapion that barely warps around a starlet's supple frame in such a way as to make Princess Leia's metal bikini look like a chador in comparison. Vaguely resembling the director's data theft sequence in Mission: Impossible, this setpiece is outlandishly directed with the usual focus on surveillance and divided frames, but none of the tricks is as amusing as that ridiculous diamond getup. It's telling that the film being shown at the festival is utterly incidental to everything happening around it, and that would be as true if there were no heist to focus the audience. For everyone at the ceremony, all eyes are on Veronica and her only occasionally covered nipples. So, while the rest of the film may not go after the industry with the same rabid mania as Body Double, it nevertheless expands that movie's range of attack to slam the foreign market that has been equally corrupted by promotional interests and empty succès de scandale.

After Laure double-crosses her accomplices, she hides out in Belleville until she can get a fake passport to escape the country. She cannot stay hidden for long, though, and De Palma slowly introduces a wrinkle into the proceedings with a split-screen segment that juxtaposes two very different kinds of surveillance of a wigged Laure. On the left, we see Nicolas Bardo (Antonio Banderas), a sometimes-paparazzo who just seems to be interested by seeing the disguised Laure meeting with a contact wearing fashionable camouflage. On the right are the betrayed criminals who've tracked her down. The two contrasting shots reveal different angles, observations and emotional tones. Though Nicolas peers down from above in a more threatening position, his POV is playful, tracking that which catches his eye. It is the more ground-level view of Black Tie's second-in-command that exudes the feeling of being watched, of being plotted.

Laure retreats into the church nearby, but De Palma maintains the divided screen showcasing two watchers. What changes is who's doing the watching. The right half of the screen continues to show the perspective of a jilted accomplice, albeit a different one. But now the left half belongs to an old French couple who look back at Laure with wide-eyed recognition. Between Nicolas' mysterious curiosity and this pair's even stranger response to Laure, De Palma generates confused, ambiguous moods that only become more disorienting and suggestive when placed against the more simplistic feelings of vengeance and lingering hatred of the criminals. As my blogging buddy Ryan Kelly put it in his own fantastic review of the film, "It's all a matter of perspective."

Ryan rightly pinpoints the film as a moral examination of noir, and he references the hazy, equally nostalgic-yet-critical Mulholland Dr. in De Palma's staging of an extended dream sequence and the way that it dramatically alters the thematic focus of the film. Here, the central divide between dream and reality (or dream and other dream) is the suicide of Laure's doppelganger, the troubled daughter of a French couple who take Laure in after mistaking her for their child. By placing the film on such a dramatic crux, De Palma also invites comparisons to Run Lola Run, an action film in which the protagonist is given do-overs save herself and others. In a sense, Femme Fatale is a more emotive, insightful take on Raising Cain, with its constantly upheaved nightmares deliberately shattering any connection to the narrative. A similar postmodern slyness is at work here, but the abandon of Cain and Body Double is replaced by a nuanced take on a common genre element.

De Palma ingeniously finds a way to make Laure adhere to all the manipulative and sexual traits of a femme fatale while undermining the type's context. The aforementioned misogyny of Black Tie's gang does not necessarily justify Laure's behavior, but it does at least provide a contrast for the usual condemnation of the duplicitous jezebel as an agent of feminine evil. But aggressive sexism is not the only male target of De Palma's lens. Later in the film, when Nicolas stumbles into an insane situation in which he sees himself as Laure's deliverer, she gets one over on him too. De Palma does not spare the condescending, faux-chivalrous knight in shining armor from mockery, undercutting the traditionally acceptable position of a man placing a woman in a position of weakness for the purpose of "saving" her. Ryan links this situation, in which "the woman is the one in charge and the man is powerless," to De Palma's larger canon, but this is powerful even for De Palma; I can't think of an example where he emasculated his male character so incisively.

Romijn handles the role magnificently, suddenly leaping into a double life as the dearly departed Lily and subtly bringing her old self back to light when Nicolas comes back into her life as a different kind of male obstacle. Her toothy smile looks almost bestial at times, sadistic glee crossing her face when she succeeds in getting one over on another man. Her handling of Brado, incessantly revealing her superior planning just when he thinks he's won. But Banderas himself is multifaceted (he even gets to play a double life of his own in a hilarious scene), and Nicholas is cleverer than he seems. If he still finds himself constantly thwarted by Laure/Lily's wiles, the photographer nevertheless is the only man resilient enough to consistently return for more. If De Palma does not let Nicolas off the hook for his presumptuousness, nor does he seek to destroy the man with the same zeal as Black Tie's band of vicious misogynists. There is a willingness to forgive and start anew wholly absent from the director's early, more freeform days.

