It's just as well that War of the Worlds was hobbled upon its initial release by the lingering effects of Tom Cruise's infamous couch-jumping whatever. If Americans were going to let a stupid thing like that distract them, who knows how they might have reacted if they realized what all the movie had to say about 9/11 and the still-raging debate over Iraq. Even the conclusion of H.G. Wells' original novel, forecast in the opening credits expanding outward from single-cell organisms to humanity and even the cosmos, reflects the pitfalls of the War on Terror. "Occupations always fail!" declares a mad character late in the film, and one gets the distinct feeling he isn't just talking about invaders from Mars.

But War of the Worlds is, for the most part, not a commentary on the War on Terror so much as snapshot of what inspired it and how the national emotions of panic, grief, rage and bewilderment contributed to it. There's no criticism here; that would come with Spielberg's other 2005 film. No, War of the Worlds' primary aim is still to function as a blockbuster, but in its finely detailed, occasionally surreal construction is an almost therapeutic attempt to recreate an event fresh in the nation's mind, all the better to study it and to (hopefully) make a more informed decision than we did when that day actually happened.

Though Catch Me If You Can served as the non plus ultra of Spielberg's pet themes of absent fathers and confused children, War of the Worlds finds a new angle from which to approach that well-explored subject matter. Cruise may have sent the marketing department up the wall before it was all over, but his was an inspired casting choice. Spielberg presents the actor, then still America's everyman, as not merely a neglectful dad but a willfully repellent one. Cruise's Ray arrives home from work to find that he's late for picking up his kids from his ex-wife (Miranda Otto), and he offers no apology for his misunderstanding of their meeting time. Alone with the teenaged Robbie (Justin Chatwin) and young Rachel (Dakota Fanning), Ray proves to be uninterested in his children and almost willfully unconcerned with their lives and well-being.

In these opening scenes, Cruise is nearly at his most unpleasant, surpassed only by his misogynistic event speaker in Magnolia. In a hopelessly outdated and transparently thin attempt to interact with Robbie, Ray makes his son come out for a game of catch. The contentious lines they exchange slowly increase the force of each throw, until Robbie makes the mistake of mentioning him mom's new husband. Cruise's face doesn't change, but he throws the baseball so hard that one doesn't need to hear the resulting thud of the ball hitting Robbie's mitt or see the boy wince to feel the oomph behind the toss. Ray spares but a modicum more affection for Rachel, snottily reacting to her ordering takeout from a health food place and largely ignoring her.

By presenting Ray as such an unlikable figure at the start, Spielberg emphasizes that what is about to happen can affect anyone, and also that it can profoundly change people. The director forecasts the oncoming horror in ways that should be obvious to everyone: news reports bring updates of strange storms in other countries that trigger EMP blackouts, rendering whole areas without electronics. But that is the rest of the world, and no television that shows these reports stays on for very long before someone changes the channel or turns off the set. And when one of those storms forms over New York, Ray observes that the wind is blowing toward the storm clouds with a tone of mild curiosity. Even when lightning rains down on the area (without accompanying thunder), he and others continue to mill about to see what is going on. Naïve and sheltered, the Americans congregate around an opened crack in the ground, totally unperturbed until the ground begins to quake and splinter, and finally cave into a giant hole.

The next hour and 45 minutes display Spielberg at his visceral best, twisting the formal prowess he normally uses for elegant, graceful depictions of wonder and optimism into a device for conveying sheer and utter terror. From the giant hole in the ground emerges an enormous tripod, a war machine that barely has time to stretch out fully before it begins slaughtering people and destroying buildings. Ray only just manages to get away, running back to his house to grab the kids and steal a van that's been repaired after the EMP blast. As Rachel shrieks "Is it the terrorists?!" New York is reduced to embers behind them.

The connections between the alien invasion and 9/11 and the War on Terror range from the literal to the abstract. The machines, buried for however many millennia, obviously reflect underground sleeper cells, dormant until a surprise attack. Their heat rays turn people into ashes, which blanket Ray as beams cut through those around him. The image of Ray literally covered with the dead recalls horrible images of people covered in the dust and debris cloud of the falling towers, while downed airplanes and crumbling buildings only hammer home the horrid sights of that awful day.

