Terri feels like the film the Duplass brothers' intended crossover Cyrus wanted to be, even if its subject matter is different and the overall quality of the two movies is not radically different. Azazel Jacobs' smooth, crisp, measured direction lingers on the odd but believable high-school world crafted by screenwriter Patrick DeWitt, drawing out its beats until "comedy" and "drama" become meaningless distinctions. This is not discomfort humor, or at least not in the sense of squirm comedy. Rather, Terri ekes comedy out of the discomfort of life itself, not the embarrassing shenanigans of warped loonies who may well exist but are not as common as the quiet embarrassments and indignities on display here.

The titular protagonist (Jacob Wysocki) is an overweight 15-year-old who lives with his uncle, James (The Office's Creed Bratton), a loving but often removed man in the early stages of dementia. Picked on at school and made increasingly lonely by the mental slippage of the only person who speaks to him, Terri starts showing up late for class and constantly wears pajamas, only further distancing himself from the other kids. Taller and wider than everyone else, mocked for his poverty and weight, and decked out in clothes that isolate him in the frame, Terri looks absurd, but the look of muted loneliness on his face evokes a great deal of pain.

Orbiting around Terri is a cast of skittish but lethargic oddballs who behave like your average zany high-school-movie kids after passing around bottles of Adderall. Terri worries about fitting in among the slimmer boys who boast of sexual conquests, but their cagey, pubescent jitters make them no more normal or centered than Terri. One boy even coaxes a girl (whom Terri likes) to let him grope her during a class But the isolation is taking its toll: forced into setting traps for mice by his uncle, Terri's initial reluctance turns to a brief fascination with death that signals how slowly but surely he is headed for the edge.

Noticing this is the school's assistant principal, Mr. Fitzgerald (John C. Reilly), who decides to take Terri under his wing in a seeming act of kindness. Reilly plays Fitzgerald as the picked-on kid who overcame his shyness and sense of hurt only through completely internalizing child therapist exercises. He talks like a motivational speaker in search of a gymnasium, trying to pep up Terri with personal experience he's honed into slogans so pat he could deliver them in call-and-response cheers.

Fitzgerald makes plain a truth that links the characters of Terri: everyone wants something from the others. Heather's (Olivia Crocicchia) boyfriend wants sex from her, and Terri at least wants some kind of recognition from her. Uncle James wants Terri around to do all the chores he cannot. A spiky basket of pent-up sexual aggression named Chad hangs out with Terri for a time, but he really gravitates toward the protagonist when his kindness wins Heather over and presents an opportunity for the gangly kid to swoop in and steal her from the fat guy. The nicest of these characters—Terri, Fitzgerald, and Heather—all carry such baggage that even their niceness seems suspect at times, or at least driven by their own desire to be validated by someone else. As Heather quietly, morosely yet defiantly explains her willingness to let her ex- touch her in class, sometimes it's just nice to be wanted.

The understanding that wanting something from others is not only not inherently evil but natural softens what might have been a cynical look at the nastiness and exploitative relations of children and adults. Jacobs wrings comedy out of downbeat moments, such as a funeral for Fitzgerald's old secretary that makes Eleanor Rigby's seem a New Orleans jazz wake in comparison, but he does not sacrifice the chill of such scenes. The film climaxes with a date of sorts between Terri and Heather back at Uncle James' place, a date into which Chad wedges himself, and the bored, awkward chatter leads to booze and pills that tilt the sequence slowly off its axis. Chad's drunken, predatory lures are as creepy as they are hilarious, while Terri wrestles with his temptation in heartbreaking bewilderment in a moment that shows considerable maturity in displaying the moral weight of potentially acting on urges with someone too drunk to give proper consent. We've certainly come a long way from Animal House downright mocking a character's masculinity for not date-raping an underage girl.

Terri's minute observations of real human emotions elevate some of the shakier elements of inconsistency and insecurity, issues easily dismissed as minor. In one brief but memorable exchange, a deluded Uncle James grabs Heather and sweetly but pointedly speaks beyond her, "There's no use in pretending you're thinking of anybody but yourself." That idea of self-serving consideration runs through the film, but as we see when Terri faces his hardest challenge of moral fiber, genuine decency does exist here. For a film so stark that its laughs often die before they even reach the throat, Terri also proved unexpectedly moving, its understated conclusion one of the more hopeful of the year. Slight quibbles with some repetition aside, this is a fine work of deadpan comedy and revealing insight.

|

|

|

|

|

Home » All posts

Friday, October 14

Kick-Ass: Story Writing - Narratives

This film has some scenes which show violence, and I would never recommend them for the EFL/ESL classes. This scene, though, does not, and it is great for story telling/ narrative writing. In fact, it is a very attractive segment. Make sure your audience consists of adults.

I. Watch the movie segments with sounds off. Pay attention to the strips so you can come

up with the story itself. If necessary, watch it twice with sounds off.

up with the story itself. If necessary, watch it twice with sounds off.

II. Work in pairs. Write down a story for the strips. Use your imagination and be creative.

III. Read your stories out loud.

IV. Watch the segments with sounds on now. Compare your stories. Which group wrote the closest ideas to what was shown in the segment.

V. Role play the story.

MOVIE SEGMENT DOWNLOAD - KICK ASS

THERE IS NOT A WORKSHEET FOR THIS ACTIVITY BECAUSE IT IS NOT NECESSARY

Wednesday, October 12

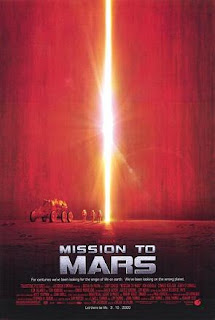

Brian De Palma: Mission to Mars

Brian De Palma's Mission to Mars is the film you'd least expect from the maker of gory, cynical deconstruction who delighted in adhering to genre tropes as much as he did tearing them apart. A PG-rated space adventure released by Disney, Mission to Mars looks on its face like the ultimate sellout move, an embrace of everything De Palma hated now that he could be trusted to make a profit off his work. Certainly critics and audiences found it easy to go with their gut; the film eked out a box office so thinly above the budget it likely falls within the margin of error, and it received scathing reviews from professionals and amateurs alike.