That new mindset informs one of the most beautiful second chances in cinema, a narrative mulligan that uses the reflexive, even absurdist nature of the story's structure to stage a purely moral reset. I don't know that I agree with Ryan regarding his thoughts on the film's treatment of "fate." I would say that the recurrence of images and events owes more to De Palma's delight in mirror imagery, though the film's final shot certainly supports the idea that, while we can choose our own paths, every possible outcome is at least somewhat guided. But the choices made by Laure after the third act upheaval seem to me more a rebellion against that fate, Laure confronting not only the pre-ordained order of events but her own existential trap. The final shot speaks more to the dream logic of the film, but even if this is all a strictly ordered exercise in style, its redemptive final moments place it among the most moving and intelligent of De Palma's films, the perfect marriage of his deconstructive style with the flecks of deep Romantic maturity that informs his best late work.

Wednesday, October 12

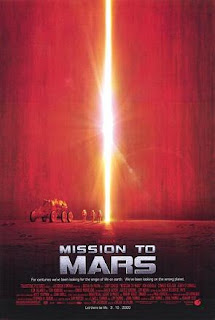

Brian De Palma: Mission to Mars

Brian De Palma's Mission to Mars is the film you'd least expect from the maker of gory, cynical deconstruction who delighted in adhering to genre tropes as much as he did tearing them apart. A PG-rated space adventure released by Disney, Mission to Mars looks on its face like the ultimate sellout move, an embrace of everything De Palma hated now that he could be trusted to make a profit off his work. Certainly critics and audiences found it easy to go with their gut; the film eked out a box office so thinly above the budget it likely falls within the margin of error, and it received scathing reviews from professionals and amateurs alike.

But I see a remarkable film, one that puts all of De Palma's generic immersion and aesthetic strength to use at the opposite end of the emotional spectrum. Here is a film so unabashedly optimistic that De Palma can open on a barbecue with red, white, and blue colors used without a drop of irony, no mean feat for man who loves his American flags huge and imperialistic. And even if one wants to play the usual simplistic game of "Who is De Palma ripping off today?" the closest you'll get is Star Wars by way of 2001. Considering that those two films stand at polar ends to each other, suggesting De Palma is just playing the plagiarist holds even less water than it always has.

That barbecue is a private party on the eve of the titular mission, as American and Russian astronauts celebrate with their families and joke with their colleagues. De Palma establishes the basic character relations through pure exposition, but there's a giddiness on the faces of Tim Robbins, Don Cheadle, Connie Nielsen and the rest that gives the stiff lines a jubilant quality. Even when Jim McConnell (Gary Sinise), the former pilot of the mission taken off assignment when his wife died, arrives, the somber tone still carries flecks of idealism and camaraderie. Cheadle's earnest condolences and reassurances cannot fully overcome how staid the dialogue is, but the look of unendurable pain on Sinise's face, an agony that simmers below his sunken eyes even—especially—when he's smiling ensures that even this trudging moment passes quickly.

But soon the action takes off, De Palma cutting to the first ship's arrival on Mars and their study of the terrain for possible colonization. Orange tinting turns the rocky landscape into a convincing duplicate of Mars, and De Palma uses his widescreen to communicate a sense of loneliness and building unease in these scenes. He also sets up the first of many tricks of perspective, pulling back from the shot of an automated rover on the surface to see its larger, human-carrying counterpart drive past and readjust the scale. Later, in space, a camera swirls outward from four astronauts floating above a flattened atmosphere to likewise reveal the true vastness of the scenario.

Yet these dwarfing visual corrections of perspective belie the intimate nature of the film itself, especially after a mysterious event destroys most of the first crew sent to Mars and prompts the other cluster of characters to fly to Luke Graham's (Cheadle) rescue. De Palma slyly cuts away from Mars just as it starts to resemble a De Palma film, with man's arrogant quest to conquer cut brutally short by a mysterious, unexplained force. By realigning with the second crew, who insist that Jim flies them despite washing out of the program, De Palma moves away from suspense and potential commentary to focus on the struggles and hopes of the team that wants to save Graham but also has six months of travel to kill.