In broader terms, the aliens elicit basic, deeply felt emotional responses. Every time a tripod happens upon Ray's location, the frame almost literally shudders with fear, while the sense of not knowing what's happening or where one might go for safety pervades every frame. There is also the anger, the instant thirst for reprisal that overrides any strategy, even sense. Robbie begins to wear a look of perpetual fury on his face, itching to strike back at the invaders despite the hopelessness of the situation. As with terrorists, the aliens are impervious to the best of our military technology: the aliens have even better technology that renders them invulnerable to attack, while the terrorists' organization makes might an irrelevant factor in the equation. Robbie represents so many people in the wake of 9/11, so ready for payback that they never stopped to consider what kind of conflict they'd be getting into, or what might happen to them when they did.

Spielberg frames all of this with surprising formalism, flecked with even more surprising traces of surrealism. After spawning an entire generation of clumsy knock-offs with the gritty, close-up handheld cameras of Saving Private Ryan, Spielberg offers a check to his legion of copycats by capturing visuals no less wrenching and instantly felt despite their careful, classical composition. Occasionally recalling the love of old genre fare that informed the Indiana Jones series, Spielberg employs some shots that have an almost storybook quality to them, as if he'd brought an illustrated copy of the book to life. One scene that particularly sticks to me takes place at a ferry as throngs of people push toward the overloaded boat, only for telltale warning signs to precede the emergence of a tripod behind everyone. As the machine lets out one of its booming horns, the camera cuts to frame it looming over the Hudson as mist swirls over the bright lights around the pier. It's a gorgeous shot, and one that freezes my heart every single time I see it.

As for the surrealism, Spielberg tops even the grim oddities of Empire of the Sun. That film included a memorable scene of Jim wandering around his ransacked neighborhood in Shanghai, abandoned luggage cast aside and clothes strewn across the ground as if their wearers had been raptured out of them. Spielberg resuses that offbeat, troubling image on a larger scale here, as tripods snatch up prey and send clothes falling gently to the ground like giant snowflakes after using up the people inside them. The director even perverts his personal use of close-ups in a shot where Rachel heads out of her brother and father's eyesight to use the bathroom by a river, only to see bodies drifting downstream. As sunlight bounces off the clear water, Spielberg pushes in on Fanning's face as the golden light flickers over her stunned features. The flicker almost gives the shot a feeling of an old silent film, and Fanning's overwhelmed shock a tinge of Expressionist horror.

There's also a shot late in the film after Ray discovers that the aliens are spreading a red weed everywhere that they fertilize with liquified humans. As he stumbles out from a hiding place, Ray walks in front of a broken wooden fence looking out into a (literally) blood-soaked horizon. It's a shot that might have come out of Johnny Guitar, a beautifully grotesque, madly stylized Western panorama as striking as it is disturbing.

Another disquieting element of War of the Worlds is the frank manner in which it suggests, like any good monster movie, that the other survivors can be as bad as the creatures. When Ray reaches the Hudson ferry, he and the kids are forcibly taken from the van by a crowd of people who want it even though there's nowhere to run. And when the tripod rises up over the ferry, the soldiers on-board instantly call for the ferry to take off, callously stranding hundreds to be massacred to make a futile attempt at getaway. But the true personification of the insanity of those left behind comes in Tim Robbins' delightfully named Harlan Ogilvy, a man who would be perfectly at home in a George A. Romero zombie film. Driven out of his mind by his family's death, Harlan shares Robbie's absurd dream of taking the fight to the aliens; armed with a shotgun, he is only infinitesimally less hopeless than the unarmed boy. As Harlan slips deeper into madness, Ray slowly realizes that he will need to deal with the man to keep Rachel safe. When the situation comes to a head, Spielberg treats us to one of his darkest shots, again staying in close-up on Rachel's face, a blindfold over her eyes and her fingers jammed in her ears as she sings a lullaby to herself, as Ray murders Harlan in the next room. Were it not for a certain scene in Munich which I will later discuss, this would be the single bleakest, most unsentimental shot in Spielberg's entire canon.

These gut-wrenching moments, combined with the technical perfection of practically every moment (Spielberg's decision to use as much live-effects as possible, as with Jurassic Park, makes the CGI that much more lastingly great) would cement War of the Worlds as one of Spielberg's greatest achievements, if not one hiccup. Yep, you guessed it, it's the ending. Spielberg retains the gist of Wells' ending for better and worse: it's fitting that he should still attribute the downfall of the invasion to bacteria against which the aliens have no immunity. It was a brilliant touch in the original novel and one that fits seamlessly here as a lesson about a technologically superior force inserting itself into an unfamiliar environment where the elements can defeat even the strongest foe.