But I see a remarkable film, one that puts all of De Palma's generic immersion and aesthetic strength to use at the opposite end of the emotional spectrum. Here is a film so unabashedly optimistic that De Palma can open on a barbecue with red, white, and blue colors used without a drop of irony, no mean feat for man who loves his American flags huge and imperialistic. And even if one wants to play the usual simplistic game of "Who is De Palma ripping off today?" the closest you'll get is Star Wars by way of 2001. Considering that those two films stand at polar ends to each other, suggesting De Palma is just playing the plagiarist holds even less water than it always has.

That barbecue is a private party on the eve of the titular mission, as American and Russian astronauts celebrate with their families and joke with their colleagues. De Palma establishes the basic character relations through pure exposition, but there's a giddiness on the faces of Tim Robbins, Don Cheadle, Connie Nielsen and the rest that gives the stiff lines a jubilant quality. Even when Jim McConnell (Gary Sinise), the former pilot of the mission taken off assignment when his wife died, arrives, the somber tone still carries flecks of idealism and camaraderie. Cheadle's earnest condolences and reassurances cannot fully overcome how staid the dialogue is, but the look of unendurable pain on Sinise's face, an agony that simmers below his sunken eyes even—especially—when he's smiling ensures that even this trudging moment passes quickly.

But soon the action takes off, De Palma cutting to the first ship's arrival on Mars and their study of the terrain for possible colonization. Orange tinting turns the rocky landscape into a convincing duplicate of Mars, and De Palma uses his widescreen to communicate a sense of loneliness and building unease in these scenes. He also sets up the first of many tricks of perspective, pulling back from the shot of an automated rover on the surface to see its larger, human-carrying counterpart drive past and readjust the scale. Later, in space, a camera swirls outward from four astronauts floating above a flattened atmosphere to likewise reveal the true vastness of the scenario.

Yet these dwarfing visual corrections of perspective belie the intimate nature of the film itself, especially after a mysterious event destroys most of the first crew sent to Mars and prompts the other cluster of characters to fly to Luke Graham's (Cheadle) rescue. De Palma slyly cuts away from Mars just as it starts to resemble a De Palma film, with man's arrogant quest to conquer cut brutally short by a mysterious, unexplained force. By realigning with the second crew, who insist that Jim flies them despite washing out of the program, De Palma moves away from suspense and potential commentary to focus on the struggles and hopes of the team that wants to save Graham but also has six months of travel to kill.

To fill the time, De Palma stages the most joyous, effervescent shots of his career. His camera floats gracefully through space, exuberantly capturing feelings of zero gravity and also communicating an ebullient whimsy wholly absent of the director's usual sense of irony. Giddy to the point of shamelessness, these scenes recast the clinical tone of Kubrick's movement through advanced space stations as pure ecstasy. For Kubrick, the scientifically plausible technology he posited signified man's complete surrender to technology, placing man in an environment where he would literally die without his inventions helping him. But for the Romantic side of De Palma, the ability to explore space gives us the infinity to explore and the ability to leave behind troubles, or at least some of them.

In the film's finest scene, Woody (Robbins), who earlier protested the idea of dance lessons with Terri (Nielsen), puts on Van Halen's "Dance the Night Away" and twirls in zero-gravity with his wife. It's such a happy moment that everyone on-board forgets the mission and watches the two go. De Palma revels in the romance, but he also adds a tinge of sadness when Jim arrives. Sinise plays his part beautifully here, looking on with a smile that does not fade but slowly cools as he thinks of his own wife and how it so easily could have been he and Maggie dancing. It's a quiet, heartbreaking cutaway that displays De Palma's pained humanism stripped of the usual sarcasm or at least doom. That the Mars mission pairs husband and wife in the first place is itself revealing of the director's emotional approach here: in this idealized future, even scientists recognize the need for human comfort and warmth in space and want their mission leaders to be emotionally level. They just recognize that humans are emotionally level when they are happy, not clinically neutral.

All of this is not to say that Mission to Mars contains none of De Palma's darker impulses. But even they are timed to be affecting, not sinister. Consider the scene of Graham's team exploring the aberration in a Martian mountain intercut with the broadcast he and the crew recorded earlier to send back to the space station over Earth. That transmission reaches and plays for the astronauts there just as Graham and co. reach the site, and the cheeriness of the transmission (in which the crew on Mars joke and sing "Happy Birthday" to Jim) conflicts with the mounting suspense of the electronic warbling and gathering wind on Mars. The crosscutting only exacerbates the tension by making the thought of anything happening to these characters (who are all so thinly defined you know few, if any, will survive) unpleasant instead of just expected.

There's also the devastating sequence of the four members of the second mission crew forced to abandon their craft after micrometeorites lead to an engine explosion. As Woody aims for a refueling module, he secures a tether but carries too much momentum to stop, flying outside the range of his friends. Unwilling to watch her husband die, Terri cuts her own tether in a doomed attempt to rescue him, leading Woody to take drastic measures to prevent her from killing herself. His act of self-sacrifice is poignant and poetic, using tense setups—Woody propelling himself too fast, the line on the tether gun reaching its end just before it can reach him—to reach a sorrowful conclusion.

On Mars, the remaining crew reunites with a half-mad Graham, and as they wonder what it is about Mars' atmosphere that might have caused this, Jim points out that he watched his friends die and spent six months as the only man on a planet. Or is he? The storm that destroyed Graham's mission was clearly controlled, and one can only expect aliens to show up at some point. What makes Mission to Mars remarkable is how it (literally) relates those aliens to us. An earlier scene establishes a joke by having Phil (Jerry O'Connell) arrange M&Ms in zero gravity to form a DNA double-helix of what he calls his "ideal woman." Jim reaches out and nabs a few candies, asking Phil what the strand is now. "A frog?" Phil guesses after briefly studying the altered base pairs.

Amusing at that scene is, it also establishes the key theme of De Palma's film, that all life is linked to the same fundamental building blocks, with only the tiniest variations separating vastly different species. The Martians only take this idea to its endpoint, providing an explanation for life on Earth that not only connects all creatures through the huge chunks of DNA they share but does the same for life in the great beyond. For a Disney film that works primarily as an optimistic space adventure, Mission to Mars strikingly reminded me of Terrence Malick's recent The Tree of Life, another film that used a universal canvas and the scientific conclusions of evolution to posit a spiritual connection linking all life.