To fill the time, De Palma stages the most joyous, effervescent shots of his career. His camera floats gracefully through space, exuberantly capturing feelings of zero gravity and also communicating an ebullient whimsy wholly absent of the director's usual sense of irony. Giddy to the point of shamelessness, these scenes recast the clinical tone of Kubrick's movement through advanced space stations as pure ecstasy. For Kubrick, the scientifically plausible technology he posited signified man's complete surrender to technology, placing man in an environment where he would literally die without his inventions helping him. But for the Romantic side of De Palma, the ability to explore space gives us the infinity to explore and the ability to leave behind troubles, or at least some of them.

In the film's finest scene, Woody (Robbins), who earlier protested the idea of dance lessons with Terri (Nielsen), puts on Van Halen's "Dance the Night Away" and twirls in zero-gravity with his wife. It's such a happy moment that everyone on-board forgets the mission and watches the two go. De Palma revels in the romance, but he also adds a tinge of sadness when Jim arrives. Sinise plays his part beautifully here, looking on with a smile that does not fade but slowly cools as he thinks of his own wife and how it so easily could have been he and Maggie dancing. It's a quiet, heartbreaking cutaway that displays De Palma's pained humanism stripped of the usual sarcasm or at least doom. That the Mars mission pairs husband and wife in the first place is itself revealing of the director's emotional approach here: in this idealized future, even scientists recognize the need for human comfort and warmth in space and want their mission leaders to be emotionally level. They just recognize that humans are emotionally level when they are happy, not clinically neutral.

All of this is not to say that Mission to Mars contains none of De Palma's darker impulses. But even they are timed to be affecting, not sinister. Consider the scene of Graham's team exploring the aberration in a Martian mountain intercut with the broadcast he and the crew recorded earlier to send back to the space station over Earth. That transmission reaches and plays for the astronauts there just as Graham and co. reach the site, and the cheeriness of the transmission (in which the crew on Mars joke and sing "Happy Birthday" to Jim) conflicts with the mounting suspense of the electronic warbling and gathering wind on Mars. The crosscutting only exacerbates the tension by making the thought of anything happening to these characters (who are all so thinly defined you know few, if any, will survive) unpleasant instead of just expected.

There's also the devastating sequence of the four members of the second mission crew forced to abandon their craft after micrometeorites lead to an engine explosion. As Woody aims for a refueling module, he secures a tether but carries too much momentum to stop, flying outside the range of his friends. Unwilling to watch her husband die, Terri cuts her own tether in a doomed attempt to rescue him, leading Woody to take drastic measures to prevent her from killing herself. His act of self-sacrifice is poignant and poetic, using tense setups—Woody propelling himself too fast, the line on the tether gun reaching its end just before it can reach him—to reach a sorrowful conclusion.

On Mars, the remaining crew reunites with a half-mad Graham, and as they wonder what it is about Mars' atmosphere that might have caused this, Jim points out that he watched his friends die and spent six months as the only man on a planet. Or is he? The storm that destroyed Graham's mission was clearly controlled, and one can only expect aliens to show up at some point. What makes Mission to Mars remarkable is how it (literally) relates those aliens to us. An earlier scene establishes a joke by having Phil (Jerry O'Connell) arrange M&Ms in zero gravity to form a DNA double-helix of what he calls his "ideal woman." Jim reaches out and nabs a few candies, asking Phil what the strand is now. "A frog?" Phil guesses after briefly studying the altered base pairs.

Amusing at that scene is, it also establishes the key theme of De Palma's film, that all life is linked to the same fundamental building blocks, with only the tiniest variations separating vastly different species. The Martians only take this idea to its endpoint, providing an explanation for life on Earth that not only connects all creatures through the huge chunks of DNA they share but does the same for life in the great beyond. For a Disney film that works primarily as an optimistic space adventure, Mission to Mars strikingly reminded me of Terrence Malick's recent The Tree of Life, another film that used a universal canvas and the scientific conclusions of evolution to posit a spiritual connection linking all life.