But the other part of Wells' ending, the unlikely reunion with characters presumed dead, is harder to defend. Robbie's awkward return is simply senseless, and it robs the film of its somber implications regarding his headlong rush into death. When he leaves Ray and Rachel, he doesn't do so on the best of terms: there are things left unsaid, and the expectation of his death in the sudden conflagration spoke to all the lives cut short by that patriotic swell of enlistment and the unquestioning deployment into the Middle East. For Robbie to just show up, totally fine, at the end and allow a proper reconciliation between father and son is one of Spielberg's most glaring moments of dishonesty, denying the painful reality for a tacked-on bit of cheer that ironically seemed to piss off everyone. But with Spielberg's next release, even this tiny shred of optimism would be ruthlessly purged from all discussion of our current climate of war.

|

|

|

|

|

Home » Posts filed under Tim Robbins

Showing posts with label Tim Robbins. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Tim Robbins. Show all posts

Sunday, March 25

Wednesday, October 12

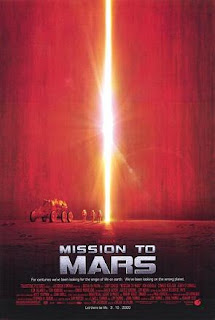

Brian De Palma: Mission to Mars

Brian De Palma's Mission to Mars is the film you'd least expect from the maker of gory, cynical deconstruction who delighted in adhering to genre tropes as much as he did tearing them apart. A PG-rated space adventure released by Disney, Mission to Mars looks on its face like the ultimate sellout move, an embrace of everything De Palma hated now that he could be trusted to make a profit off his work. Certainly critics and audiences found it easy to go with their gut; the film eked out a box office so thinly above the budget it likely falls within the margin of error, and it received scathing reviews from professionals and amateurs alike.

But I see a remarkable film, one that puts all of De Palma's generic immersion and aesthetic strength to use at the opposite end of the emotional spectrum. Here is a film so unabashedly optimistic that De Palma can open on a barbecue with red, white, and blue colors used without a drop of irony, no mean feat for man who loves his American flags huge and imperialistic. And even if one wants to play the usual simplistic game of "Who is De Palma ripping off today?" the closest you'll get is Star Wars by way of 2001. Considering that those two films stand at polar ends to each other, suggesting De Palma is just playing the plagiarist holds even less water than it always has.

That barbecue is a private party on the eve of the titular mission, as American and Russian astronauts celebrate with their families and joke with their colleagues. De Palma establishes the basic character relations through pure exposition, but there's a giddiness on the faces of Tim Robbins, Don Cheadle, Connie Nielsen and the rest that gives the stiff lines a jubilant quality. Even when Jim McConnell (Gary Sinise), the former pilot of the mission taken off assignment when his wife died, arrives, the somber tone still carries flecks of idealism and camaraderie. Cheadle's earnest condolences and reassurances cannot fully overcome how staid the dialogue is, but the look of unendurable pain on Sinise's face, an agony that simmers below his sunken eyes even—especially—when he's smiling ensures that even this trudging moment passes quickly.

But soon the action takes off, De Palma cutting to the first ship's arrival on Mars and their study of the terrain for possible colonization. Orange tinting turns the rocky landscape into a convincing duplicate of Mars, and De Palma uses his widescreen to communicate a sense of loneliness and building unease in these scenes. He also sets up the first of many tricks of perspective, pulling back from the shot of an automated rover on the surface to see its larger, human-carrying counterpart drive past and readjust the scale. Later, in space, a camera swirls outward from four astronauts floating above a flattened atmosphere to likewise reveal the true vastness of the scenario.

Yet these dwarfing visual corrections of perspective belie the intimate nature of the film itself, especially after a mysterious event destroys most of the first crew sent to Mars and prompts the other cluster of characters to fly to Luke Graham's (Cheadle) rescue. De Palma slyly cuts away from Mars just as it starts to resemble a De Palma film, with man's arrogant quest to conquer cut brutally short by a mysterious, unexplained force. By realigning with the second crew, who insist that Jim flies them despite washing out of the program, De Palma moves away from suspense and potential commentary to focus on the struggles and hopes of the team that wants to save Graham but also has six months of travel to kill.