This is a far cry from De Palma's usual view of humanity, where even his most loving portrayals show characters who are isolated and cut off from the world. The closest he comes to acknowledging his usual forays into underworlds and monsters is a jokey retort from Phil when Terri waxes rhapsodic on the three percent of DNA that makes humanity its own species, the three percent that gave the world Einstein and Mozart. "And Jack the Ripper," chimes Phil. Nevertheless, in Mission to Mars, we are all one, and when Jim decides to leave his empty life behind to seek meaning even deeper into the cosmos, De Palma promises to make him see just how vast the universal web of life is. It may not be De Palma's best film, but Mission to Mars is the most rapturous and hopeful of his stylistic exercises, and one of the finest displays of the love he has under all his cynicism.

But I see a remarkable film, one that puts all of De Palma's generic immersion and aesthetic strength to use at the opposite end of the emotional spectrum. Here is a film so unabashedly optimistic that De Palma can open on a barbecue with red, white, and blue colors used without a drop of irony, no mean feat for man who loves his American flags huge and imperialistic. And even if one wants to play the usual simplistic game of "Who is De Palma ripping off today?" the closest you'll get is Star Wars by way of 2001. Considering that those two films stand at polar ends to each other, suggesting De Palma is just playing the plagiarist holds even less water than it always has.

That barbecue is a private party on the eve of the titular mission, as American and Russian astronauts celebrate with their families and joke with their colleagues. De Palma establishes the basic character relations through pure exposition, but there's a giddiness on the faces of Tim Robbins, Don Cheadle, Connie Nielsen and the rest that gives the stiff lines a jubilant quality. Even when Jim McConnell (Gary Sinise), the former pilot of the mission taken off assignment when his wife died, arrives, the somber tone still carries flecks of idealism and camaraderie. Cheadle's earnest condolences and reassurances cannot fully overcome how staid the dialogue is, but the look of unendurable pain on Sinise's face, an agony that simmers below his sunken eyes even—especially—when he's smiling ensures that even this trudging moment passes quickly.

But soon the action takes off, De Palma cutting to the first ship's arrival on Mars and their study of the terrain for possible colonization. Orange tinting turns the rocky landscape into a convincing duplicate of Mars, and De Palma uses his widescreen to communicate a sense of loneliness and building unease in these scenes. He also sets up the first of many tricks of perspective, pulling back from the shot of an automated rover on the surface to see its larger, human-carrying counterpart drive past and readjust the scale. Later, in space, a camera swirls outward from four astronauts floating above a flattened atmosphere to likewise reveal the true vastness of the scenario.

Yet these dwarfing visual corrections of perspective belie the intimate nature of the film itself, especially after a mysterious event destroys most of the first crew sent to Mars and prompts the other cluster of characters to fly to Luke Graham's (Cheadle) rescue. De Palma slyly cuts away from Mars just as it starts to resemble a De Palma film, with man's arrogant quest to conquer cut brutally short by a mysterious, unexplained force. By realigning with the second crew, who insist that Jim flies them despite washing out of the program, De Palma moves away from suspense and potential commentary to focus on the struggles and hopes of the team that wants to save Graham but also has six months of travel to kill.

To fill the time, De Palma stages the most joyous, effervescent shots of his career. His camera floats gracefully through space, exuberantly capturing feelings of zero gravity and also communicating an ebullient whimsy wholly absent of the director's usual sense of irony. Giddy to the point of shamelessness, these scenes recast the clinical tone of Kubrick's movement through advanced space stations as pure ecstasy. For Kubrick, the scientifically plausible technology he posited signified man's complete surrender to technology, placing man in an environment where he would literally die without his inventions helping him. But for the Romantic side of De Palma, the ability to explore space gives us the infinity to explore and the ability to leave behind troubles, or at least some of them.

In the film's finest scene, Woody (Robbins), who earlier protested the idea of dance lessons with Terri (Nielsen), puts on Van Halen's "Dance the Night Away" and twirls in zero-gravity with his wife. It's such a happy moment that everyone on-board forgets the mission and watches the two go. De Palma revels in the romance, but he also adds a tinge of sadness when Jim arrives. Sinise plays his part beautifully here, looking on with a smile that does not fade but slowly cools as he thinks of his own wife and how it so easily could have been he and Maggie dancing. It's a quiet, heartbreaking cutaway that displays De Palma's pained humanism stripped of the usual sarcasm or at least doom. That the Mars mission pairs husband and wife in the first place is itself revealing of the director's emotional approach here: in this idealized future, even scientists recognize the need for human comfort and warmth in space and want their mission leaders to be emotionally level. They just recognize that humans are emotionally level when they are happy, not clinically neutral.

All of this is not to say that Mission to Mars contains none of De Palma's darker impulses. But even they are timed to be affecting, not sinister. Consider the scene of Graham's team exploring the aberration in a Martian mountain intercut with the broadcast he and the crew recorded earlier to send back to the space station over Earth. That transmission reaches and plays for the astronauts there just as Graham and co. reach the site, and the cheeriness of the transmission (in which the crew on Mars joke and sing "Happy Birthday" to Jim) conflicts with the mounting suspense of the electronic warbling and gathering wind on Mars. The crosscutting only exacerbates the tension by making the thought of anything happening to these characters (who are all so thinly defined you know few, if any, will survive) unpleasant instead of just expected.

There's also the devastating sequence of the four members of the second mission crew forced to abandon their craft after micrometeorites lead to an engine explosion. As Woody aims for a refueling module, he secures a tether but carries too much momentum to stop, flying outside the range of his friends. Unwilling to watch her husband die, Terri cuts her own tether in a doomed attempt to rescue him, leading Woody to take drastic measures to prevent her from killing herself. His act of self-sacrifice is poignant and poetic, using tense setups—Woody propelling himself too fast, the line on the tether gun reaching its end just before it can reach him—to reach a sorrowful conclusion.

On Mars, the remaining crew reunites with a half-mad Graham, and as they wonder what it is about Mars' atmosphere that might have caused this, Jim points out that he watched his friends die and spent six months as the only man on a planet. Or is he? The storm that destroyed Graham's mission was clearly controlled, and one can only expect aliens to show up at some point. What makes Mission to Mars remarkable is how it (literally) relates those aliens to us. An earlier scene establishes a joke by having Phil (Jerry O'Connell) arrange M&Ms in zero gravity to form a DNA double-helix of what he calls his "ideal woman." Jim reaches out and nabs a few candies, asking Phil what the strand is now. "A frog?" Phil guesses after briefly studying the altered base pairs.