This is a far cry from De Palma's usual view of humanity, where even his most loving portrayals show characters who are isolated and cut off from the world. The closest he comes to acknowledging his usual forays into underworlds and monsters is a jokey retort from Phil when Terri waxes rhapsodic on the three percent of DNA that makes humanity its own species, the three percent that gave the world Einstein and Mozart. "And Jack the Ripper," chimes Phil. Nevertheless, in Mission to Mars, we are all one, and when Jim decides to leave his empty life behind to seek meaning even deeper into the cosmos, De Palma promises to make him see just how vast the universal web of life is. It may not be De Palma's best film, but Mission to Mars is the most rapturous and hopeful of his stylistic exercises, and one of the finest displays of the love he has under all his cynicism.

But I see a remarkable film, one that puts all of De Palma's generic immersion and aesthetic strength to use at the opposite end of the emotional spectrum. Here is a film so unabashedly optimistic that De Palma can open on a barbecue with red, white, and blue colors used without a drop of irony, no mean feat for man who loves his American flags huge and imperialistic. And even if one wants to play the usual simplistic game of "Who is De Palma ripping off today?" the closest you'll get is Star Wars by way of 2001. Considering that those two films stand at polar ends to each other, suggesting De Palma is just playing the plagiarist holds even less water than it always has.

That barbecue is a private party on the eve of the titular mission, as American and Russian astronauts celebrate with their families and joke with their colleagues. De Palma establishes the basic character relations through pure exposition, but there's a giddiness on the faces of Tim Robbins, Don Cheadle, Connie Nielsen and the rest that gives the stiff lines a jubilant quality. Even when Jim McConnell (Gary Sinise), the former pilot of the mission taken off assignment when his wife died, arrives, the somber tone still carries flecks of idealism and camaraderie. Cheadle's earnest condolences and reassurances cannot fully overcome how staid the dialogue is, but the look of unendurable pain on Sinise's face, an agony that simmers below his sunken eyes even—especially—when he's smiling ensures that even this trudging moment passes quickly.

But soon the action takes off, De Palma cutting to the first ship's arrival on Mars and their study of the terrain for possible colonization. Orange tinting turns the rocky landscape into a convincing duplicate of Mars, and De Palma uses his widescreen to communicate a sense of loneliness and building unease in these scenes. He also sets up the first of many tricks of perspective, pulling back from the shot of an automated rover on the surface to see its larger, human-carrying counterpart drive past and readjust the scale. Later, in space, a camera swirls outward from four astronauts floating above a flattened atmosphere to likewise reveal the true vastness of the scenario.

Yet these dwarfing visual corrections of perspective belie the intimate nature of the film itself, especially after a mysterious event destroys most of the first crew sent to Mars and prompts the other cluster of characters to fly to Luke Graham's (Cheadle) rescue. De Palma slyly cuts away from Mars just as it starts to resemble a De Palma film, with man's arrogant quest to conquer cut brutally short by a mysterious, unexplained force. By realigning with the second crew, who insist that Jim flies them despite washing out of the program, De Palma moves away from suspense and potential commentary to focus on the struggles and hopes of the team that wants to save Graham but also has six months of travel to kill.

To fill the time, De Palma stages the most joyous, effervescent shots of his career. His camera floats gracefully through space, exuberantly capturing feelings of zero gravity and also communicating an ebullient whimsy wholly absent of the director's usual sense of irony. Giddy to the point of shamelessness, these scenes recast the clinical tone of Kubrick's movement through advanced space stations as pure ecstasy. For Kubrick, the scientifically plausible technology he posited signified man's complete surrender to technology, placing man in an environment where he would literally die without his inventions helping him. But for the Romantic side of De Palma, the ability to explore space gives us the infinity to explore and the ability to leave behind troubles, or at least some of them.