To fill the time, De Palma stages the most joyous, effervescent shots of his career. His camera floats gracefully through space, exuberantly capturing feelings of zero gravity and also communicating an ebullient whimsy wholly absent of the director's usual sense of irony. Giddy to the point of shamelessness, these scenes recast the clinical tone of Kubrick's movement through advanced space stations as pure ecstasy. For Kubrick, the scientifically plausible technology he posited signified man's complete surrender to technology, placing man in an environment where he would literally die without his inventions helping him. But for the Romantic side of De Palma, the ability to explore space gives us the infinity to explore and the ability to leave behind troubles, or at least some of them.

In the film's finest scene, Woody (Robbins), who earlier protested the idea of dance lessons with Terri (Nielsen), puts on Van Halen's "Dance the Night Away" and twirls in zero-gravity with his wife. It's such a happy moment that everyone on-board forgets the mission and watches the two go. De Palma revels in the romance, but he also adds a tinge of sadness when Jim arrives. Sinise plays his part beautifully here, looking on with a smile that does not fade but slowly cools as he thinks of his own wife and how it so easily could have been he and Maggie dancing. It's a quiet, heartbreaking cutaway that displays De Palma's pained humanism stripped of the usual sarcasm or at least doom. That the Mars mission pairs husband and wife in the first place is itself revealing of the director's emotional approach here: in this idealized future, even scientists recognize the need for human comfort and warmth in space and want their mission leaders to be emotionally level. They just recognize that humans are emotionally level when they are happy, not clinically neutral.

All of this is not to say that Mission to Mars contains none of De Palma's darker impulses. But even they are timed to be affecting, not sinister. Consider the scene of Graham's team exploring the aberration in a Martian mountain intercut with the broadcast he and the crew recorded earlier to send back to the space station over Earth. That transmission reaches and plays for the astronauts there just as Graham and co. reach the site, and the cheeriness of the transmission (in which the crew on Mars joke and sing "Happy Birthday" to Jim) conflicts with the mounting suspense of the electronic warbling and gathering wind on Mars. The crosscutting only exacerbates the tension by making the thought of anything happening to these characters (who are all so thinly defined you know few, if any, will survive) unpleasant instead of just expected.

There's also the devastating sequence of the four members of the second mission crew forced to abandon their craft after micrometeorites lead to an engine explosion. As Woody aims for a refueling module, he secures a tether but carries too much momentum to stop, flying outside the range of his friends. Unwilling to watch her husband die, Terri cuts her own tether in a doomed attempt to rescue him, leading Woody to take drastic measures to prevent her from killing herself. His act of self-sacrifice is poignant and poetic, using tense setups—Woody propelling himself too fast, the line on the tether gun reaching its end just before it can reach him—to reach a sorrowful conclusion.

On Mars, the remaining crew reunites with a half-mad Graham, and as they wonder what it is about Mars' atmosphere that might have caused this, Jim points out that he watched his friends die and spent six months as the only man on a planet. Or is he? The storm that destroyed Graham's mission was clearly controlled, and one can only expect aliens to show up at some point. What makes Mission to Mars remarkable is how it (literally) relates those aliens to us. An earlier scene establishes a joke by having Phil (Jerry O'Connell) arrange M&Ms in zero gravity to form a DNA double-helix of what he calls his "ideal woman." Jim reaches out and nabs a few candies, asking Phil what the strand is now. "A frog?" Phil guesses after briefly studying the altered base pairs.

Amusing at that scene is, it also establishes the key theme of De Palma's film, that all life is linked to the same fundamental building blocks, with only the tiniest variations separating vastly different species. The Martians only take this idea to its endpoint, providing an explanation for life on Earth that not only connects all creatures through the huge chunks of DNA they share but does the same for life in the great beyond. For a Disney film that works primarily as an optimistic space adventure, Mission to Mars strikingly reminded me of Terrence Malick's recent The Tree of Life, another film that used a universal canvas and the scientific conclusions of evolution to posit a spiritual connection linking all life.