Amusing at that scene is, it also establishes the key theme of De Palma's film, that all life is linked to the same fundamental building blocks, with only the tiniest variations separating vastly different species. The Martians only take this idea to its endpoint, providing an explanation for life on Earth that not only connects all creatures through the huge chunks of DNA they share but does the same for life in the great beyond. For a Disney film that works primarily as an optimistic space adventure, Mission to Mars strikingly reminded me of Terrence Malick's recent The Tree of Life, another film that used a universal canvas and the scientific conclusions of evolution to posit a spiritual connection linking all life.

This is a far cry from De Palma's usual view of humanity, where even his most loving portrayals show characters who are isolated and cut off from the world. The closest he comes to acknowledging his usual forays into underworlds and monsters is a jokey retort from Phil when Terri waxes rhapsodic on the three percent of DNA that makes humanity its own species, the three percent that gave the world Einstein and Mozart. "And Jack the Ripper," chimes Phil. Nevertheless, in Mission to Mars, we are all one, and when Jim decides to leave his empty life behind to seek meaning even deeper into the cosmos, De Palma promises to make him see just how vast the universal web of life is. It may not be De Palma's best film, but Mission to Mars is the most rapturous and hopeful of his stylistic exercises, and one of the finest displays of the love he has under all his cynicism.

Posted by

wa21955

Monday, October 10

Jane Eyre (Cary Fukunaga, 2011)

Cary Fukunaga displays such an immediate grasp of the Gothic tones of Charlotte Brontë's eerie, macabre romance that the speed with which he loses his grip upon them is all the more frustrating. Whenever his camera follows the protagonist outdoors, or into the dimmest, grimiest recesses of Rochester's home, Jane Eyre overflows with atmosphere. Its cold, flora-less English countrysides and purulent candlelit interiors capture the darker moods of Brontë's novel better than any of the few adaptations I've seen.

The romance is another story. Brontë's Jane Eyre puts forth a disturbingly insular love affair between two lonely pariahs. It's one of the most passionate books I've ever read, yet almost as off-putting in its unchecked desires as a Twilight novel. Jane and Rochester become obsessed with each other because they have no one else in the world, stewing in their lust and pain and terrifying joy in their private heaven and hell. Fukunaga's film communicates practically none of this dangerous level of attraction, omitting the novel's most perilous demonstrations of twisted, isolated love and softening what remains. Beginning with such perfect solemnity, Jane Eyre soon turns into a listless period drama not even livened by the raving embodiment of uninhibited female sexuality living in the attic.

But before the film even gets to Jane and Rochester's romance, it first does its damnedest to strip away dramatic tension with its errant timeline jumps, an error egregious for sapping the brilliant scenes of Jane's youth. These childhood scenes boil down the eeriness, terror, and crippling insurmountable oppression of Jane's abuse by relatives and schoolmasters to their despairing essence. Fukunaga makes even the doomed friendship between Jane and Helen more palpably devastating in this manner, reducing their screentime together to essentially meeting and Helen's last night alive. As they say, it's better to have loved and lost than to have never loved at all, and this Jane does not even get to enjoy a brief respite of companionship.

The childhood scenes also capture that peculiar blend of strength and frailty in the girl that Mia Wasikowska flawlessly portrays as the adult Jane. Thin and pale, Wasikowska looks as if she won't even make it past the opening, pre-flashback shots stumbling around the foggy, bleak countryside with only her ragged, panting breath for a soundtrack. But her slight frame also reveals so much bone structure that that which is visible on her is sharp, angular and hardened. Rochester finds himself attracted to Jane as much for her pointed directness as her kindness, and the actress exudes forthright immediacy in every gesture.

Wasikowska is the saving grace of the film, offering a masterclass in acting far beyond her years. She knows how to position herself in every shot for maximum effect, either to assert a strength that never ceases to surprise or a vulnerability that cannot shatter her adamantine will but can bring her to the verge of collapse. It's a performance so minutely controlled that you can turn the sound off and not miss anything Jane communicates throughout the film. And Wasikowska does this within the stiff-upper-lip confines of period-style acting, her gestures never huge but unfurling huge swaths of pain, desire, and sorrow.

If only she clicked with Rochester. Michael Fassbender has quickly and justifiably emerged as one of the finest actors of his generation, but his Rochester is curiously inert. Though vague tendrils of lust wrap around his eyes when he first converses/engages in a verbal sparring match with Jane, Fassbender never properly communicates the crippling desire Rochester feels for Jane. Part of this isn't his fault—Fukunaga and screenwriter Moira Buffini strip away his most desperate actions, especially the darkly hysterical setpiece of him dressing up as a gypsy fortuneteller to drive away his ostensible fiancée and test Jane—giving him almost nothing to do past the 45-minute mark. Fassbender beautifully renders Rochester's boorishness, but that side of Rochester fades quickly to be replaced, in theory, by the lovesick man incapable of taming himself. In practice, however, Fassbender soon has little to do save brood, reducing Rochester's terrifying intemperance to the Edward Cullen-esque passionate dispassion that (very) indirectly grew out of Rochester in the first place.

For a fleeting moment I thought Jane Eyre would be one of the finest literary adaptations in recent memory, Fukunaga's gifted direction generating gulfs of mood out of his wordless opening shots and Wasikowska's pitch-perfect performance nailing Jane even when the script fails to understand the character. Sadly, its temporal bouncing and too-stripped narrative lose focus and attention before the film moves past its first act. Neither a great film nor even a particularly good one, Jane Eyre nevertheless flirts so boldly with greatness that its failure to live up to its own ambition merely disappoints. And I'd gladly watch it again to see Wasikowska blow away a decade's worth of corseted Keira Knightley gigs in one shot.