In the film's finest scene, Woody (Robbins), who earlier protested the idea of dance lessons with Terri (Nielsen), puts on Van Halen's "Dance the Night Away" and twirls in zero-gravity with his wife. It's such a happy moment that everyone on-board forgets the mission and watches the two go. De Palma revels in the romance, but he also adds a tinge of sadness when Jim arrives. Sinise plays his part beautifully here, looking on with a smile that does not fade but slowly cools as he thinks of his own wife and how it so easily could have been he and Maggie dancing. It's a quiet, heartbreaking cutaway that displays De Palma's pained humanism stripped of the usual sarcasm or at least doom. That the Mars mission pairs husband and wife in the first place is itself revealing of the director's emotional approach here: in this idealized future, even scientists recognize the need for human comfort and warmth in space and want their mission leaders to be emotionally level. They just recognize that humans are emotionally level when they are happy, not clinically neutral.

All of this is not to say that Mission to Mars contains none of De Palma's darker impulses. But even they are timed to be affecting, not sinister. Consider the scene of Graham's team exploring the aberration in a Martian mountain intercut with the broadcast he and the crew recorded earlier to send back to the space station over Earth. That transmission reaches and plays for the astronauts there just as Graham and co. reach the site, and the cheeriness of the transmission (in which the crew on Mars joke and sing "Happy Birthday" to Jim) conflicts with the mounting suspense of the electronic warbling and gathering wind on Mars. The crosscutting only exacerbates the tension by making the thought of anything happening to these characters (who are all so thinly defined you know few, if any, will survive) unpleasant instead of just expected.

There's also the devastating sequence of the four members of the second mission crew forced to abandon their craft after micrometeorites lead to an engine explosion. As Woody aims for a refueling module, he secures a tether but carries too much momentum to stop, flying outside the range of his friends. Unwilling to watch her husband die, Terri cuts her own tether in a doomed attempt to rescue him, leading Woody to take drastic measures to prevent her from killing herself. His act of self-sacrifice is poignant and poetic, using tense setups—Woody propelling himself too fast, the line on the tether gun reaching its end just before it can reach him—to reach a sorrowful conclusion.

On Mars, the remaining crew reunites with a half-mad Graham, and as they wonder what it is about Mars' atmosphere that might have caused this, Jim points out that he watched his friends die and spent six months as the only man on a planet. Or is he? The storm that destroyed Graham's mission was clearly controlled, and one can only expect aliens to show up at some point. What makes Mission to Mars remarkable is how it (literally) relates those aliens to us. An earlier scene establishes a joke by having Phil (Jerry O'Connell) arrange M&Ms in zero gravity to form a DNA double-helix of what he calls his "ideal woman." Jim reaches out and nabs a few candies, asking Phil what the strand is now. "A frog?" Phil guesses after briefly studying the altered base pairs.

Amusing at that scene is, it also establishes the key theme of De Palma's film, that all life is linked to the same fundamental building blocks, with only the tiniest variations separating vastly different species. The Martians only take this idea to its endpoint, providing an explanation for life on Earth that not only connects all creatures through the huge chunks of DNA they share but does the same for life in the great beyond. For a Disney film that works primarily as an optimistic space adventure, Mission to Mars strikingly reminded me of Terrence Malick's recent The Tree of Life, another film that used a universal canvas and the scientific conclusions of evolution to posit a spiritual connection linking all life.

This is a far cry from De Palma's usual view of humanity, where even his most loving portrayals show characters who are isolated and cut off from the world. The closest he comes to acknowledging his usual forays into underworlds and monsters is a jokey retort from Phil when Terri waxes rhapsodic on the three percent of DNA that makes humanity its own species, the three percent that gave the world Einstein and Mozart. "And Jack the Ripper," chimes Phil. Nevertheless, in Mission to Mars, we are all one, and when Jim decides to leave his empty life behind to seek meaning even deeper into the cosmos, De Palma promises to make him see just how vast the universal web of life is. It may not be De Palma's best film, but Mission to Mars is the most rapturous and hopeful of his stylistic exercises, and one of the finest displays of the love he has under all his cynicism.

Posted by

wa21955

Tuesday, September 27

Brian De Palma: Snake Eyes

Snake Eyes is, in a bizarre way, the logical continuation of Brian De Palma's previous film, Mission Impossible. Mixing political thriller with questionable plays for De Palma's capacity to capture Romantic grief, Snake Eyes likewise feels like a safe bet for the director, but one he that allows him to push his luck. If it's one of the emptiest films of De Palma's corpus—a collection of work that houses more than a few technical exercises—at least the director gives us a story so ridiculous you almost don't mind when it collapses in the third act.