This is a far cry from De Palma's usual view of humanity, where even his most loving portrayals show characters who are isolated and cut off from the world. The closest he comes to acknowledging his usual forays into underworlds and monsters is a jokey retort from Phil when Terri waxes rhapsodic on the three percent of DNA that makes humanity its own species, the three percent that gave the world Einstein and Mozart. "And Jack the Ripper," chimes Phil. Nevertheless, in Mission to Mars, we are all one, and when Jim decides to leave his empty life behind to seek meaning even deeper into the cosmos, De Palma promises to make him see just how vast the universal web of life is. It may not be De Palma's best film, but Mission to Mars is the most rapturous and hopeful of his stylistic exercises, and one of the finest displays of the love he has under all his cynicism.

But I see a remarkable film, one that puts all of De Palma's generic immersion and aesthetic strength to use at the opposite end of the emotional spectrum. Here is a film so unabashedly optimistic that De Palma can open on a barbecue with red, white, and blue colors used without a drop of irony, no mean feat for man who loves his American flags huge and imperialistic. And even if one wants to play the usual simplistic game of "Who is De Palma ripping off today?" the closest you'll get is Star Wars by way of 2001. Considering that those two films stand at polar ends to each other, suggesting De Palma is just playing the plagiarist holds even less water than it always has.

That barbecue is a private party on the eve of the titular mission, as American and Russian astronauts celebrate with their families and joke with their colleagues. De Palma establishes the basic character relations through pure exposition, but there's a giddiness on the faces of Tim Robbins, Don Cheadle, Connie Nielsen and the rest that gives the stiff lines a jubilant quality. Even when Jim McConnell (Gary Sinise), the former pilot of the mission taken off assignment when his wife died, arrives, the somber tone still carries flecks of idealism and camaraderie. Cheadle's earnest condolences and reassurances cannot fully overcome how staid the dialogue is, but the look of unendurable pain on Sinise's face, an agony that simmers below his sunken eyes even—especially—when he's smiling ensures that even this trudging moment passes quickly.

But soon the action takes off, De Palma cutting to the first ship's arrival on Mars and their study of the terrain for possible colonization. Orange tinting turns the rocky landscape into a convincing duplicate of Mars, and De Palma uses his widescreen to communicate a sense of loneliness and building unease in these scenes. He also sets up the first of many tricks of perspective, pulling back from the shot of an automated rover on the surface to see its larger, human-carrying counterpart drive past and readjust the scale. Later, in space, a camera swirls outward from four astronauts floating above a flattened atmosphere to likewise reveal the true vastness of the scenario.

Yet these dwarfing visual corrections of perspective belie the intimate nature of the film itself, especially after a mysterious event destroys most of the first crew sent to Mars and prompts the other cluster of characters to fly to Luke Graham's (Cheadle) rescue. De Palma slyly cuts away from Mars just as it starts to resemble a De Palma film, with man's arrogant quest to conquer cut brutally short by a mysterious, unexplained force. By realigning with the second crew, who insist that Jim flies them despite washing out of the program, De Palma moves away from suspense and potential commentary to focus on the struggles and hopes of the team that wants to save Graham but also has six months of travel to kill.

To fill the time, De Palma stages the most joyous, effervescent shots of his career. His camera floats gracefully through space, exuberantly capturing feelings of zero gravity and also communicating an ebullient whimsy wholly absent of the director's usual sense of irony. Giddy to the point of shamelessness, these scenes recast the clinical tone of Kubrick's movement through advanced space stations as pure ecstasy. For Kubrick, the scientifically plausible technology he posited signified man's complete surrender to technology, placing man in an environment where he would literally die without his inventions helping him. But for the Romantic side of De Palma, the ability to explore space gives us the infinity to explore and the ability to leave behind troubles, or at least some of them.

In the film's finest scene, Woody (Robbins), who earlier protested the idea of dance lessons with Terri (Nielsen), puts on Van Halen's "Dance the Night Away" and twirls in zero-gravity with his wife. It's such a happy moment that everyone on-board forgets the mission and watches the two go. De Palma revels in the romance, but he also adds a tinge of sadness when Jim arrives. Sinise plays his part beautifully here, looking on with a smile that does not fade but slowly cools as he thinks of his own wife and how it so easily could have been he and Maggie dancing. It's a quiet, heartbreaking cutaway that displays De Palma's pained humanism stripped of the usual sarcasm or at least doom. That the Mars mission pairs husband and wife in the first place is itself revealing of the director's emotional approach here: in this idealized future, even scientists recognize the need for human comfort and warmth in space and want their mission leaders to be emotionally level. They just recognize that humans are emotionally level when they are happy, not clinically neutral.