The romance is another story. Brontë's Jane Eyre puts forth a disturbingly insular love affair between two lonely pariahs. It's one of the most passionate books I've ever read, yet almost as off-putting in its unchecked desires as a Twilight novel. Jane and Rochester become obsessed with each other because they have no one else in the world, stewing in their lust and pain and terrifying joy in their private heaven and hell. Fukunaga's film communicates practically none of this dangerous level of attraction, omitting the novel's most perilous demonstrations of twisted, isolated love and softening what remains. Beginning with such perfect solemnity, Jane Eyre soon turns into a listless period drama not even livened by the raving embodiment of uninhibited female sexuality living in the attic.

But before the film even gets to Jane and Rochester's romance, it first does its damnedest to strip away dramatic tension with its errant timeline jumps, an error egregious for sapping the brilliant scenes of Jane's youth. These childhood scenes boil down the eeriness, terror, and crippling insurmountable oppression of Jane's abuse by relatives and schoolmasters to their despairing essence. Fukunaga makes even the doomed friendship between Jane and Helen more palpably devastating in this manner, reducing their screentime together to essentially meeting and Helen's last night alive. As they say, it's better to have loved and lost than to have never loved at all, and this Jane does not even get to enjoy a brief respite of companionship.

The childhood scenes also capture that peculiar blend of strength and frailty in the girl that Mia Wasikowska flawlessly portrays as the adult Jane. Thin and pale, Wasikowska looks as if she won't even make it past the opening, pre-flashback shots stumbling around the foggy, bleak countryside with only her ragged, panting breath for a soundtrack. But her slight frame also reveals so much bone structure that that which is visible on her is sharp, angular and hardened. Rochester finds himself attracted to Jane as much for her pointed directness as her kindness, and the actress exudes forthright immediacy in every gesture.

Wasikowska is the saving grace of the film, offering a masterclass in acting far beyond her years. She knows how to position herself in every shot for maximum effect, either to assert a strength that never ceases to surprise or a vulnerability that cannot shatter her adamantine will but can bring her to the verge of collapse. It's a performance so minutely controlled that you can turn the sound off and not miss anything Jane communicates throughout the film. And Wasikowska does this within the stiff-upper-lip confines of period-style acting, her gestures never huge but unfurling huge swaths of pain, desire, and sorrow.

If only she clicked with Rochester. Michael Fassbender has quickly and justifiably emerged as one of the finest actors of his generation, but his Rochester is curiously inert. Though vague tendrils of lust wrap around his eyes when he first converses/engages in a verbal sparring match with Jane, Fassbender never properly communicates the crippling desire Rochester feels for Jane. Part of this isn't his fault—Fukunaga and screenwriter Moira Buffini strip away his most desperate actions, especially the darkly hysterical setpiece of him dressing up as a gypsy fortuneteller to drive away his ostensible fiancée and test Jane—giving him almost nothing to do past the 45-minute mark. Fassbender beautifully renders Rochester's boorishness, but that side of Rochester fades quickly to be replaced, in theory, by the lovesick man incapable of taming himself. In practice, however, Fassbender soon has little to do save brood, reducing Rochester's terrifying intemperance to the Edward Cullen-esque passionate dispassion that (very) indirectly grew out of Rochester in the first place.

For a fleeting moment I thought Jane Eyre would be one of the finest literary adaptations in recent memory, Fukunaga's gifted direction generating gulfs of mood out of his wordless opening shots and Wasikowska's pitch-perfect performance nailing Jane even when the script fails to understand the character. Sadly, its temporal bouncing and too-stripped narrative lose focus and attention before the film moves past its first act. Neither a great film nor even a particularly good one, Jane Eyre nevertheless flirts so boldly with greatness that its failure to live up to its own ambition merely disappoints. And I'd gladly watch it again to see Wasikowska blow away a decade's worth of corseted Keira Knightley gigs in one shot.

Sunday, October 9

The Ides of March (George Clooney, 2011)

The Ides of March is a political drama under the mistaken belief it's a thriller. It film hinges on a Shocking Revelation telegraphed in the first five minutes, the fallout of which wishes to throw the audience for a loop but instead unfolds in tedious predictability. Its title, which connotes portentous imagery of politics at its nastiest, fails to capture the true mood of the film. There is no sense of doom hanging over George Clooney's film, only a sad resignation. A more accurate, and no less political, title would have been CNN's perennial sign off, "We'll Have to Leave It There." In an attempt to ensure wide box office appeal, Clooney's film waters down its rhetoric and potential depth of savagery behind the scenes to come to the banal, universal truth that politics corrupts people, a maxim accepted at face value and not explored to any extent.

As such, The Ides of March embodies the same neutered centrism we see in our current president. Clooney plays his presidential candidate as the Obama of 2008 but with even more broad appeal. He's got military experience, leadership experience, and all the talking points that made Obama a symbol of change. But in breaking the clay feet of this alloyed idol, Clooney tries so hard to blame the idea of politics in general, of that commonly accepted evil, that he fatally undermines any possible belief the audience could have in the idealistic innocence of its politics-savvy protagonist.

That politico would be Stephen Myers (Ryan Gosling), a 30-year-old whose campaign experience and acumen gives him the chops of a politician twice his age. He is ruthless, myopically focused on humans as numbers (he throws the upcoming generation under the bus since they can't vote), and arrogant, yet we're made to believe he only throws his calculating support behind causes in which he believes. But however thin that premise is, one cannot blame him for buying into Pennsylvania Gov. Mike Morris (Clooney). A hardcore, passionate liberal who also balanced his state's budget and served honorably in the military, Morris can steamroll the Republicans with ease, especially as they have no remotely viable candidate (sound familiar as we head into 2012?). Unfortunately, he has to get through the Democratic primary first, and internal politics prove far trickier and harder than the big fight.

In this aspect, The Ides of March puts forward an intelligent and engaging view of the political process, in which infighting brings out the most petty and backstabbing actions. Stephen's boss, Paul Zara (Philip Seymour Hoffman), has spent so much time in these trenches that he's grown completely paranoid, not of Republican spies but defections between Democratic sects. He has good reason to worry when the rival campaign manager, Tom Duffy (Paul Giamatti), comes by looking to steal away Stephen and his genius. Beau Willimon wrote the original play about his experiences working the Howard Dean campaign in 2004, but the fever pitch of the contest between Morris and Pullman more readily recalls the downright vicious fight for the Democratic nomination in 2008. And even though Obama's victory over McCain made history, his struggle to nab the nomination over Hillary Clinton made for far more gripping politics.

But the film barely even starts to get into this side of the game before it introduces a comely young intern named Molly (Evan Rachel Wood). With a sultry, beckoning haircut she must have skipped out on five hours of canvassing to get, Molly doesn't even fully walk into frame before you know exactly where this story is going. Wood plays Molly (who is also the daughter of the DNC chairmen, because why not) as a teenage minx, so comically seductive that Stephen's lapse in judgment is simply ridiculous. Then comes the expected revelation of Molly's connection to the main plot, and Wood turns the dial from "femme fatale" to "damsel" as Gosling moves to clean up everyone's mess, including his own.

At this point, the film breaks into three unified but distinct narratives: the issue of Molly's "problem," Morris' campaign, and Stephen's attempts to handle not just those but the ire of Paul for daring to meet with Duffy. The problem is that Clooney splits his time ineffectively, and he assumes that the Molly story and how it relates to the other characters is so stunning and dark that it exudes an atmosphere of clandestine cover-ups and intrigue. It doesn't, and Clooney's pleasing classical style only further hinders the film by using shadows in such a way as to be pretty, not eerie.

For a film about the seedy side of politics, The Ides of March lacks the true level of disgust needed to articulate its own points. Clooney and Gosling do their best to communicate a knowledge—already gained or slowly dawning—of the darkest depths to which politicians and the process as a whole can go. But neither feels it. These are not people living in the immediate aftermath of Nixon, capable of producing works so dark that even a triumphant, inspiring movie like All the President's Men feels borderline nihilistic. Clooney's just working off the frustration of partisan gridlock and internal squabbling. He's made a film about the incurable poison of politics when every frame clearly communicates that he thinks this all could work if people could just get their crap together. Then again, no wonder he thinks that when the film omits the true pitfalls of politics; how can anyone expect to talk about how twisted the election process is when money doesn't get mentioned once?

In their final exchange, Duffy warns Stephen to get out of politics before it jades him, a pointed bit of advice from someone who looks and sounds like Paul Giamatti. The film, however, suffers precisely because it stops before becoming completely cynical, stopping at the tipping point that turns an ambiguous final judgment by Stephen into a final half-measure that speaks more to the movie's cowardice than an embodiment of full-on political distrust. This kind of movie just isn't in Clooney's blood; when he stages a political fight, he needs a side to lionize as he had for Good Night, and Good Luck. The Ides of March needed a director on Tom Duffy's wavelength, not Stephen Myers'.

As such, The Ides of March embodies the same neutered centrism we see in our current president. Clooney plays his presidential candidate as the Obama of 2008 but with even more broad appeal. He's got military experience, leadership experience, and all the talking points that made Obama a symbol of change. But in breaking the clay feet of this alloyed idol, Clooney tries so hard to blame the idea of politics in general, of that commonly accepted evil, that he fatally undermines any possible belief the audience could have in the idealistic innocence of its politics-savvy protagonist.

That politico would be Stephen Myers (Ryan Gosling), a 30-year-old whose campaign experience and acumen gives him the chops of a politician twice his age. He is ruthless, myopically focused on humans as numbers (he throws the upcoming generation under the bus since they can't vote), and arrogant, yet we're made to believe he only throws his calculating support behind causes in which he believes. But however thin that premise is, one cannot blame him for buying into Pennsylvania Gov. Mike Morris (Clooney). A hardcore, passionate liberal who also balanced his state's budget and served honorably in the military, Morris can steamroll the Republicans with ease, especially as they have no remotely viable candidate (sound familiar as we head into 2012?). Unfortunately, he has to get through the Democratic primary first, and internal politics prove far trickier and harder than the big fight.

In this aspect, The Ides of March puts forward an intelligent and engaging view of the political process, in which infighting brings out the most petty and backstabbing actions. Stephen's boss, Paul Zara (Philip Seymour Hoffman), has spent so much time in these trenches that he's grown completely paranoid, not of Republican spies but defections between Democratic sects. He has good reason to worry when the rival campaign manager, Tom Duffy (Paul Giamatti), comes by looking to steal away Stephen and his genius. Beau Willimon wrote the original play about his experiences working the Howard Dean campaign in 2004, but the fever pitch of the contest between Morris and Pullman more readily recalls the downright vicious fight for the Democratic nomination in 2008. And even though Obama's victory over McCain made history, his struggle to nab the nomination over Hillary Clinton made for far more gripping politics.

But the film barely even starts to get into this side of the game before it introduces a comely young intern named Molly (Evan Rachel Wood). With a sultry, beckoning haircut she must have skipped out on five hours of canvassing to get, Molly doesn't even fully walk into frame before you know exactly where this story is going. Wood plays Molly (who is also the daughter of the DNC chairmen, because why not) as a teenage minx, so comically seductive that Stephen's lapse in judgment is simply ridiculous. Then comes the expected revelation of Molly's connection to the main plot, and Wood turns the dial from "femme fatale" to "damsel" as Gosling moves to clean up everyone's mess, including his own.

At this point, the film breaks into three unified but distinct narratives: the issue of Molly's "problem," Morris' campaign, and Stephen's attempts to handle not just those but the ire of Paul for daring to meet with Duffy. The problem is that Clooney splits his time ineffectively, and he assumes that the Molly story and how it relates to the other characters is so stunning and dark that it exudes an atmosphere of clandestine cover-ups and intrigue. It doesn't, and Clooney's pleasing classical style only further hinders the film by using shadows in such a way as to be pretty, not eerie.

For a film about the seedy side of politics, The Ides of March lacks the true level of disgust needed to articulate its own points. Clooney and Gosling do their best to communicate a knowledge—already gained or slowly dawning—of the darkest depths to which politicians and the process as a whole can go. But neither feels it. These are not people living in the immediate aftermath of Nixon, capable of producing works so dark that even a triumphant, inspiring movie like All the President's Men feels borderline nihilistic. Clooney's just working off the frustration of partisan gridlock and internal squabbling. He's made a film about the incurable poison of politics when every frame clearly communicates that he thinks this all could work if people could just get their crap together. Then again, no wonder he thinks that when the film omits the true pitfalls of politics; how can anyone expect to talk about how twisted the election process is when money doesn't get mentioned once?