All of this is not to say that Mission to Mars contains none of De Palma's darker impulses. But even they are timed to be affecting, not sinister. Consider the scene of Graham's team exploring the aberration in a Martian mountain intercut with the broadcast he and the crew recorded earlier to send back to the space station over Earth. That transmission reaches and plays for the astronauts there just as Graham and co. reach the site, and the cheeriness of the transmission (in which the crew on Mars joke and sing "Happy Birthday" to Jim) conflicts with the mounting suspense of the electronic warbling and gathering wind on Mars. The crosscutting only exacerbates the tension by making the thought of anything happening to these characters (who are all so thinly defined you know few, if any, will survive) unpleasant instead of just expected.

There's also the devastating sequence of the four members of the second mission crew forced to abandon their craft after micrometeorites lead to an engine explosion. As Woody aims for a refueling module, he secures a tether but carries too much momentum to stop, flying outside the range of his friends. Unwilling to watch her husband die, Terri cuts her own tether in a doomed attempt to rescue him, leading Woody to take drastic measures to prevent her from killing herself. His act of self-sacrifice is poignant and poetic, using tense setups—Woody propelling himself too fast, the line on the tether gun reaching its end just before it can reach him—to reach a sorrowful conclusion.

On Mars, the remaining crew reunites with a half-mad Graham, and as they wonder what it is about Mars' atmosphere that might have caused this, Jim points out that he watched his friends die and spent six months as the only man on a planet. Or is he? The storm that destroyed Graham's mission was clearly controlled, and one can only expect aliens to show up at some point. What makes Mission to Mars remarkable is how it (literally) relates those aliens to us. An earlier scene establishes a joke by having Phil (Jerry O'Connell) arrange M&Ms in zero gravity to form a DNA double-helix of what he calls his "ideal woman." Jim reaches out and nabs a few candies, asking Phil what the strand is now. "A frog?" Phil guesses after briefly studying the altered base pairs.

Amusing at that scene is, it also establishes the key theme of De Palma's film, that all life is linked to the same fundamental building blocks, with only the tiniest variations separating vastly different species. The Martians only take this idea to its endpoint, providing an explanation for life on Earth that not only connects all creatures through the huge chunks of DNA they share but does the same for life in the great beyond. For a Disney film that works primarily as an optimistic space adventure, Mission to Mars strikingly reminded me of Terrence Malick's recent The Tree of Life, another film that used a universal canvas and the scientific conclusions of evolution to posit a spiritual connection linking all life.

This is a far cry from De Palma's usual view of humanity, where even his most loving portrayals show characters who are isolated and cut off from the world. The closest he comes to acknowledging his usual forays into underworlds and monsters is a jokey retort from Phil when Terri waxes rhapsodic on the three percent of DNA that makes humanity its own species, the three percent that gave the world Einstein and Mozart. "And Jack the Ripper," chimes Phil. Nevertheless, in Mission to Mars, we are all one, and when Jim decides to leave his empty life behind to seek meaning even deeper into the cosmos, De Palma promises to make him see just how vast the universal web of life is. It may not be De Palma's best film, but Mission to Mars is the most rapturous and hopeful of his stylistic exercises, and one of the finest displays of the love he has under all his cynicism.

Posted by

wa21955

Sunday, June 19

Green Lantern (Martin Campbell, 2011)

Watching Green Lantern in 3D is like watching a glowstick through sunglasses, the already unimpressive neon goop dimmed to a murky hum of sickly light. Its dulled visual scheme matches the narrative, a story about a man chosen for the highest honor in the universe that has all the excitement of finding out one has been selected to be a Nielsen family. In fairness, this movie is not as bad as the increasingly increasingly garish X-Men: First Class, which is aging in my short-term memory like milk left out in a hot sun. Green Lantern at least lacks the pomposity and waste of recent blockbusters, but it makes up for this "shortcoming" with a stupefying lack of creativity, in a film about a hero whose power is his imagination.