In their final exchange, Duffy warns Stephen to get out of politics before it jades him, a pointed bit of advice from someone who looks and sounds like Paul Giamatti. The film, however, suffers precisely because it stops before becoming completely cynical, stopping at the tipping point that turns an ambiguous final judgment by Stephen into a final half-measure that speaks more to the movie's cowardice than an embodiment of full-on political distrust. This kind of movie just isn't in Clooney's blood; when he stages a political fight, he needs a side to lionize as he had for Good Night, and Good Luck. The Ides of March needed a director on Tom Duffy's wavelength, not Stephen Myers'.

Melancholia (Lars von Trier, 2011)

Melancholia is so honest, so bereft of its maker's seeming inability not to burden his films with at least one huge, garish, self-consciously edgy flaw, that Lars von Trier's disastrous press conference for it at Cannes now makes sense. That was just the cosmic balance reasserting itself, spilling out the usual tacky, ill-thought-out, offensive nonsense that weighs down so many of the director's half-baked screeds and cruel character studies. Here at last is a film that displays von Trier's genuine attempts to come to terms with emotions and thoughts, most of them at the darker end of the human spectrum, but without the, to cut to the chase, usual bullshit.

Few artists make openings as striking, gripping, or aesthetically distinct (not just from everyone else but the rest of the films in question) as von Trier, and his super-slow-motion montage here is one of his finest. Melancholia tantalizes with its apocalyptic, despairing imagery even as it clearly plays the film's finale up-front. This will not be a mystery of whether the Earth will die, something its title makes equally obvious. The apocalypse is coming, but neither von Trier nor his on-screen proxy can seem to care. As Justine (Kirsten Dunst) coldly asserts, "Life is only on Earth, and not for very long."

Following the oneiric opening montage, Melancholia begins properly with the absurd sight of a stretch limo trying in vain to navigate the narrow, twisting road up hilly terrain as newlywed couple (Dunst's Justine and Alexander Skarsgård's Michael) laugh and laugh. This scene is not the only funny moment of the film, but it's certainly the most cheerful one. When they arrive to their reception two hours late, the couple is met by Justine's sister Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg), her countenance so sharp and jagged it seems as if Gainsbourg's own angular frame sprung out of Claire's bourgeois outrage.

Within the castle Claire's husband, John (Keifer Sutherland), rented for the occasion, Manuel Alberto Claro's cinematography turns a jaundiced yellow, suggesting a sickly, nauseating quality that slowly comes to play out over Justine's face as she deals with the reception. Justine cannot bear her divorced parents' bickering, the cynical rudeness of her mother (Charlotte Rampling, playing a funhouse-mirror inverse of a hippie in her inappropriate garb as she spouts misanthropic condemnations for her toast), the condescending and almost predatory nature of her boss (Stellan Skarsgård), and the sheer discomfort of having everyone's eyes on her at all times.

Dunst times the fading of her smile across the whole of this first half, constantly trying to rally herself and failing as whispers of mental troubles start to swirl around her like an evening mist. As much an embodiment of the titular condition as the planet coming to destroy Earth, she moves her limbs with the speed of glacial shifts, swift only when she sees the opportunity to dart out of view until someone drags her back into the party. Dunst's face communicates a desperate attempt to put a look of cheer on her face, but everyone sees through it, especially Michael, whose kindness belies a mounting frustration that pushes his understanding to the breaking point.

Justine also notes the brightness of the star Antares as she sneaks occasional glimpses at the night sky outside the stuffy castle, and the disappearance of the light marks the end of the first half. Von Trier shifts focus in the aftermath of this ceremony to focus on Claire as she deals with Justine, now nearly catatonic, and silently frets over the reason for Antares' disappearance, the emergence of the hidden planet Melancholia. The diseased yellows of the first half morph into muted, even pallid tones of desaturated grays, browns and dim greens, the opposite of the verdant, exuberant views of nature in this year's other noteworthy attempt to dig into humanity via psychological types and universal staging, The Tree of Life.

Malick's film reveled in the spiritual and, though few seemed to recognize it, the scientific. It posited a notion of spiritual unity by way of evolution, which ties together the universe physically. But von Trier already had his fill of both religion and science in Antichrist, which crafted its "villain" out of warped dogma and provided no offsetting balance in the condescending, even patriarchal intervention of psychiatry. God is absent from Melancholia, and science exists only to miscalculate. John's assurances that the planet will pass by Earth conflict with our pre-spoiled ending, exposing his predictions, however informed, as just that.

Melancholia's approach seems to draw Justine's complete surrender out of her with its gravitational pull (or is it she who draws the planet here?). If Dunst played the woman with lethargy in the first half, here she reaches zero Kelvin. Though obviously an exaggeration, Justine's physical shutdown and eerie calm, even vaguely eager acceptance of the apocalypse piercingly captures the titular feeling. She does not sob or moan or scream; as we see in Claire, who eventually does these things, that is the result of anxiety. But Dunst portrays only the melancholy, the sense of hollow sorrow that does not even produce tears, that seems to collapse the body's systems until even going outside feels like an arduous trek. Those of us who have felt these bouts of defeat will recognize both the honesty of Dunst's endothermic performance and the absurdity of the film's scale; that kind of sadness really does feel cosmic, and one who feels it overloads emotionally and resets to zero.

Filled with beautiful imagery, Melancholia cannot strictly be called "pretty." Its symbolic framing—Melancholia hanging over Justine, the planet and the cold moon arranged above the two condition-personifying actresses—speaks only to sadness, the empty shell of woe left by Antichrist's fury. For von Trier, the only universal is death, and that knowledge leads him to neither panic nor live his last moments with joy. It only sucks the wind out of him, as Melancholia steals the Earth's atmosphere when it nears. Melancholia certainly won't tell anyone suffering from its affliction how to recover, but seeing even at grandiose, metaphorical exhibition of it with such deeply felt empathy is therapy in itself. Who knows, after screaming bloody murder with Antichrist and sighing with resignation here, maybe von Trier will cinematically dose himself into some modicum of happiness. Who am I kidding?

Few artists make openings as striking, gripping, or aesthetically distinct (not just from everyone else but the rest of the films in question) as von Trier, and his super-slow-motion montage here is one of his finest. Melancholia tantalizes with its apocalyptic, despairing imagery even as it clearly plays the film's finale up-front. This will not be a mystery of whether the Earth will die, something its title makes equally obvious. The apocalypse is coming, but neither von Trier nor his on-screen proxy can seem to care. As Justine (Kirsten Dunst) coldly asserts, "Life is only on Earth, and not for very long."

Following the oneiric opening montage, Melancholia begins properly with the absurd sight of a stretch limo trying in vain to navigate the narrow, twisting road up hilly terrain as newlywed couple (Dunst's Justine and Alexander Skarsgård's Michael) laugh and laugh. This scene is not the only funny moment of the film, but it's certainly the most cheerful one. When they arrive to their reception two hours late, the couple is met by Justine's sister Claire (Charlotte Gainsbourg), her countenance so sharp and jagged it seems as if Gainsbourg's own angular frame sprung out of Claire's bourgeois outrage.

Within the castle Claire's husband, John (Keifer Sutherland), rented for the occasion, Manuel Alberto Claro's cinematography turns a jaundiced yellow, suggesting a sickly, nauseating quality that slowly comes to play out over Justine's face as she deals with the reception. Justine cannot bear her divorced parents' bickering, the cynical rudeness of her mother (Charlotte Rampling, playing a funhouse-mirror inverse of a hippie in her inappropriate garb as she spouts misanthropic condemnations for her toast), the condescending and almost predatory nature of her boss (Stellan Skarsgård), and the sheer discomfort of having everyone's eyes on her at all times.

Dunst times the fading of her smile across the whole of this first half, constantly trying to rally herself and failing as whispers of mental troubles start to swirl around her like an evening mist. As much an embodiment of the titular condition as the planet coming to destroy Earth, she moves her limbs with the speed of glacial shifts, swift only when she sees the opportunity to dart out of view until someone drags her back into the party. Dunst's face communicates a desperate attempt to put a look of cheer on her face, but everyone sees through it, especially Michael, whose kindness belies a mounting frustration that pushes his understanding to the breaking point.

Justine also notes the brightness of the star Antares as she sneaks occasional glimpses at the night sky outside the stuffy castle, and the disappearance of the light marks the end of the first half. Von Trier shifts focus in the aftermath of this ceremony to focus on Claire as she deals with Justine, now nearly catatonic, and silently frets over the reason for Antares' disappearance, the emergence of the hidden planet Melancholia. The diseased yellows of the first half morph into muted, even pallid tones of desaturated grays, browns and dim greens, the opposite of the verdant, exuberant views of nature in this year's other noteworthy attempt to dig into humanity via psychological types and universal staging, The Tree of Life.

Malick's film reveled in the spiritual and, though few seemed to recognize it, the scientific. It posited a notion of spiritual unity by way of evolution, which ties together the universe physically. But von Trier already had his fill of both religion and science in Antichrist, which crafted its "villain" out of warped dogma and provided no offsetting balance in the condescending, even patriarchal intervention of psychiatry. God is absent from Melancholia, and science exists only to miscalculate. John's assurances that the planet will pass by Earth conflict with our pre-spoiled ending, exposing his predictions, however informed, as just that.

Melancholia's approach seems to draw Justine's complete surrender out of her with its gravitational pull (or is it she who draws the planet here?). If Dunst played the woman with lethargy in the first half, here she reaches zero Kelvin. Though obviously an exaggeration, Justine's physical shutdown and eerie calm, even vaguely eager acceptance of the apocalypse piercingly captures the titular feeling. She does not sob or moan or scream; as we see in Claire, who eventually does these things, that is the result of anxiety. But Dunst portrays only the melancholy, the sense of hollow sorrow that does not even produce tears, that seems to collapse the body's systems until even going outside feels like an arduous trek. Those of us who have felt these bouts of defeat will recognize both the honesty of Dunst's endothermic performance and the absurdity of the film's scale; that kind of sadness really does feel cosmic, and one who feels it overloads emotionally and resets to zero.

Filled with beautiful imagery, Melancholia cannot strictly be called "pretty." Its symbolic framing—Melancholia hanging over Justine, the planet and the cold moon arranged above the two condition-personifying actresses—speaks only to sadness, the empty shell of woe left by Antichrist's fury. For von Trier, the only universal is death, and that knowledge leads him to neither panic nor live his last moments with joy. It only sucks the wind out of him, as Melancholia steals the Earth's atmosphere when it nears. Melancholia certainly won't tell anyone suffering from its affliction how to recover, but seeing even at grandiose, metaphorical exhibition of it with such deeply felt empathy is therapy in itself. Who knows, after screaming bloody murder with Antichrist and sighing with resignation here, maybe von Trier will cinematically dose himself into some modicum of happiness. Who am I kidding?

Posted by

wa21955

Labels:

2011,

Alexander Skarsgard,

Charlotte Gainsbourg,

Keifer Sutherland,

Kirsten Dunst,

Lars von Trier,

Stellan Skarsgard

Saturday, October 8

The Strange Case of Angelica (Manoel de Oliveira, 2010)

[Note: I am considering this film for 2011 year-end lists as it got no major U.S. release until this year.]

My review for Portuguese master Manoel de Oliveira's latest feature, The Strange Case of Angelica, is up now at Cinelogue. A film about cinema so encompassing as to suggest its position as a swan song (never fear, the 102-year-old has two films slated to come out next year), Angelica is nevertheless too spry, playful and deliberately withholding and contradictory to even hint that the director is spent. Despite de Oliveira's static, half-theatrical/half-painterly composition and detachment and conflict of mood, I found this an absorbing work that made me tackle its unclear message and tone with enthusiasm, not frustration. Few films I've seen this year can top it.

So head over to Cinelogue now and check out my review. Comments appreciated.

My review for Portuguese master Manoel de Oliveira's latest feature, The Strange Case of Angelica, is up now at Cinelogue. A film about cinema so encompassing as to suggest its position as a swan song (never fear, the 102-year-old has two films slated to come out next year), Angelica is nevertheless too spry, playful and deliberately withholding and contradictory to even hint that the director is spent. Despite de Oliveira's static, half-theatrical/half-painterly composition and detachment and conflict of mood, I found this an absorbing work that made me tackle its unclear message and tone with enthusiasm, not frustration. Few films I've seen this year can top it.

So head over to Cinelogue now and check out my review. Comments appreciated.