Watching Green Lantern in 3D is like watching a glowstick through sunglasses, the already unimpressive neon goop dimmed to a murky hum of sickly light. Its dulled visual scheme matches the narrative, a story about a man chosen for the highest honor in the universe that has all the excitement of finding out one has been selected to be a Nielsen family. In fairness, this movie is not as bad as the increasingly increasingly garish X-Men: First Class, which is aging in my short-term memory like milk left out in a hot sun. Green Lantern at least lacks the pomposity and waste of recent blockbusters, but it makes up for this "shortcoming" with a stupefying lack of creativity, in a film about a hero whose power is his imagination.The first sign of the dearth of ideas is the hero himself. The Hal Jordan of the comics, a conservative, stoic pilot without fear, is replaced with a smarmy jackass played with much-practiced knowing by Ryan Reynolds. Jordan here is nothing more than Tom Cruise's character from Top Gun, to the point that, after he becomes the titular hero and inevitably saves the day, I expected Hal to buzz the giant lantern core on the planet Oa, making the gruff drill sergeant Kilowog (voiced by Michael Clarke Duncan, because of course he is) spill his galactic coffee all over himself in surprise and rage. But, if wishes were horses...

Green, as we are told, is the color of willpower. But it is also the color of envy, and one doesn't need 3D glasses to see DC's intent to rip off Marvel's approach to their film franchises leap off the screen. I admit to being no expert on Hal Jordan, but even a cursory look into the character reveals an overhaul to slip into Marvel's winning formula. Hal's turn to asshattery aligns him with the wisecracking Tony Stark, while his constant hand-wringing over responsibility ties him to the self-doubting Peter Parker. The decision to make the fear parasite Parallax into a giant space cloud recalls the similarly baffling treatment of Galactus. And like Thor, it introduces an expansive, intergalactic sandbox, only to spend all its time in a banal conceptualization of Earth.

The only thing Green Lantern has to distinguish itself is its loud color palette, all bright greens and yellows with splashes of magenta and fuchsia for Sinestro and Abin Sur. But of course the 3D shaves off the candy coating for the sake of a handful of scenes with any artificial depth. Martin Campbell, a more than competent action director responsible for two of the finest and most exciting Bond movies, Goldeneye and Casino Royale, cannot find the same thrill in the lava-lamp CGI of Green Lantern's hokey powers (really? A Hot Wheels track to stop an out-of control helicopter?) and the all-too-brief forays into space where the film might have worked.

Relegated mostly to Earth, Campbell has to tread through a perfunctory romance with no-nonsense/well-maybe-some-nonsense pilot/businesswoman Carol (Blake Lively) and hysterically tacked-on daddy issues for the hero and undercooked villain Hector Hammond (Peter Sarsgaard). I had to struggle not to laugh aloud at a particularly inappropriate time at the end of Hal's early flashbacks, a predictable and clumsily handled bit of tragedy to weigh upon Hal's shoulders as an attempt to explain away his incessant waffling.

The only true pleasures Green Lantern has to offer are the things it isn't: it isn't overlong like so many bloated franchise starters of late, coming in a good 20 minutes under two hours if you leave when the credits start (and who the hell will want to stay?). It is not self-serious, unlike, say, the "Born This Way" moralism of X-Men. But nothing that actually makes its way into the frame is of much use. The film tries to Marvelize Hal Jordan, but in the end he simply leaps from fool to fearless warrior without progression. But then, origin stories these days always fail to adequately build their franchises, and if Green Lantern is going to skip anything involving character growth and plot development, at least it truncates the running length to send us on our way sooner.

I'm almost impressed that a film this dull can avoid feeling longer than it is. But for the love of God, when is someone going to make one of these epic films with even a hint of wonder? They're superheroes, for the love of Pete; awe is what they do best. But there isn't a single moment of Green Lantern that attempts to capture the overwhelming feeling of being thrust into something unfathomably vast, and I remain ever-unsettled by Hollywood's ability to rob the universe of its grandeur. DC heroes typically lack the psychological depth of their Marvel counterparts, but an insightful film could have been made about Hal's stubbornness and two-dimensional commitment to duty. In trying to ape Marvel, Campbell and the DC team overseeing him have ironically only simplified this character further.

Posted by

wa21955

Labels:

2011,

Blake Lively,

Geoffrey Rush,

Mark Strong,

Martin Campbell,

Michael Clarke Duncan,

Peter Sarsgaard,

Ryan Reynolds,

Tim Robbins